Provenance

1997, gift, Emily T. Vermeule and Cornelius C. Vermeule III (Cambridge, MA) to Princeton University.

Shape and Ornament

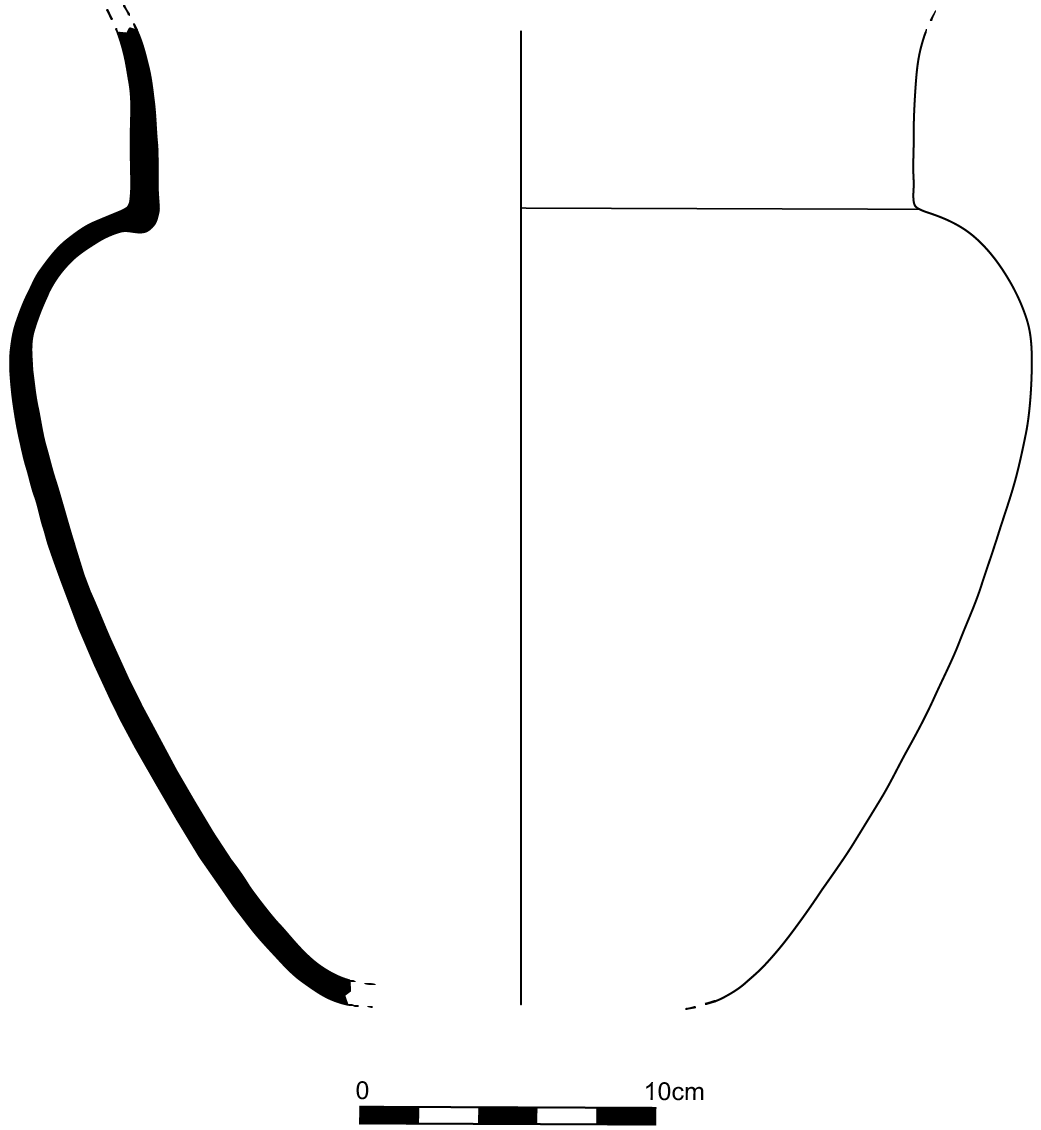

Fragments preserving most of the body and a small section of the wide, cylindrical neck. Interior of neck and body covered in streaky black gloss, except for the underside of the shoulder. Frieze of pendant lotus buds preserved in segments on neck, on sides A and B. Ovoid body broadest at the base of the handles, before narrowing quickly toward the missing foot. Swelling around the roots of handle AB. Band of tongue pattern above picture panels, which are framed laterally by ivy vines, with a reserved band below. Encircling red band below and partially overlapping reserved groundline; another encircles the top of the black rays on lower body.

Subject

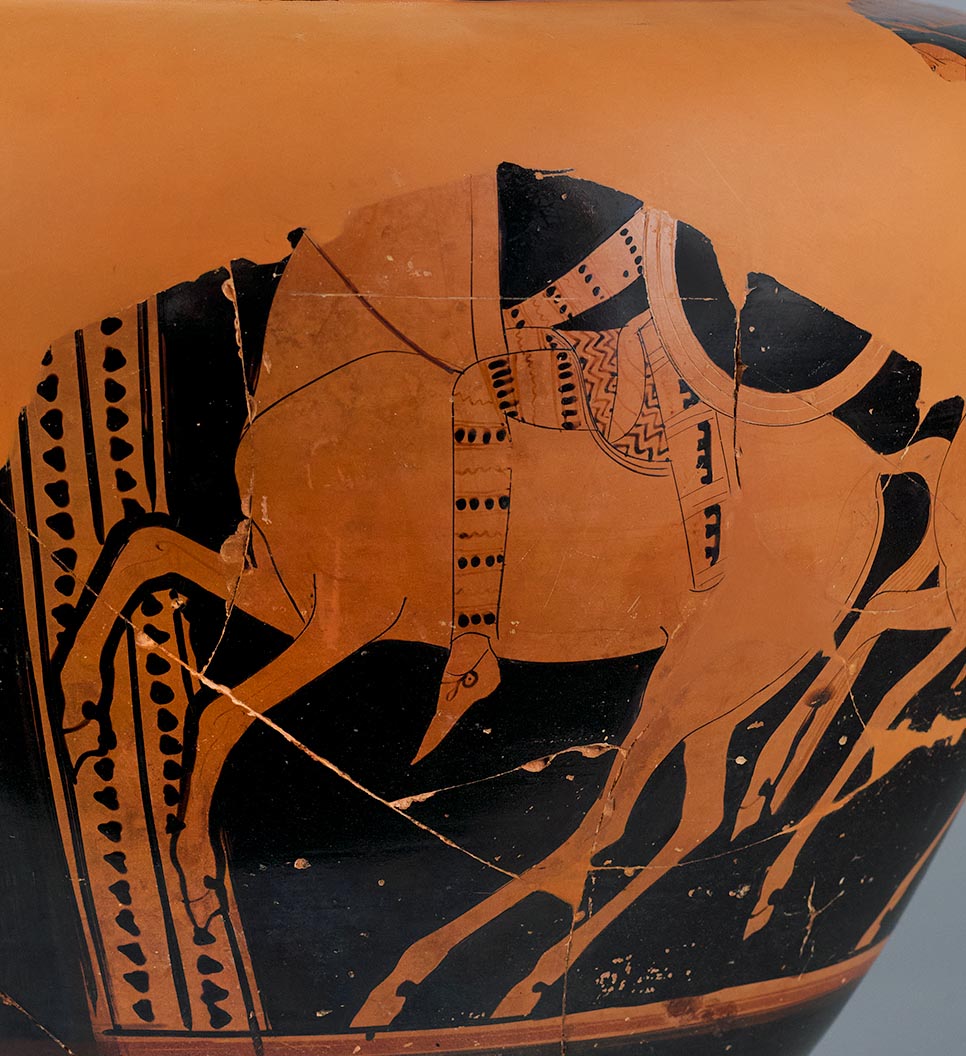

A. Two mounted Amazons, riding in profile to the left. The Amazon at left wears barbarian garb: patterned trousers and a long-sleeved tunic. The sleeves have the same design as the trousers, with alternating rows of black dots and wavy lines. The bottom of the tunic, which falls over the waist, is instead decorated with zigzag lines. The Amazon’s shoes are tied with strings. Her head and the upper half of her shield are lost, as is her horse’s head. The shield, slightly smaller than the typical Greek hoplon, is black, with a reserved rim. A large quiver or gorytos (bow case) hangs from her left hip, decorated with a battlement design. Although it does not widen at the top, the length of the object suggests that it is likely a gorytos. The galloping horse breaks through the ivy border with raised forelegs. The beardless warrior at the right wears Greek armor but is identified as an Amazon by her long black hair, individual tresses of which hang in front of her ear and over her cheeks and neck. She wears a chitoniskos underneath a cuirass with scale armor and double lappets, as well as a cloak draped over her right arm. Her Corinthian helmet is pushed back on top of her head and bursts through the tongue pattern above. A line at her ankle may indicate that she wears greaves, although there is no curve or line marking the calf. On her left arm she carries a small black shield with a reserved border, like that of the other rider, and holds a spear in her left hand. She is barefoot. Most of her horse’s head and neck, and a large portion of its body, are missing. The horse’s tail and hindquarters extend into the ivy pattern to the right of the scene, and both of its forelegs are raised off the ground.

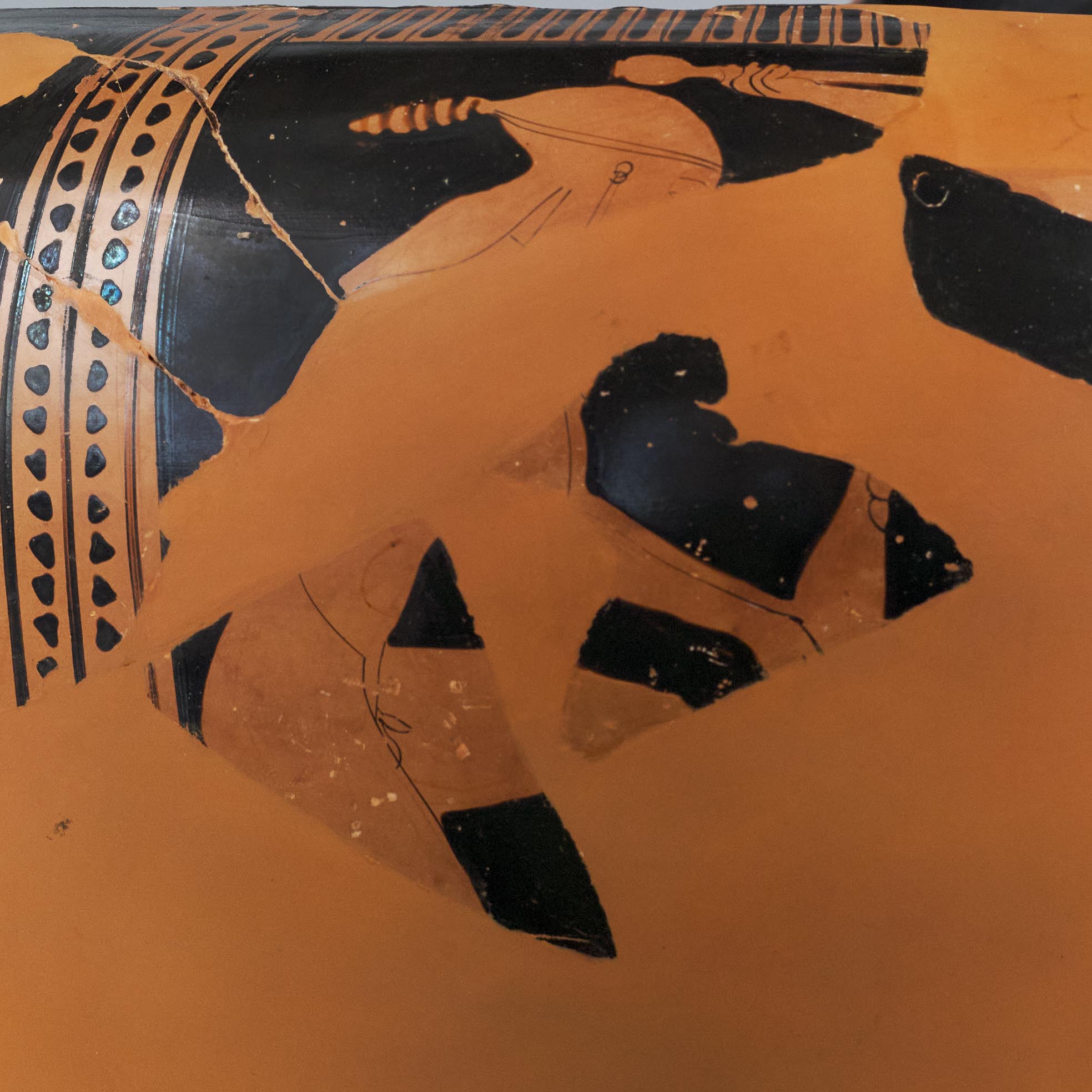

B. Arming and call to action. At the left a warrior bends over to put a greave on his raised left leg. He is nude except for an animal-skin cap of Thracian type (alopekis) with a striped tail. In the center, a second figure extends his right arm, in which he holds a trumpet (salpinx), to call the warriors to battle. Although his head is not preserved, the position of the salpinx and his backward-leaning posture suggest that he is blowing the trumpet. He, too, wears an alopekis, of which one lappet remains, and a cuirass. On his left arm he carries a reserved shield bearing a device of a flying black bird. At the right, a third warrior gestures toward the trumpeter with his raised right arm, his torso in partial three-quarter view. He is nude except for a black Chalcidian helmet that breaks through the tongue pattern above. He carries a shield decorated with a Macedonian star.

Attribution and Date

Group of Polygnotos [D. von Bothmer]. Circa 450–440 BCE.

Dimensions and Condition

h. 33.0 cm; diam. 34.6 cm. Broken and mended, with many missing pieces restored in plaster. Only two small pieces from the neck have been preserved, and the handles, rim, and foot are entirely missing. On side A, the heads of the first horseman and his steed are lost, as are parts of the body and head of the second horse, except for the very top of the head and mane. The second horseman’s upper leg is missing. The lower portion of side B, including the lower legs of all three figures, is lost. Most of the torso of the figure at the left is missing, and only portions of the extended right arm, shoulder, and shield of the middle figure remain. The upper body of the figure at the right is mostly preserved, but the upper portion of his shield is lost.

Technical Features

Preliminary sketch. Relief contours used throughout on side A, only for trumpeter’s arm and salpinx on side B. The shield rims are compass drawn. Accessory color. Dilute gloss: on side A, horses’ muscles, tails, and manes; chiton folds and flowing locks of rider at right; trousers, sleeves, quiver, and shoestrings on rider at left; on side B, muscles of the warrior donning greaves; facial features, including the lips and chin, of the helmeted warrior.

Bibliography

D. M. Buitron, Attic Vase Painting in New England Collections, exh. cat., Fogg Art Museum (Cambridge, MA, 1972), 126–27, no. 70; Abbreviation: Matheson, PolygnotosS. B. Matheson. Polygnotos and Vase Painting in Classical Athens. Madison, Wisc., 1995, 471, no. PGU 125 [not illus.]; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 4144.

Comparanda

The bibliography on the painters of the Group of Polygnotos is vast. See in particular Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1027–64, 1678–81; Abbreviation: ParalipomenaJ. D. Beazley. Paralipomena: Additions to Attic Black-Figure Vase-Painters and to Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. Oxford, 1971 442–46; Abbreviation: BAdd2Carpenter, T. H., ed. 1989. Beazley Addenda: Additional References to ABV, ARV2, and Paralipomena. 2nd ed. Oxford: Published for the British Academy by Oxford University Press. 317, 321; G. Gualandi, “Il Pittore di Kleophon,” Arte Antica e Moderna 5 (1962): 341–83; id., “Il Pittore di Kleophon rinvenute a Spina,” Arte Antica e Moderna 5 (1962): 227–60; H. Hinkel, “Der Giessener Kelchkrater” (PhD diss., Justus Liebig-Universität Giessen, 1967); E. De Miro, “Nuovi contributi sul Pittore di Kleophon,” Abbreviation: ArchCl Archeologia Classica 20 (1968): 238–48; S. Karouzou, “Stamnos de Polygnotos au Musée National d’Athènes,” Abbreviation: RARevue archéologique, n.s., 2 (1970): 229–52; K. F. Felten, Thanatos- und Kleophonmaler: Weissgrundige und rotfigurige Vasenmalerei der Parthenonzeit (Munich, 1971); C. Isler-Kerényi, “Chronologie und Synchronologie attischer Vasenmaler der Parthenonzeit,” Abbreviation: AntK-BHAntike Kunst: Beiheft 9 (1973): 23–32; E. G. Pemberton, “The Name Vase of the Peleus Painter,” Abbreviation: JWaltThe Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 36 (1977): 62–72; Y. Korshak Schwartz, “The Peleus Painter and the Art of His Time” (PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley, 1973); M. Halm-Tisserant, “Le Peintre de Curti,” Abbreviation: REARevue des études anciennes 86 (1984): 135–70; Matheson, “Polygnotos: An Iliupersis Scene at the Getty Museum,” in Abbreviation: GkVasesGetty 3Frel, J., and M. True, eds. 1986. Greek Vases in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Vol. 3. Occasional Papers on Antiquities 2. Malibu: J. Paul Getty Museum., 101–14; Abbreviation: Robertson, Art of Vase-PaintingM. Robertson, The Art of Vase-Painting in Classical Athens. Cambridge, 1992, 210–16. For the figural style of Princeton’s krater, cf. the name-vase of the Epimedes Painter, London E 450 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1043.1; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 213547); and, by the Christie Painter, London 1898,0715.1 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1048.35; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 213604). In particular, the stamnos by the Epimedes Painter relates to Princeton’s krater in the details of the clothing of the Amazon and the musculature of the horse. Most of the faces on Princeton’s krater are lost, making comparison of minor details difficult, although the head of the mounted Amazon at the right is well preserved, as is the helmeted figure on the reverse. The eyes of these two figures are drawn with two lines curving inward to form a partially open oval and a circular pupil. Such eyes are distinctive within the Group of Polygnotos, whose artists more often prefer an open triangle for the lid and a pendant pupil: cf., inter alia, by the Lykaon Painter, the eye of the seated Odysseus on Boston 34.79 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1045.2, 1679; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 213553); or, by an unnamed Polygnotan, Paris, Louvre G 414 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1051.11; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 213642). The eyes on Princeton’s krater, although strictly profile, resemble more the eyes of Elpenor on the Boston pelike (supra), who is drawn in three-quarter view. Similar execution of profile eyes occurs on the mounted Amazon on the Epimedes Painter’s name-vase in London (supra). Cf. also the eye of the satyr on side A of a stamnos by the Christie Painter: Harvard 1925.30.42 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1048.38; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 213607).

The basic decorative scheme is standard, but it is rare to find a bud frieze on both sides of the neck since it is more normally confined to the obverse: cf., by the Flying Angel Painter, Villa Giulia 985 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1642.39 ter; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 275154); by the Painter of the Louvre Centauromachy, Tarquinia RC 1960 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1088.2; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 214588); by the Eupolis Painter, South Hadley 1913.1.B.SII (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1074.1; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 214450). It should be noted that Polygnotan column-kraters are very rare, with only three other complete examples surviving: Abbreviation: Matheson, PolygnotosS. B. Matheson. Polygnotos and Vase Painting in Classical Athens. Madison, Wisc., 1995, 180, 471, nos. PGU 124, 126, 127. Only one resembles Princeton’s krater in size: Athens, Agora P 30197 (Abbreviation: Matheson, PolygnotosS. B. Matheson. Polygnotos and Vase Painting in Classical Athens. Madison, Wisc., 1995, 470, pl. 168, no. PGU 124), which also shows an Amazonomachy (the ornament and figural style, however, bear little relation). Matheson’s confinement of column-kraters to unnamed Polygnotans may provide further evidence for the suggestion that the Group of Polygnotos does not represent a single workshop but rather several workshops, including those that regularly produced column-kraters, which are related by a consistent and distinctive style. For the question of whether the Group represents a single workshop, see Abbreviation: BAdd2Carpenter, T. H., ed. 1989. Beazley Addenda: Additional References to ABV, ARV2, and Paralipomena. 2nd ed. Oxford: Published for the British Academy by Oxford University Press., xvi, s.v. “Group”; Abbreviation: Matheson, PolygnotosS. B. Matheson. Polygnotos and Vase Painting in Classical Athens. Madison, Wisc., 1995, 162–75.

Although the figures on side A bear no identifying attributes that associate them with a specific “barbarian” group—the clothing of the figure on the left, for instance, could be worn by a Scythian, Amazon, or Persian—they are most likely Amazons. Scythian archers certainly appear alongside other warriors, and individually as mounted soldiers, but rarely are they shown mounted with another mounted soldier. Much more common are Scythian archers on foot serving as squires to mounted Greek soldiers, but these largely disappear from vases after about 500 BCE. For the iconography of Scythian archers and the relationship to other warriors, see F. Lissarrague, L’autre guerrier: Archers, peltastes, cavaliers dans l’imagerie attique (Paris, 1990). For the disappearance of Scythians from Attic vase-painting in the fifth century, see R. Osborne, The Transformation of Athens: Painted Pottery and the Creation of Classical Greece (Oxford, 2018), 95–100. The long hair of the rider at the right, who wears Greek armor, ought to identify her as female, and thus an Amazon. Furthermore, although Scythians are almost always recognized by their attire, which precludes the identification of the mounted warrior at the right as a Scythian, Amazons are often depicted in typical Greek armor. Mounted Amazons abound in the large workshop of the Group of Polygnotos, in both typically barbarian garb and in Greek armor: cf. in particular London 1899,0721.5 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1052.29; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 213658). For a full discussion of Amazons within the Group, which seems to have had a particular proclivity for such scenes, see Abbreviation: Matheson, PolygnotosS. B. Matheson. Polygnotos and Vase Painting in Classical Athens. Madison, Wisc., 1995, 234–44. Polygnotan Amazons typically wear patterned, long-sleeved shirts, close-fitting trousers, and soft leather shoes tied in front, like the figure at the left on Princeton’s krater: cf. Syracuse 23507 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1032.53; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 213436). It is impossible to tell, however, given the position of the shield, whether Princeton’s figure wears a short jacket or sleeveless vest typical of the Group’s Amazons. As for the figure to the right, who wears Greek armor, cf. London 1898,0715.1 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1048.35; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 213604). Although often shown in battle, mounted Amazons do occur in scenes within the Group of Polygnotos in which they seem to be journeying to or preparing for a battle, as is the case on Princeton’s krater: e.g., Ferrara 3089 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1029.21; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 213403). For a discussion of mounted Amazons in Early Classical and Classical vase-painting, beyond the Group of Polygnotos, see D. von Bothmer, Amazons in Greek Art (Oxford, 1957), 175–84. For a discussion of the relationship between the scenes on Polygnotan vases and the monumental mural painting of the Amazonomachy by Mikon in the Stoa Poikile, see Bothmer, Amazons, 161–74; J. Boardman, “Herakles, Theseus, and Amazons,” in The Eye of Greece: Studies in the Art of Athens, eds. D. Kurtz and B. Sparkes (Cambridge, UK, 1982), 1–28.

The clothing and armor of the figures on side B show a rare combination of Thracian caps with Greek armor: greaves in the case of the figure at the left and a cuirass for the middle figure. Although this kind of skin cap is commonly called an alopekis (fox skin), foxes do not have striped tails, leading some to suggest that they are instead the skins of a species of wild cat; see J. M. Padgett, “Phineus and the Boreads on a Pelike by the Nausicaa Painter,” Abbreviation: JMFAJournal of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 3 (1991): 22. A fragment of a krater from Camarina attributed to the Villa Giulia Painter, whom Philippaki has linked with the Group of Polygnotos (B. Philippaki, The Attic Stamnos [Oxford, 1967], 151), shows a warrior wearing a foreign cap and a cuirass as he puts on greaves: G. Giudice, ed., “Ἀττικὸν . . . κέραμον”: Veder Greco a Camarina; Dal principe di biscari ai nostri giorni (Catania, 2010), 1: 96–97, no. I 37. Scenes of arming very often contain the motif of a warrior lifting his leg to strap on a greave, although this is more commonly seen in the Late Archaic period and tends to be displaced from the mid-fifth century onward by the motif of the donning of the helmet. As on Princeton’s krater, the warriors in arming scenes of the mid-fifth century are most often beardless: see Osborne, Transformation, 109–11.