Provenance

By the late 1950s or early 1960s, Cornelius C. Vermeule III and Emily T. Vermeule (Cambridge, MA); 2002, gift, Cornelius C. Vermeule III and Emily T. Vermeule to Princeton University. Fragments from two loutrophoroi—2002.167.1 and 2002.167.2 (see Entry 7)—were part of a larger collection of fragments bought in Athens by the Vermeules in the late 1950s or early 1960s (a penciled notation on the back of 2002.167.1 reads “Athens 1961”). Stored for years in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the majority of the sherds—those purchased with museum funds—were eventually given back to Greece, as it was determined that they likely had been discovered in the Sanctuary of Nymphe on the south slope of the Acropolis.

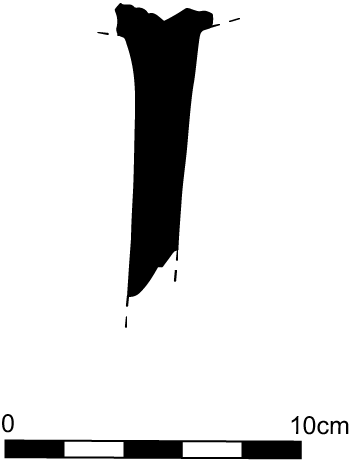

Shape and Ornament

Single fragment from the neck, with small section of offset mouth. Interior reserved. On neck above figural scene, ornamental band of checkered squares—with black dots in the center of the reserved squares—alternating with single stopt meanders.

Subject

Woman. The fragment preserves the head of a woman in profile to the right and inclined slightly downward. She wears a sakkos and an earring.

Attribution and Date

Attributed to the Washing Painter [W. L. Austin]. Circa 440–420 BCE.

Dimensions and Condition

10.1 × 6.3 cm; thickness: max. (at juncture of neck and mouth) 3.3 cm; min. (on neck) 1.6 cm. Broken on all sides. Outer surface worn and interior covered with significant incrustation. Chipping around the edges, with a large flake missing at the right, just below the meander. Much black gloss misfired a mottled reddish brown.

Bibliography

Abbreviation: Princeton RecordRecord of the Princeton University Art Museum. (1942– ). 62 (2003): 151 [not illus.].

Comparanda

The thickness and small diameter of the fragment indicate that it comes from the neck of a loutrophoros. It was initially catalogued with another loutrophoros fragment (Princeton 2002-167.2 [Entry 7]). Although loutrophoroi can have long necks that taper in thickness, the significantly greater thickness of this fragment precludes their being from the same vessel. Loutrophoroi sometimes have an ornamental band above the figural scene on the neck, usually an egg pattern, less often meanders with cross or saltire squares. The pattern on Princeton’s fragment is highly uncommon on loutrophoroi: cf. Harvard 1960.353 (CVA Baltimore, Robinson Collection 2 [USA 6], 36, pl. 49.1; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 13418). Robinson compared the Harvard loutrophoros with the Washing Painter, who often painted loutrophoroi. The figure drawing on Princeton’s fragment also resembles that of the Washing Painter, for whom see Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1126–35, 1684; Abbreviation: ParalipomenaJ. D. Beazley. Paralipomena: Additions to Attic Black-Figure Vase-Painters and to Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. Oxford, 1971 453–54, 517; Abbreviation: BAdd2Carpenter, T. H., ed. 1989. Beazley Addenda: Additional References to ABV, ARV2, and Paralipomena. 2nd ed. Oxford: Published for the British Academy by Oxford University Press. 332–33; S. Roberts, “Evidence for a Pattern in Attic Pottery Production ca. 430–350 B.C.,” Abbreviation: AJAAmerican Journal of Archaeology 77 (1973): 435–37; V. Sabetai, “The Washing Painter: A Contribution to the Wedding and Genre Iconography in the Second Half of the Fifth Century B.C.” (PhD diss., University of Cincinnati, 1993); G. Giudice, Il Tornio, la nave, le terre lontane: Ceramografi attici in Magna Grecia nella seconda metà del V sec. A.C.; Rotte e vie di distribuzione (Rome, 2007), nos. 212–22. As noted by Sabetai (“Washing Painter,” 222), the great divergence in the quality of the Washing Painter’s draftsmanship, often on the same vase, occasionally presents problems for the identification of the painter. Nevertheless, an association between Princeton’s fragment and the Washing Painter is evident, in particular in the slightly curved nostril, the downturned stroke of the mouth that lends the figure a serious expression, the rounded chin, and the pendant pupil: cf. a loutrophoros fragment formerly in an Oxford private collection (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1128.93; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 214902). The treatment of the hair above the forehead, not covered by the sakkos, is also typical of the Washing Painter: cf. the women on the neck of Houston 37.12 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1127.13; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 214894). The Washing Painter was heavily influenced by the quiet reserve of the “Parthenonian” style, which is evident on the Princeton fragment in the woman’s solemn expression and lowered downturned head.

Identification of the two types of loutrophoroi depends on the position of the handles: the hydria type has upright loop handles on either side of the shoulder and a vertical strap handle on the back; and the amphora type has strap handles on each side of the neck. It is impossible to tell to which type Princeton’s fragment belongs. For loutrophoroi, see R. Ginouvès, Balaneutikè: Recherches sur le bain dans l’antiquité grecque (Paris, 1962); Sabetai, “Washing Painter,” 129–46; id., CVA Athens, Benaki Museum 1 (Greece 9), 31–38; R. M. Mösch-Klingele, Die Loutrophóros im Hochzeits- und Begräbnisritual des 5. Jahrhunderts v. Chr. in Athen (Bern, 2006). The earliest red-figure loutrophoros has been convincingly attributed by Guy to Epiktetos: Athens, Acr. 636 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 25.1, 237, 1604; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 200142). Most red-figure examples, however, date from the second half of the fifth century. Almost all loutrophoroi with known provenances come from cemeteries and shrines in Athens and its environs, in particular the Sanctuary of the Nymphe on the southern slope of the Acropolis. The red-figure finds from the sanctuary have yet to be published, but for the site’s black-figure loutrophoroi, see C. Papadopoulou-Kanellopoulou, Ιερό της Νύμφης: Μελανόμορφες λουτροφόροι (Athens, 1997). Given the shape’s association with weddings and its use for carrying water for a bride’s prenuptial bath, such loutrophoroi were likely dedicated by brides after their weddings: see, most recently, Sabetai, “Wedding Vases of the Athenians: A View from Sanctuaries and Houses,” Abbreviation: MètisMètis: Anthropologie des mondes grecs anciens 12 (2014): 51–75. For a discussion of loutrophoroi in funerary contexts, perhaps connected with the graves of unmarried dead, see J. Bergemann, “Die sogennante Loutrophoros: Grabmal für unverheiratete Tote?” Abbreviation: AMMitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung 111 (1996): 149–90; Sabetai, “Marker Vase or Burnt Offering? The Clay Loutrophoros in Context,” in Shapes and Uses of Greek Vases (7th–4th Centuries B.C.), eds. A. Tsingarida and L. Bavay (Brussels, 2009), 291–306.

The iconography of loutrophoroi in the Classical period is dominated by domestic and nuptial imagery as well as funerary scenes, with the find context, when known, often coinciding with the imagery. Thus, funerary iconography typically occurs on loutrophoroi from cemeteries, whereas the loutrophoroi from the Sanctuary of the Nymphe and caves devoted to the Nymphs are predominantly decorated with nuptial iconography. For the iconography of loutrophoroi with nuptial scenes, see R. M. Mösch, “Le mariage et la mort sur les loutrophores,”Abbreviation: AnnArchStorAntAnnali Sezione di archeologia e storia antica 10 (1988): 117–39; Sabetai, “Washing Painter,” 150–74; R. F. Sutton, “Nuptial Eros: The Visual Discourse of Marriage in Classical Athens,” Abbreviation: JWaltThe Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 55–56 (1997–98): 27–48; J. H. Oakley and R. H. Sinos, The Wedding in Ancient Athens (Madison, WI, 2002), 43–51; Sabetai, “Aspects of Nuptial and Genre Imagery in Fifth-Century Athens: Issues of Interpretation and Methodology,” in Abbreviation: Athenian Potters and PaintersAthenian Potters and Painters: The Conference Proceedings. 3 vols. Vol. 1, edited by J. H. Oakley, W. D. E. Coulson, and O. Palagia. Oxbow Monograph 67. Vol. 2, edited by J. H. Oakley and O. Palagia. Vol. 3, edited by J. H. Oakley. Oxford, 1997 (vol. 1), 2009 (vol. 2), 2014 (vol. 3), 319–35. Scenes on the neck of loutrophoroi with nuptial iconography often display multiple women, either individual women divided by strap handles between obverse and reverse on the amphora type or women standing next to each other on the hydria type. It is unclear which scheme Princeton’s fragment followed. Battle scenes are also quite common on loutrophoroi, perhaps to be associated with the death of unmarried soldiers: see J. D. Beazley, “Battle-Loutrophoros,” Museum Journal: University of Pennsylvania 23 (1932–33): 4–22; P. Hannah, “The Warrior Loutrophoroi of Fifth-Century Athens,” in War, Democracy and Culture in Classical Athens (Cambridge, UK, 2010), ed. D. M. Pritchard, 266–303; A. Schwarzmeier, “Grabmonument und Ritualgefäß: Zur Kriegerlutrophore Schliemann in Berlin und Athen,” in Keraunia: Beiträge zu Mythos, Kult und Heiligtum in der Antike, ed. O. Pilz and M. Vonderstein (Berlin, 2011), 115-30.