Provenance

Before 1986, Zürich market; 1986, sale, Atlantis Antiquities, Ltd. (New York, NY) to Princeton University.

Shape and Ornament

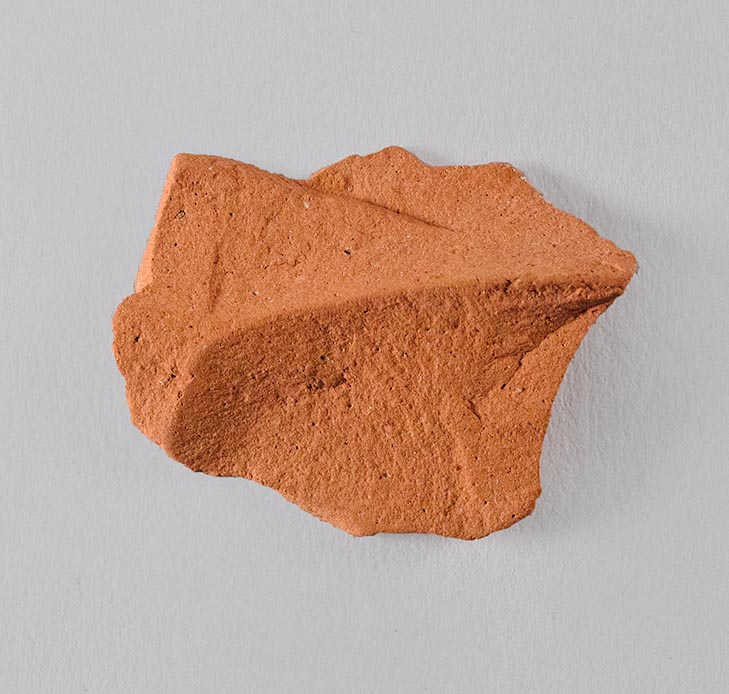

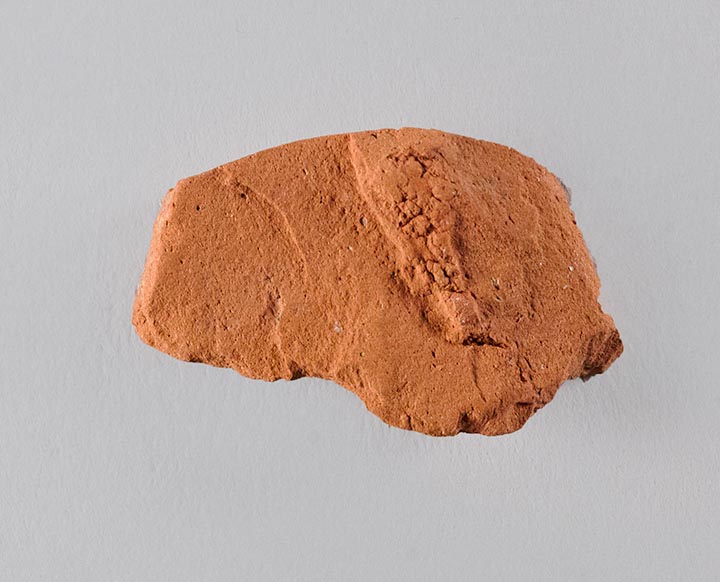

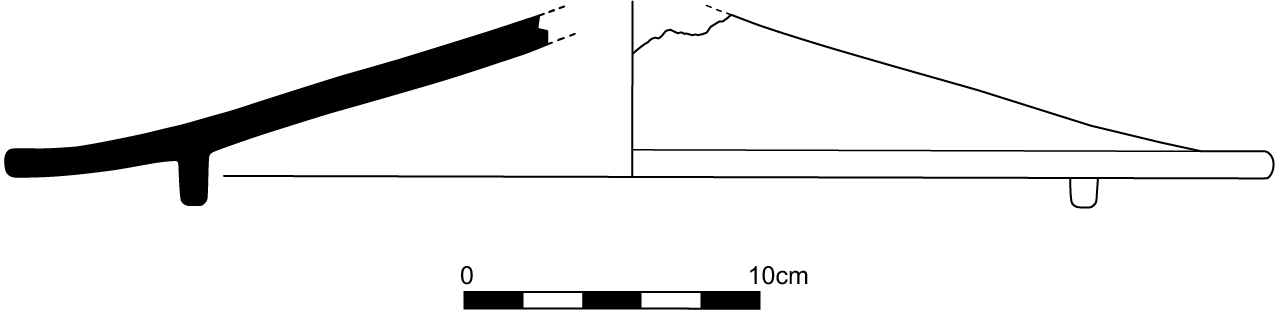

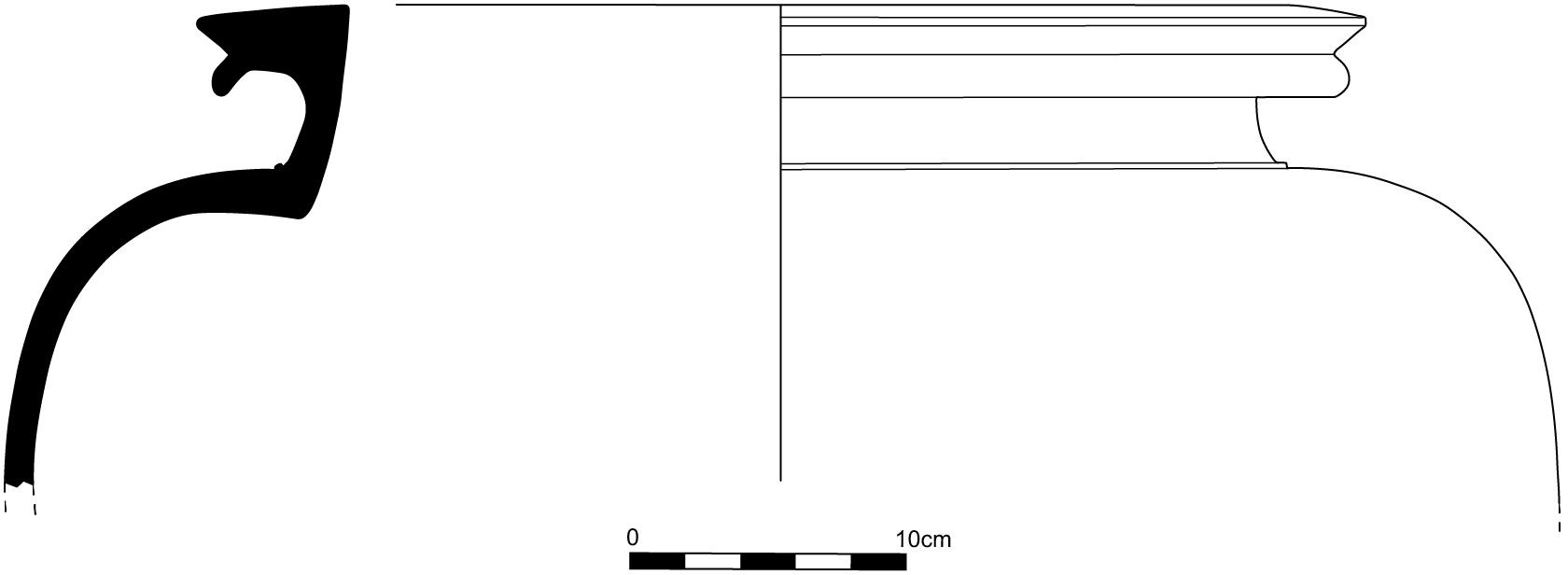

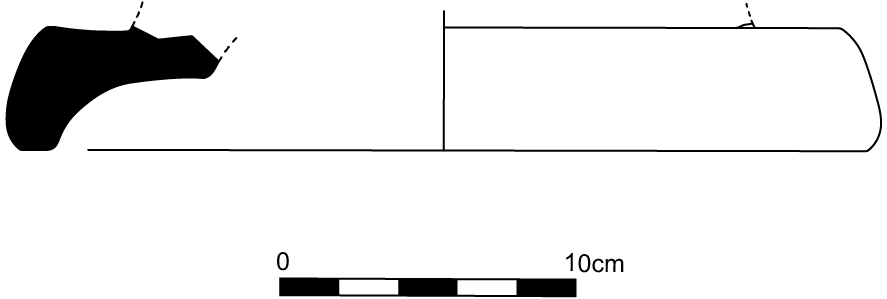

Body (Fragment b; pl. 12.1–3). Wide, overhanging rim, molded in two degrees: sharply angular black lip above a painted ovolo molding. On the upper surface, red-figure palmettes enclosed in tendrils alternate on either side of a common stem. Underside of overhang black. Neck black on the exterior and streaky black inside. Fillet separating neck from shoulder. Shoulder quickly curves down to the widest diameter of the vessel; interior of body streaky black. Around the shoulder, beneath a narrower band of egg pattern, is a band of red-figure palmettes (alternately up and down), linked by enclosing tendrils with addorsed lotus blossoms. Hollow disk foot (Fragment f; pl. 14.1–2), with slightly concave upper surface; all black except for reserved resting surface.

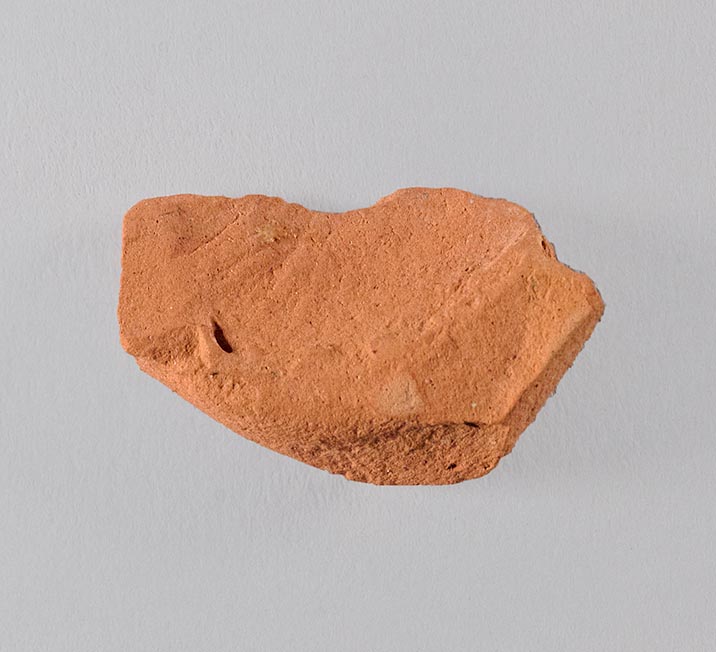

Lid (Fragment a; pl. 13.1–3). Slightly conical, and once topped with a central knob, now lost; the central circle black where preserved. Ring of right-facing black palmettes circling the center, enclosed and connected by thin tendrils, with small circles in the interstices. Figural frieze framed above and below by reserved stripes. Straight rim, painted with egg pattern, flattening to a horizontal profile; outer edge black. On the reserved underside, a prominent flange fits neatly within the mouth of the dinos, showing clearly that the lid belongs, and yielding an approximate diameter for the interior of the mouth of 31.5 cm.

Subject

Lid (Fragment a; pl. 13.1–3). Centauromachy, with death of Kaineus. Six figures are preserved, four completely and two partially. At the far left stands a partially preserved Lapith warrior, facing left and wearing a cuirass over a chitoniskos, a crested helmet, and greaves. His left leg bends beneath him, suggesting that he is falling backward. A spear extends behind him, disappearing behind his thigh; judging from its position, the warrior has just dropped it. Behind him, a balding centaur with a black beard moves to the right, his torso partially twisted back and shown in three-quarter view, as is his face, the snub nose rendered as a circle. He grasps a tree with both hands, held across his body. The forelegs of his equine lower half stretch out diagonally in front of him. Before him another centaur moves to the right, his head in profile; he has a full head of hair, a black beard, and a snub nose. He twists back, his torso frontal, to hurl a large boulder with both hands. A second boulder lies between his legs. His left foreleg is raised and overlaps slightly with Kaineus’s upper thigh. The latter, already driven halfway into the ground, turns his head to the left, with his body frontal. He raises a sword over his head in his right hand and carries a foreshortened shield on his left arm, its interior and part of the porpax (strap for the arm) visible. He wears a crested Attic helmet with raised cheek flaps and a cuirass over a chitoniskos. The shoulder flaps of the cuirass are decorated with simple rosettes. Attacking him from the right is a third centaur, balding and with a brown beard. He assaults Kaineus with a tree, which he grasps with both hands as he twists his body back. His right foreleg is raised, as if to strike Kaineus. At the far right, a partially preserved Lapith warrior charges to the right. He is nude except for a cloak over his right shoulder, a crested helmet, and greaves. In his lowered right hand he holds a sword across his upper thigh.

Body (Fragment b; pl. 12.1–3). Reclamation of Helen. Portions of five figures are preserved, with most of their lower bodies lost. At the far left stands a woman looking left but perhaps moving right, to judge from her slightly leaning posture. She wears a chiton and a himation with a brown hem, and with her left hand (drawn as right), she plucks a sakkos or veil from her head. Short curls fall over her forehead. She extends her right arm toward a fluted Ionic column surmounted by a stepped molding with a black mutule. To her right, a second female, probably Aphrodite, stands with a frontal body and head in profile to the right. She has long hair, with several individual tresses bound by a long, reserved hair band tied at the back. Beneath an open himation, draped over both shoulders, she wears a long dotted peplos with bands of s’s at the neck and waist. She raises her right arm in response to the gestures of Helen, who runs toward her from the right. Aphrodite’s left arm is bent at the waist, the hand again drawn as right. Helen turns her head to the right but moves to the left, reaching with both hands for the goddess. She wears a sakkos, earrings, a short shoulder mantle, a himation, and a chiton. Short curls fall over her forehead. Her bearded husband, Menelaos, rushes to the left, his head in profile and the back of his cuirass turned toward the viewer. The large shield covering his left arm and shoulder is foreshortened in three-quarter view, preserving a shield device of the hindquarters and tail of a lion in silhouette. He wears an Attic helmet, the crest of which largely disappears beneath the ornamental border above. The raised cheek flaps reveal stringy sideburns, and his long hair flows over and behind his right shoulder. His cuirass is decorated with a band of s’s. Although only partially preserved, the scabbard on his left side is clearly empty, suggesting that Menelaos is either carrying his sword or has just dropped it, as he is wont to do in this circumstance. Part of a second warrior stands behind Menelaos, facing right. He grips a spear in his raised right hand and wears a crested helmet.

Attribution and Date

Body. Copenhagen Painter (Syriskos) [J. R. Guy]. Lid. Syriskos Painter [J. R. Guy]. Circa 470–460 BCE.

Dimensions and Condition

Fragment a (lid; pl. 13.1–3): h. 6.5 cm; est. diam. 42.0–43.0 cm; thickness 0.95–1.23 cm.

Fragment b (body rim, shoulder, and upper body; pl. 12.1–3): h. 18.3 cm; est. diam. 42.5 cm.

Fragment c (body rim and shoulder; pl. 13.4): h. 8.0 cm.

Fragment d (body rim and neck; pl. 13.5): h. 7.6 cm.

Fragment e (shoulder; pl. 14.3–4): 17.5 × 4.9 cm; thickness 1.2–1.8 cm.

Fragment f (foot; pl. 14.1–2): h. 4.3 cm; diam. 29.7 cm.

Fragment g (neck; pl. 14.5–6): 6.5 × 8.2 cm.

Fragment h (neck; pl. 14.5–6): 3.9 × 3.7 cm.

Fragment i (body rim; pl. 14.7): 3.0 × 11.0 cm.

Fragment j (body rim, ovolo molding; pl. 14.7): 1.9 × 6.6 cm; thickness 1.0 cm.

Fragment k (body rim, ovolo molding; pl. 14.7): 1.9 × 3.8 cm; thickness 0.6 cm.

Fragment l (body rim; pl. 14.10–11): 2.3 × 2.2 cm; thickness 0.6 cm.

Fragment m (body; pl. 14.12–13): 1.8 × 1.1 cm; thickness 0.4 cm.

Fragment n (body; pl. 14.14–15): 3.0 × 2.1 cm; thickness 0.6 cm.

Fragment o (body; pl. 14.16–17): 1.8 × 1.6 cm; thickness 0.4 cm.

Fragment p (body; pl. 14.18–19): 1.7 × 1.0 cm; thickness 0.4 cm.

Fragment q (lid rim; pl. 14.8–9): 9.2 × 4.3 cm; thickness 0.8 cm.

Many joining fragments form the two principal fragments, Fragment a (lid) and Fragment b (part of the body rim, shoulder, and upper body). Approximately half of the lid is extant; large gaps are restored in plaster and painted black. Missing pieces of the body, primarily the neck, are restored in plaster and painted red. Small losses along many of the joins, and some minor chipping and flaking of the black gloss, which in places is misfired streaky, mottled red: e.g., between Helen’s arms, and much of the foot. Nearly the entire circumference of the foot (Fragment f) is preserved, mended from several fragments; losses are mostly confined to the areas along the joins. Nonjoining fragments (Fragments c–e and g–q) come from the rim, neck, and shoulder of the dinos. Fragment m preserves a small section of drapery, the only fragment aside from Fragment a and Fragment b with figural decoration. Legs of all the surviving figures are lost.

Technical Features

Preliminary sketch, including a sketch of an upward-facing palmette underneath several of the right-facing black palmettes on the lid. Relief contours throughout, including the ornament. Accessory color. Red: garland in the hair of the centaur to the left of Kaineus; leaves of the trees; inscriptions. Dilute gloss: thinning hair of the centaur at far left; beard and hair of the centaur to the right of Kaineus; musculature of the equine bodies; abdominal muscles of the nude Lapith at the right; fold lines of Aphrodite’s peplos; tresses of the three women.

Inscriptions

MO to the right of the column. HE[Λ]ENE to the left of Helen’s head; retrograde. MENEΛEOS to the left of Menelaos, curving along the contour of the shield; retrograde.

Bibliography

Abbreviation: Princeton RecordRecord of the Princeton University Art Museum. (1942– ). 46 (1987): 45–46 [illus.]; L. B. Gahli-Kahil, in Abbreviation: LIMCLexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae. 1981–2009 4 (1988), 544, pl. 342, no. 278, s.v. “Hélène”; Abbreviation: Mangold, Kassandra in AthenM. Mangold. Kassandra in Athen: Die Eroberung Trojas auf attischen Vasenbildern. Berlin, 2000, 195, no. IV 38; J. M. Padgett, “Red-Figure Dinos Fragments with the Reclamation of Helen and the Death of Kaineus,” in Abbreviation: Padgett, Centaur’s SmileJ. M. Padgett, with contributions by W. A. P. Childs et al. The Centaur’s Smile: The Human Animal in Early Greek Art. Princeton, 2003, 170–73, no. 28; S. D. Pevnick, “Foreign Creations of the Athenian Kerameikos: Images and Identities in the Work of Pistoxenos-Syriskos” (PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles, 2011), 277, no. 074; J. R. Guy, “A Matter of Style/Why Style Matters: A Birth of Athena Revisited,” in Approaching the Ancient Artifact: Representation, Narrative, and Function; A Festschrift in Honor of H. Alan Shapiro, ed. A. Avramidou and D. Dimitriou (Berlin, 2014), 346, fig. 4; Pevnick, “Le style est l’homme même? On Syriskan Attributions, Vase Shapes, and Scale of Decoration,” in Töpfer Maler Werkstatt: Zuschreibungen in der griechischen Vasenmalerei und die Organisation antiker Keramikproduktion, ed. N. Eschbach and S. Schmidt (Munich, 2016), 43, fig. 8; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 41052.

Comparanda

For the Syriskos Group, see Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 256–60, 1640–41; Abbreviation: ParalipomenaJ. D. Beazley. Paralipomena: Additions to Attic Black-Figure Vase-Painters and to Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. Oxford, 1971 351–53; Abbreviation: BAdd2Carpenter, T. H., ed. 1989. Beazley Addenda: Additional References to ABV, ARV2, and Paralipomena. 2nd ed. Oxford: Published for the British Academy by Oxford University Press. 204–5; Abbreviation: Beazley, Vases in American MuseumsJ. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figured Vases in American Museums. Cambridge, Mass., 1918, 63–65 [63, n. 1 for the Copenhagen Painter]; C. Isler-Kerényi, Lieblinge der Meermädchen: Achilleus und Theseus auf einer Spitzamphora aus der Zeit der Perserkriege (Zürich, 1977); C. Weiss, “Spitzamphora des Syriskos,” in Mythen und Menschen: Griechische Vasenkunst aus einer deutschen Privatsammlung, ed. G. Günter (Mainz am Rhein, 1997), 104–11; S. M. Lubsen Admiraal, “The Getty Krater by Syriskos,” in Proceedings of the XVth International Congress of Classical Archaeology, Amsterdam, July 12–17, 1998, eds. R. F. Docter and E. M. Moormann (Amsterdam, 1999), 239–41; Pevnick, “ΣϒPIΣKOΣ EΓPΦΣEN: Loaded Names, Artistic Identity, and Reading an Athenian Vase,” Abbreviation: ClAntClassical Antiquity 29 (2010): 222–53; id. “Foreign Creations”; P. Persano, “Syriskos a Chiusi: un ‘nuovo’ stamnos del Pittore di Copenhagen fra Atene e l’Etruria,” Abbreviation: BABeschBulletin antieke beschaving. Annual Papers on Classical Archaeology 90 (2015): 43–61; Pevnick, “Le style est l’homme même?” 36–46; H. A. Shapiro, “Syriskos and the Athenian Black- and Red-Figure Pointed Amphora,” in Ὁ παῖς καλός: Scritti di archeologia offerti a Mario Iozzo per il suo sessantacinquesimo compleanno, eds. B. Arbeid, E. Ghisellini, and M. R. Luberto (Rome, 2022), 353–66.

Although the Syriskos Painter remains anonymous, Guy, in an unpublished lecture delivered in Copenhagen in 1987, attributed to the Copenhagen Painter a calyx-krater that was signed as painter by Syriskos, a name previously associated only with potter signatures: formerly Malibu 92.AE.6 (Lubsen Admiraal, “The Getty Krater”; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 28083). With this attribution, it is now generally agreed that Syriskos was the actual name of the Copenhagen Painter. To avoid confusion, this entry will maintain the name Copenhagen Painter.

For Beazley (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 256), the Syriskos Group “consists of two artists, ‘brothers,’ the Copenhagen Painter and the Syriskos Painter, who are sometimes hard to tell apart.” Beazley’s own hesitation in distinguishing between the two painters is made clear by the differences in attributions between his initial lists published in Abbreviation: Beazley, Vases in American MuseumsJ. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figured Vases in American Museums. Cambridge, Mass., 1918 and his later lists in Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963. The Aegisthus Painter, whose style, Beazley writes (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 504), “seems derived from the later style of the Copenhagen Painter,” likely forms a third major painter in the same group. For the conflation of the Syriskos and Copenhagen Painters as a single artist, see J. Boardman, Athenian Red-Figure Vases: The Archaic Period (Oxford, 1975), 113–14; Pevnick, “Foreign Creations,” esp. 103–25; id., “Le style est l’homme même,” 36–46; P. Sapirstein, “Painters, Potters, and the Scale of the Attic Vase-Painting Industry,” Abbreviation: AJAAmerican Journal of Archaeology 117 (2013): 503. For the conflation of all three artists from the group, the Syriskos, Copenhagen, and Aegisthus Painters, see S. B. Matheson, “A Red-Figure Krater by the Aegisthus Painter,” Abbreviation: YaleBullYale University Art Gallery Bulletin 40 (1987): 6–7. Simon combines the Aegisthus and Copenhagen Painters, while keeping the Syriskos Painter separate: E. Simon, “Early Classical Vase-Painting,” in Greek Art: Archaic into Classical. A Symposium Held at the University of Cincinnati, April 2–3, 1982, ed. C. Boulter (Leiden, 1982), 73–74. For the separation of the Syriskos and Copenhagen Painters, following Beazley (and here maintained), see Abbreviation: Robertson, Art of Vase-PaintingM. Robertson, The Art of Vase-Painting in Classical Athens. Cambridge, 1992, 140; Guy, “Matter of Style,” 346; Abbreviation: Williams, “Workshop View”Williams, D. 2017. “Beyond the Berlin Painter: Toward a Workshop View.” In Padgett, Berlin Painter, 144–88. 162.

Guy, in his 1987 unpublished lecture in Copenhagen, attributed the lid (Fragment a) of Princeton’s dinos to the Syriskos Painter and the body to the Copenhagen Painter, a separation endorsed by Padgett (“Red-Figure Dinos Fragments,” 172). Guy (“Matter of Style,” 346–47) also has attributed a volute-krater on loan from the Fondation Morat to the Archaeological Collection of the University of Freiburg (J. Neils, The Youthful Deeds of Theseus [Rome, 1987], 156, no. 26; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 44988) to both the Copenhagen and Syriskos Painters, with the Syriskos Painter responsible for the smaller figures on the neck and the Copenhagen Painter for the large figures on the body. Three pointed amphorae attributed to the Copenhagen Painter, all showing centauromachies in small scale on the shoulder, bolster Beazley’s separation of the two artists: one in Switzerland, Zürich L5 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1656.2 bis [as the Oreithyia Painter]; Isler-Kerényi, Lieblinge; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 275252); another in the White-Levy Collection in New York, once on loan to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, L.1999.10.15 (D. von Bothmer, Glories of the Past: Ancient Art from the Shelby White and Leon Levy Collection, exh. cat., Metropolitan Museum of Art [New York, NY, 1990], 168–70, no. 121; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 43937); and a third now in an American private collection (Christie’s, Antiquities, auc. cat., October 6, 2011, London, lot 85; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 30676). The iconography is quite close, in particular, the poses of the figures in the four centauromachies: cf., for instance, on all four vases, the centaur with one forefoot raised, gripping a tree in both hands while twisting its body back. Cf. also the depiction of Kaineus on Princeton’s lid with the New York amphora (supra). The four centauromachies also share an interest in daring poses, such as the three-quarter face of the centaur in Princeton, and the frontal Kaineus and fallen centaur on the amphora in Germany. However, the care with which the centaurs on Princeton’s lid are differentiated from one another in hairstyles and facial features is far more detailed than on the other three centauromachies: e.g., the rendering of the centaurs’ noses. Aside from their balding heads, the centaurs on the three amphorae attributed to the Copenhagen Painter essentially resemble their human counterparts, in contrast to their more brutish portrayal on Princeton’s lid, where they also lack the detailed abdominal musculature of the centaurs by the Copenhagen Painter. Compositionally, Princeton’s lid appears more static, a feature due in large part to the avoidance of overlapping elements: cf. in particular the intensity of the scene in Zürich, with several overlapping figures, a phenomenon also found, to a lesser degree, on the amphora in a German private collection. The strong similarities among the four centauromachies, in addition to the several distinct features of Princeton’s lid, suggest two separate but closely related personalities, or stylistic “brothers.”

The drawing on the body of the dinos supports this claim. Only one other Reclamation of Helen survives from either the Syriskos or Copenhagen Painter, a hydria in London attributed by Beazley to the Syriskos Painter: London E 161 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 262.41; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 202723). Details in the draftsmanship of the London hydria and Princeton’s dinos separate the two hands. The Menelaos in London more closely resembles Kaineus on Princeton’s lid than Menelaos on the dinos, whose long tresses and luxuriant sideburns are completely absent on both the London hydria and the lid of the Princeton dinos. The slightly open mouth of Princeton’s Menelaos is paralleled by the dying Kaineus on the amphora in Zürich (supra), while the Princeton Aphrodite may be compared with one of the Nereids on the amphora in Zürich. Perhaps the closest parallel for the Menelaos in Princeton is Perithous on the pointed amphora by the Copenhagen Painter in an American private collection (supra), with his black helmet, cuirass with a band of s’s, and shield with a nearly identical lion device. As noted by Pevnick (“Foreign Creations,” 123–24), Menelaos’s helmet on both the Princeton dinos and the London hydria are overlapped by the upper border, a rather unusual detail, as helmets more often burst through such ornamental bands. However, such overlapped helmets also occur on the pointed amphora in Germany, attributed to the Copenhagen Painter. Pevnick (ibid., 123–24) also discusses similarities between the figure of Helen on Princeton’s dinos and that of the woman rushing to Helen’s aid on the hydria in London, though the latter has longer features and a more pointed chin. Closer to the softer features of the women in Princeton are the daughters of Pelias on a stamnos attributed to the Copenhagen Painter: Munich SH 2408 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 257.8, 258, 1640; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 202926).

Attic dinoi were relatively popular in early black-figure workshops, their rounded bodies set upon separately made stands: see D. von Bothmer, “An Attic Black-Figured Dinos,” Abbreviation: BMFABulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 46 (1948): 42–48; D. Williams, “Sophilos in the British Museum,” in Abbreviation: GkVasesGetty 1Frel, J., and S. K. Morgan, eds. 1983. Greek Vases in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Occasional Papers on Antiquities 1. Malibu: J. Paul Getty Museum., 9–34; A. B. Brownlee, “Sophilos and Early Black-Figured Dinoi,” in Proceedings of the 3rd Symposium on Ancient Greek and Related Pottery, Copenhagen, August 31–September 4, 1987, eds. J. Christiansen and T. Melander (Copenhagen, 1988), 80–87; M. Iozzo, “Un nuovo dinos da Chiusi con le nozze di Peleus e Thetis,” in Shapes and Images: Studies on Attic Black-figure and Related Topics in Honour of Herman A. G. Brijder, eds. E. Moormann and V. V. Stissi (Leuven, 2009), 63–85; A. Brownlee, “Antimenean Dinoi,” in Abbreviation: Athenian Potters and PaintersAthenian Potters and Painters: The Conference Proceedings. 3 vols. Vol. 1, edited by J. H. Oakley, W. D. E. Coulson, and O. Palagia. Oxbow Monograph 67. Vol. 2, edited by J. H. Oakley and O. Palagia. Vol. 3, edited by J. H. Oakley. Oxford, 1997 (vol. 1), 2009 (vol. 2), 2014 (vol. 3), 509–22. Red-figure dinoi, however, are very rare, with no examples from the Pioneer Workshop. The earliest known, from the 490s, is a rim fragment by the Kleophrades Painter: Malibu 76.AE.132.1B and 82.AE.50 (M. Robertson, “Fragments of a Dinos and a Cup Fragment by the Kleophrades Painter,” in Abbreviation: GkVasesGetty 1Frel, J., and S. K. Morgan, eds. 1983. Greek Vases in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Occasional Papers on Antiquities 1. Malibu: J. Paul Getty Museum., 51–54; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 28779). Closer to Princeton’s dinos in the scheme of decoration is a dinos by the Berlin Painter: Basel Lu 39 (L. Lullies, “Der Dinos des Berliner Malers,” Abbreviation: AntKAntike Kunst 14 [1971]: 44–55, pl. 17–20.1; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 308). On both, figural decoration is confined to a monumental scene on the body of the dinos, with subsidiary ornament relegated to the shoulder and the overhang and top of the rim. Gaunt, based on the similar decorative schemes, suggests that the Berlin Painter’s dinos “paved the way” for the Copenhagen Painter’s dinos, among others: J. Gaunt, “The Berlin Painter and His Potters,” in Abbreviation: Padgett, Berlin PainterJ. M. Padgett, with contributions by N. T. Arrington et al. The Berlin Painter and His World: Athenian Vase-Painting in the Early Fifth Century B.C. Princeton, 2017, 97–98. Although Gaunt shows that the Copenhagen and Berlin Painters collaborated with the same potters, the potting of the Berlin Painter’s dinos, with its footless body and double beveled rim, is in the tradition of black-figure dinoi by the Antimenes Painter and others, and differs significantly from the vessel in Princeton. Much closer, albeit significantly smaller, is a footed dinos by the Syleus Painter: Malibu 89.AE.73 (K. Clinton, Myth and Cult: The Iconography of the Eleusinian Mysteries [Stockholm, 1992], 188–90, figs. 43–47; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 43376), cf. the overall decorative scheme, the molded rim, and the profile of the body. Only one other dinos has been connected with the Syriskos Group, a small and poorly preserved body fragment that shows Herakles’s fight against the Nemean lion: Athens, Kerameikos 8716/8785, associated by Knigge with the Syriskos Painter (U. Knigge, “Kerameikos,” Abbreviation: AAArchäologischer Anzeiger [1995]: 633, fig. 11; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 28583).

Although the painters of the Syriskos Group often decorated large pots with striking floral designs, those on the dinos are not exactly paralleled elsewhere in the group. Two pointed amphorae by the Copenhagen Painter bear similar but distinctive palmette-and-lotus chains: American private collection (supra), which bears a double palmette-and-lotus chain; and London E 350 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 256.2, 1589; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 202921), on which only single lotuses alternate with palmettes. The double palmette-and-lotus chain is not uncommon and occurs in the workshops of other painters, such as the Syleus Painter, whose pointed amphora and dinoi, as mentioned above, resemble those by the Copenhagen and Syriskos Painters: cf., by the Syleus Painter, Brussels R 303 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 249.6, 1639; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 202485). The remarkable palmettes on top of the Princeton rim, which are linked to a central “vine,” are so far unparalleled. The black palmettes on the lid are also unprecedented within the oeuvre of the Syriskos Painter, but he did place a black lotus-and-palmette chain on the neck of the fragmentary neck-amphora Florence 7 B42 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 261.28; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 202982). The sketch line for a palmette beneath the black palmettes suggests that the artist originally intended to execute a band of red-figure florals.

For the iconography of Kaineus, see B. Cohen, “Paragone: Sculpture versus Painting; Kaineus and the Kleophrades Painter,” in Ancient Greek Art and Iconography, ed. W. Moon (Madison, WI, 1983), 171–92; E. Laufer, Kaineus: Studien zur Ikonographie. Abbreviation: RdARivista di archeologia Suppl. 1 (Rome, 1985); E. Laufer, in Abbreviation: LIMCLexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae. 1981–2009 5 (1990), 884–91, pls. 563–76, nos. 1–83; s.v. “Kaineus”; M. Leventopoulou et al., in Abbreviation: LIMCLexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae. 1981–2009 8 (1997), 688–91, pls. 430–40, nos. 200–219, s.v. “Kentauroi et Kentaurides.” Although none of the figures on the lid are labeled, the central warrior must surely be Kaineus, the Lapith hero endowed with impenetrable skin, whom the centaurs could defeat only by beating him into the ground with tree trunks and stones. Because more than half of the lid is missing, it is not clear whether Theseus and Perithous were depicted. Pevnick (“Foreign Creations,” 120) cautiously suggests that the partially preserved figure at the right, the only figure depicted with a bare chest and thus perhaps designated as heroic, might be Theseus. Although such a partially nude figure does not occur in the three related Syriskan centauromachies, in other depictions of the death of Kaineus, fully nude or partially nude figures often fight the centaurs: e.g., by the Niobid Painter, Bologna 268 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 598.1; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 206929); by Myson, Naples 81399 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 239.18; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 202367). On the Copenhagen Painter’s pointed amphora in an American private collection (supra), Theseus—identified by inscription—is fully armed.

For the Reclamation of Helen, see L. B. Ghali-Kahil, Les enlèvements et le retour d’Hélène dans les textes et les documents figurés (Paris, 1955); P. A. Clement, “The Recovery of Helen,” Abbreviation: HesperiaHesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens 27 (1958): 47–73; Ghali-Kahil in Abbreviation: LIMCLexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae. 1981–2009 4 (1988), 537–52, pls. 329–57, nos. 210–372, s.v. “Hélène”; G. Hedreen, “Image, Text and Story in the Recovery of Helen,” Abbreviation: ClAntClassical Antiquity 15 (1996): 152–84; A. Dipla, “Helen, the Seductress?” in Greek Offerings: Essays on Greek Art in Honour of John Boardman, ed. O. Palagia (Exeter, 1997), 119–30; Gahli-Kahil in Abbreviation: LIMCLexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae. 1981–2009 8 (1997), 839–41, pls. 564–66, nos. 44–68, s.v. “Menelaos”; Abbreviation: Mangold, Kassandra in AthenM. Mangold. Kassandra in Athen: Die Eroberung Trojas auf attischen Vasenbildern. Berlin, 2000, 80–102; G. Hedreen, Capturing Troy: The Narrative Functions of Landscape in Archaic and Early Classical Greek Art (Ann Arbor, MI, 2001), 22–63; M. Recke, Gewalt und Leid: Das Bild des Krieges bei den Athenern im 6. und 5. Jh. v. Chr. (Istanbul, 2002), 20–52; S. Masters, “The Abduction and Recovery of Helen: Iconography and Emotional Vocabulary in Attic Vase-Painting, c. 550–350 BCE” (PhD diss., University of Exeter, 2012); M. Stansbury-O’Donnell, “Menelaos and Helen in Attic Vase-Painting,” in Abbreviation: Athenian Potters and Painters 3Oakley, J. H., ed. 2014. Athenian Potters and Painters. Vol. 3. Oxford: Oxbow Books., 255–65; A. R. Stelow, Menelaus in the Archaic Period: Not Quite the Best of the Achaeans (Oxford, 2020), 207–27. As opposed to the black-figure scenes of the Reclamation, which portrayed Menelaos leading Helen away, scenes of pursuit dominate the red-figure repertoire. Already in the sixth century, Oltos seems to have produced the first example: Paris, Louvre G 3 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 53.1; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 200435). For the suggestion that the iconography of pursuit in the Reclamation of Helen was influenced by the popularity of scenes showing the rape of Kassandra, see Recke, Gewalt und Leid, 41. For the suggestion that the pursuit motif was influenced by generic ephebic or divine pursuits, see Stansbury-O’Donnell, “Menelaos and Helen,” 248.

As discussed by Dipla (“Helen, the Seductress,” 121–23), Menelaos’s sword becomes an important iconographic element in scenes of pursuit, characterizing his action as menacing and threatening if he brandishes the sword, or as lustful if he has already dropped his sword or keeps it in its sheath. Although Menelaos’s sheath is empty on Princeton’s dinos, it is unclear whether he holds the sword in his right hand or has already dropped it upon seeing Helen. The other Syriskan Reclamation scene on London E 161 (supra) depicts Menelaos with sword still in hand, and although there are examples of the dropped sword motif early in the fifth century, primarily associated with the workshop of the Berlin Painter (cf. Vienna 741: Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 203.101; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 201909), the motif becomes popular only in the mid- to late fifth century: see Stansbury-O’Donnell, “Menelaos and Helen,” 259–60.

Padgett (“Red-Figure Dinos Fragments,” 170) identified the central woman wearing the ornate, spotted peplos as Aphrodite, playing the part of Helen’s protector, “standing unmoving and serene,” unlike the panicked woman at the far left. Aphrodite frequently appears in depictions of the Reclamation of Helen: see A. Delivorrias, in Abbreviation: LIMCLexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae. 1981–2009 2 (1984), 140–41, pls. 143–45, nos. 1470–83, s.v. “Aphrodite.” In such instances, she is often identified by a scepter, crown, or by the presence of Eros, all of which are absent on Princeton’s dinos. The woman at the far left remains unidentified, and the MO inscription by her head does not clarify the matter. Unnamed women are common in depictions of the Reclamation; sometimes they gesture and look at Helen and Menelaos, unlike the woman on Princeton’s dinos, who turns her back to them: cf. the hydria in London by the Syriskos Painter (supra). As it is likely that this scene is but one of a series that continued around the entire vessel, forming part of an expansive depiction of the sack of Troy, the unidentified Trojan woman was perhaps fleeing from another Greek warrior. For the Reclamation of Helen as part of a larger Iliupersis scene, cf. a cup by Onesimos in Cerveteri, formerly Malibu 83.AE.362, 84.AE.80, and 85.AE.385 (D. Williams, “Onesimos and the Getty Iliupersis,” in Abbreviation: GkVasesGetty 5True, M., ed. 1991. Greek Vases in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Vol. 5. Occasional Papers on Antiquities 7. Malibu: J. Paul Getty Museum., 48–60, fig. 8a–n; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 13363). The woman’s agitated gesture of pulling off her sakkos is unusual in any context, and recalls the way that, on a cup fragment by Makron, Aphrodite unveils Helen to reveal her beauty to Menelaos, evoking the anakalypteria, the ritual unveiling of an Athenian bride: Princeton y1990-20 a–c (Abbreviation: Padgett, Berlin PainterJ. M. Padgett, with contributions by N. T. Arrington et al. The Berlin Painter and His World: Athenian Vase-Painting in the Early Fifth Century B.C. Princeton, 2017, 368–69, no. 83; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 22040).