Provenance

1970, sale, La Reine Margot (Paris) to Jean Michel Robert (Dijon); 2007, sale, Jean Michel Robert to La Reine Margot; 2007, sale, Royal-Athena Galleries (New York, NY) to Princeton University.

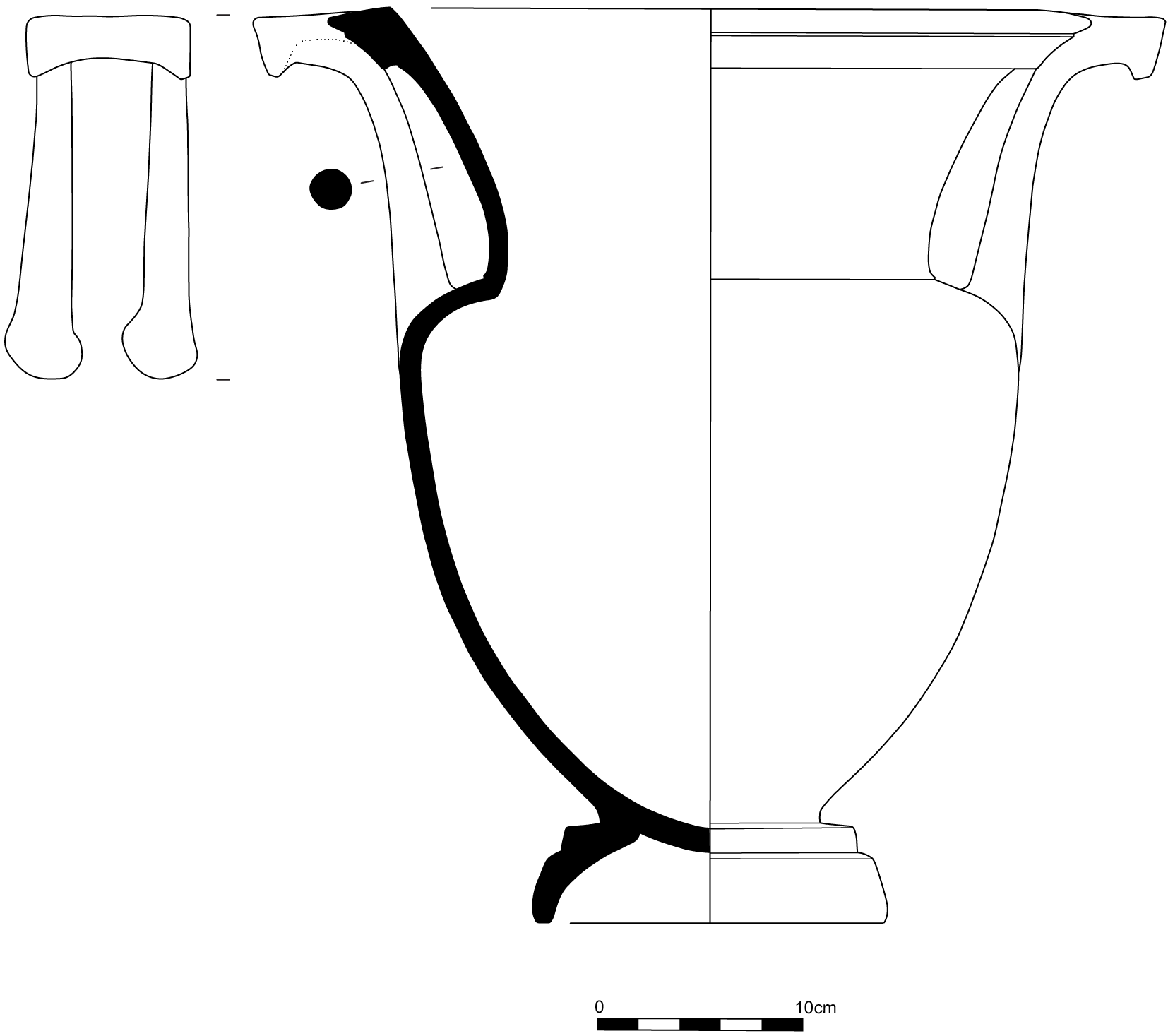

Shape and Ornament

Top of rim black and convex; vertical overhang flaring outward at the juncture with upper surface. Interior of rim and neck black. Laurel wreath with berries on either side of the rim. Flat handle plate extending beyond the rim at each side supported by two black “columns.” Each handle root nearly encircled by a slender, reserved crescent. Atop each handle plate a pair of stacked, red-figure palmettes, the lower one enclosed by tendrils that spiral up to frame the smaller one above. Frieze of pendant lotus buds on both sides of neck; neck black behind each handle. Ovoid body, interior streaky black. Figural panels on body framed above by black tongues, laterally by slender, vertical bands of black and reserved chevrons. In each panel the groundline is a band of stopt meanders in groups of one to five, separated by checkerboards. Molded foot in two degrees—black torus and reserved riser—the reserved underside hollow and domed, with narrow resting surface (w. 0.5 cm).

Subject

A. Wheeling chariot. A pair of figures—driver and passenger—are conveyed to the left in a wheeling chariot drawn by four horses. The legs of the horses are all raised in unison, as though flying over the landscape, the latter indicated by five small plants. The horses’ bodies are in three-quarter view, as are their heads, except for that of the left trace horse, which is in profile. Their mouths are open, their teeth gnashing at the bits, which are textured with applied clay pellets. They wear broad breast-bands and bridles with circular disks. The ears are quite small, the manes clipped short and tinted with dilute gloss. The tail of the trace horse at right is the only one visible; its upper half is plump and reserved, but its long, lower half, which extends across the passenger’s body, is drawn with strands of brown diluted gloss.

The front of the chariot is decorated with a figural scene, part of which is visible to the left of the wheel, where it disappears behind the horses: the leg and swirling, patterned chitoniskos of a human figure in action, possibly in a fight. The passenger is a bearded man who rests a pair of spears on his left shoulder and grasps the rail with his right hand. His head is in profile to the left, his long brown hair visible beneath a felt or leather cap of oriental design, whose long flaps trail in the wind. The curling peak of the cap is lined with spiky protrusions, like the fins of a ketos (sea monster). The cap and spears overlap the frames of the figure panel. Reinforcing the man’s identification as a barbarian is his long-sleeved tunic, woven with zigzag patterns. Over this he wears a long robe, a fuller version of the Persian kandys, decorated with long rays, zigzags, and bands of undulating ketea, a popular textile design of the period, not exclusive to garments of eastern origin. As a final accessory he wears a short, black-hemmed cloak of Greek design—a chlamys—pinned with a circular brooch.

The charioteer holds the reins in his left hand and wields a goad in his right. He, too, wears a sleeved undergarment with zigzag patterns, and a spiky Phrygian cap decorated with flowers. Instead of a kandys, there is what appears to be a short vest, perhaps a chest protector, below which emerge the folds of a long, belted chiton—appropriate garb for a charioteer. The driver’s beardless face, delicate features, and long hair, which falls well past the shoulders, raise the possibility that the person might be a woman (infra).

The third figure in the scene, at the far left, has hair and features very like those of the driver. Placed beyond the hooves of the farthest trace horse, he is not being trampled, but seems rather to run alongside it. He looks back at the chariot and flings his left arm toward it. His body is frontal, but his right leg is raised in profile to the left, not only overlapping the frame of the panel but also nearly stepping out of it. He holds a war hatchet in his right hand. He, too, is dressed in full barbarian regalia: Phrygian cap, patterned trousers, sleeved tunic, and a billowing, belted kandys, richly woven with waves, palmettes, and bands of ketea. Like the bearded man, he too has a short cloak over his left arm.

B. Three mantle figures Two beardless youths stand on either side of a third boy, slightly shorter, who faces the youth at right. Their postures are relaxed, the right legs flexed and advanced. All three wear himatia, the central boy’s swathing him entirely and pulled taut by his right arm. The youth at right holds a stick in his right hand, resting it vertically on the ground. The youth at left holds out a strigil in his right hand. Hanging between the two right-hand figures is a diskos with a cross. The drawing is cursory, the drapery lines faint and sketchy.

Attribution and Date

Attributed to the Suessula Painter [J. M. Padgett]. Circa 405–400 BCE.

Dimensions and Condition

h. 42.5 cm; w. 44.6 cm; diam. of mouth 37.2 cm; diam. of foot 17.2 cm. Repaired from mostly large fragments, with inpainted cracks. Two-thirds of the rim on side B is restored, including the center and most of the right half of the wreath. Parts of all four handles are restored. On the body, most lacunae are small and confined to the black ground: e.g., immediately left and right of the panel on side A, and before the face of the charioteer, whose cap is restored with a coiled peak that originally was probably spiked. The rim of side A is chipped, and there are smaller chips and scratches throughout. Areas of misfiring on side B have been tinted matte black. The reserved undersides of the handle plates are smeared with gloss. There are multiple drill holes from an ancient repair, most notably a triangular trio on the two horses at left, a pair below the butts of the bearded man’s spears, and a pair between the first and second youths on side B; other drill holes circle the lower body above the unbroken foot.

Technical Features

Preliminary sketch: a few indications on side A; e.g., above the bearded man’s eye. Relief contours: throughout on side A, except for short passages (cloaks draped over arms). Accessory color. White: on side A, dots on the caps of the bearded man and the running warrior. Dilute gloss: on side A, hair of all three figures; manes, irises, and selected muscle lines of the horses, and the tail of the horse at right; zigzag patterns on garments. Applied relief: tiny black pellets on the horses’ bits.

Bibliography

Royal-Athena Galleries, Art of the Ancient World XIX, auc. cat. (New York, NY, 2008), no. 128 [detail on cover]; Abbreviation: Princeton RecordRecord of the Princeton University Art Museum. (1942– ). 67 (2008): 116–17 [illus.]; J. M. Padgett, “Whom are You Calling a Barbarian? A Column-Krater by the Suessula Painter,” in Abbreviation: Athenian Potters and PaintersAthenian Potters and Painters: The Conference Proceedings. 3 vols. Vol. 1, edited by J. H. Oakley, W. D. E. Coulson, and O. Palagia. Oxbow Monograph 67. Vol. 2, edited by J. H. Oakley and O. Palagia. Vol. 3, edited by J. H. Oakley. Oxford, 1997 (vol. 1), 2009 (vol. 2), 2014 (vol. 3), vol. 3, 146–54; A. Mayor, The Amazon: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World (Princeton, NJ, 2014), 178, fig. 11.1; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 9022226.

Comparanda

For the Suessula Painter, see Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1344–46, 1691; Abbreviation: ParalipomenaJ. D. Beazley. Paralipomena: Additions to Attic Black-Figure Vase-Painters and to Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. Oxford, 1971 482; Abbreviation: BAdd2Carpenter, T. H., ed. 1989. Beazley Addenda: Additional References to ABV, ARV2, and Paralipomena. 2nd ed. Oxford: Published for the British Academy by Oxford University Press. 367–68; I. D. McPhee, “Attic Vase-Painters of the Late 5th Century B.C.” (PhD diss., University of Cincinnati, 1973), 161–207; Padgett, “Whom are You Calling a Barbarian?” The Suessula Painter was active in the last decade of the fifth century, alongside other exemplars of the Ornate Style, such as the Talos Painter and the Semele Painter, all of them within the larger ambit of the Pronomos Painter. The chariot and horses in Princeton recall those on the painter’s masterpiece in Paris (Paris, Louvre S 1677: Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1344.1, 1691; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 217568), a neck-amphora with twisted handles decorated with a Gigantomachy that von Salis convincingly associated with the painting of this subject on the interior of the shield of Phidias’s statue of Athena Parthenos: A. von Salis, “Die Gigantomachie am Schilde der Athena Parthenos,” Abbreviation: JdIJahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 55 (1940): 90–169. The figures on the reverse, particularly the youth holding a stick, have correspondents in two of the artist’s column-kraters: London E 490 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1345.7; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 217574); Madrid 11045 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1345.8; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 217575).

Including the Princeton vase, Padgett (“Whom are you Calling a Barbarian?”) has attributed three new column-kraters to the Suessula Painter, and Giudice has added a fourth with a “Persian symposium”: Salerno T 228 (G. Giudice, Il tornio, la nave e le terre lontane: Ceramografici attici in Magna Grecia nella seconda metà del V sec. a.C.; Rotte e vie di distribuzione [Rome, 2007], 208, fig. 203, no. 430; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 375). These additions make the shape the painter’s favorite. Indeed, by the end of the fifth century, the Suessula Painter and the Meleager Painter were the only painters of note who decorated column-kraters in any numbers; in the next generation, the shape disappeared from the Attic repertory. The design of the Princeton krater exhibits a certain refinement, its “columns” arcing gracefully into the line of the overhanging rim, but the actual potting is slipshod, the neck on side B slumps to one side, so that the rim is higher in front. Much of the ornament—tongues, meanders, handle palmettes—is executed with a clumsiness at variance with the careful drawing of the chariot scene. The wreaths on the rim and the use of chevrons as panel frames are both unusual features, the latter recurring on the reverse of another, even larger column-krater in the Conradty Collection: E. Simon, ed., Mythen und Menschen: Griechische Vasenkunst aus einer deutschen Sammlung (Mainz, 1997), 140–44, no. 39. Kathariou has identified the reverse of the Conradty krater as an early work by the Meleager Painter, while instead assigning the Amazonomachy on the obverse to the Painter of the New York Centauromachy, an artist otherwise not known to have decorated this shape: Abbreviation: Kathariou, Ergastērio Z. tou MeleagrouK. Kathariou. To ergastērio tou Zografou tou Meleagrou kai hē epochē tou: Paratērēseis stēn attikē keramikē tou protou tetartou tou 4ou ai. p. Chr. Thessaloniki, 2002, 191, 213, 389, fig. 9, no. MEL 14.

The lotus buds on either side of the neck of the Princeton krater are curiously pinched and attenuated in their lower extremities, something that apparently occurs only on column-kraters by the Suessula Painter. They appear on another, smaller column-krater by the artist, which depicts Eros driving the chariot of Aphrodite: Naples 146740 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1345.9; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 217576). On the Naples krater, the framing ornament is the usual ivy, but the leaves are curiously flattened and stylized, ranging in shape from a Y to a T; one sees them again on the painter’s column-kraters in London (supra) and Madrid (supra), and in combination with attenuated lotus buds on three of the column-kraters attributed by Padgett and Giudice. One of the latter, in the Spanish market, features a departure scene in which all three figures wear Thracian garments, and thus provides another instance, like the “Persian symposium” in Salerno (supra), of the artist casting barbarian protagonists in an otherwise familiar Greek tableau: see Padgett, “Whom are you Calling a Barbarian?,” 149.

The identities of the figures on side A are unclear. In another context, the hatchet-wielding warrior might be identified as an Amazon: cf., by Aison, an Amazon in a similar stance on Naples RC 239 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1174.6; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 215562). The charioteer, however, is essentially identical in appearance, and while Amazons are great riders, they are only rarely represented as charioteers: e.g., by the Niobid Painter, Naples H 2421 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 600.13; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 206941). There are none at all after the mid-fifth century, nor one in any period who is accompanied by a male passenger, let alone a bearded barbarian. Female charioteers abound late in the century, but they are always Nike or one of the Olympian goddesses, as Aphrodite drives the chariot of Ares in the Gigantomachy on the Suessula Painter’s neck-amphora in the Louvre (supra). Since the Princeton charioteer cannot be an Amazon, the foot soldier may not be one either, leading Padgett to conclude that both are males. He pointed to a neck-amphora by the Suessula Painter with a young Greek warrior whose features are no less delicate—and whose tresses are no less lengthy—than those of the Amazon before him: New York 44.11.12 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 344.3; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 217570). The beardless young Persians gathered at supper on the artist’s bell-krater in Salerno (supra) are even more to the point, and Padgett noted other late fifth-century vases with bearded Persians accompanied by beardless young huntsmen in barbarian garments; e.g., Naples H 3251 (Padgett, “Whom are you Calling a Barbarian?,” 151, fig. 9; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 2568). Many male deities and heroes take to a chariot, but only a few were of foreign birth and thus liable to be represented in such clothing. On a fourth-century lekythos in the Hermitage, for example, Paris prepares to drive off with his bride Helen, but it is he who holds the reins: St. Petersburg ST 1929 (Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 6554).

Padgett’s suggestion (“Whom are You Calling a Barbarian?,” 151–52), here repeated, is that the bearded barbarian on the Princeton krater may represent Pelops. Pindar specifies that Pelops was from Lydia (Ol. 1, 24), but most other ancient authors placed his home in Phrygia: see I. Tirnatis, in Abbreviation: LIMCLexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae. 1981–2009 7 (1994), 282–87, pls. 219–23, s.v. “Pelops”; M. C. Miller, “Barbarian Lineage in Classical Greek Mythology and Art: Pelops, Danaos and Kadmos,” in Cultural Borrowings and Ethnic Appropriations in Antiquity, ed. E. S. Gruen (Stuttgart, 2005), 70–75. For a century after his first appearance in Attic vase-painting, Pelops was represented no differently from other Greek heroes, but on a kalpis attributed to Polygnotos, he is shown dressed in a patterned gown and Phrygian cap, and driving the chariot drawn by the winged steeds that Poseidon had given him: Ferrara 3058 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1032.58, 1679; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 213441). On the name-vase of the Oinomaos Painter, a bell-krater painted roughly a decade after the Princeton krater, Oinomaos sacrifices before the race: Naples H 2200 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1440.1; Padgett, “Whom are you Calling a Barbarian?,” 151, fig. 10; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 218098). His charioteer, Myrtilos, wearing a Greek chiton, brings up the king’s chariot, while Pelops and Hippodameia stand beside one another in their own chariot. Pelops is represented wearing rich oriental garments, complete with a sleeved tunic and spiky Phrygian cap, and one wonders whether he appeared on stage in similarly exotic garb in Euripides’s play, Oinomaos, produced in 409 BCE.

Like Oinomaos, Pelops, too, had a charioteer, who did not live to accompany his master to Pisa. His name was Killas, also known as Sphaeros: see P. Müller, in Abbreviation: LIMCLexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae. 1981–2009 6 (1992), 47, pl. 66, s.v. “Killas.” No depiction of Killas in vase-painting has been identified, but Pausanias (5.10.7) was told that he appeared, with Pelops, on the east pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. The kneeling figure from the pediment that is sometimes identified as Killas is in Greek dress: B. Ashmole and N. Yalouris, Olympia: The Sculptures of the Temple of Zeus (London, 1967), 16, pls. 55–57. In the pediment, Pelops is also wearing Greek attire, but in a vase-painting from the end of the century we would expect that, as Easterners, both men would be depicted in barbarian costume. One reason that we would not expect Killas’s presence on the Olympia pediment is that, according to the fourth-century historian Theopompos, Pelops set off for Olympia with Killas at the reins, but as the winged steeds flew over the straits toward Lesbos, Killas was thrown and killed (Theopomp. FGrHist 115 F 350). Padgett speculated that the Princeton krater shows Pelops and Killas departing for Greece, and that the choice of this unusual subject may have been prompted by contemporary events in Athens.

Robertson (Abbreviation: Robertson, Art of Vase-PaintingM. Robertson, The Art of Vase-Painting in Classical Athens. Cambridge, 1992, 258–59) argues that the better works of such ostensibly later artists as the Painter of the New York Centauromachy were actually produced just before the end of the century; e.g., that painter’s Amazonomachy in the Conradty Collection (supra). Behind this brief fashion for mythological extravaganzas Robertson recognizes the patronage of the Thirty Tyrants, the pro-Spartan regime that took power in Athens in 403 BCE, pointing in particular to a trio of complete and fragmentary bell-kraters that Beazley thought were connected both with the Semele Painter and (less closely) the Suessula Painter. Among them are a bell-krater with Leda and the Egg (S. Agata de’ Goti, Mustilli Collection: Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1344.1; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 217565), and an unnumbered fragment from the Athenian Kerameikos that likely shows one of the Dioskouroi from a scene with the same Laconian subject (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1344.3; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 217567). The fragment was found in or near the Tomb of the Lacedaemonians who fell in 403, and a clear argument can be made for a distinctly Laconian–Theban strain in many of the finer vases from the end of the century; for the Laconian influence, see M. Tiverios, “The Cadmus Painter and His Time,” in “Ἀττικον . . . κέραμον”: Veder greco a Camarina; Dal principe di biscari ai nostri giorni, eds. G. Giudice and E. Giudice (Catania, 2011), 2: 171–72. Among Theban themes there is the birth of Dionysos on the name-vase of the Semele Painter (Berkeley 8.3316: Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 343.1, 1681, 1691; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 217563) and the Theban musician Pronomos on the name-vase of the Pronomos Painter (Naples 81673: Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1336.1, 1704; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 217500). More tellingly, it has been proven that the Suessula Painter himself worked briefly in Corinth, decorating a locally made bell-krater, suggesting that he might himself be Corinthian by birth or politics: Corinth C. 37-447 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1345.13; S. Herbert, The Red-figure Pottery, Corinth 7, Part 4 [Princeton, NJ, 1977], 47–48, no. 76, pl. 13; E. G. Pemberton, “Athens and Corinth: Workshop Relations in Stamped Black-Glaze,” in Abbreviation: Athenian Potters and PaintersAthenian Potters and Painters: The Conference Proceedings. 3 vols. Vol. 1, edited by J. H. Oakley, W. D. E. Coulson, and O. Palagia. Oxbow Monograph 67. Vol. 2, edited by J. H. Oakley and O. Palagia. Vol. 3, edited by J. H. Oakley. Oxford, 1997 (vol. 1), 2009 (vol. 2), 2014 (vol. 3), vol. 1, 415, fig. 26, 416–17; I. D. McPhee and E. Kartsonaki, “Red-Figure Pottery of Uncertain Origin from Corinth: Stylistic and Chemical Analyses,” Abbreviation: HesperiaHesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens 79 [2010]: 124, fig. 10, 125, 136; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 217580).

The Persians and the Spartans were closely allied at the conclusion of the Peloponnesian War, and it is possible that a partisan of the Thirty Tyrants and the pro-Spartan party at Athens may have commissioned a work indirectly celebrating their alliance, with a depiction of Pelops—whom Herodotus has Xerxes himself evoke as a forebear (Hdt. 7.11)—with his charioteer, Killas, setting out for Greece.