Provenance

Fragment 1: By 1972, Cornelius C. Vermeule III and Emily T. Vermeule (Fragment 1 lent by the Vermeules to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, on Feburary 4, 1972 [loan 49.1972]); by 1976, Emily Dickinson Blake Vermeule (Fragment 1 was described by Buitron [infra] as being in the collection of Blake Vermeule); 2002, gift, Cornelius C. Vermeule III to Princeton University.

Fragment 2: By 1976, Emily Dickinson Blake Vermeule (Fragment 1 was described by Boardman [infra] as being in the collection of Blake Vermeule); 2002, gift, Cornelius C. Vermeule III to Princeton University.

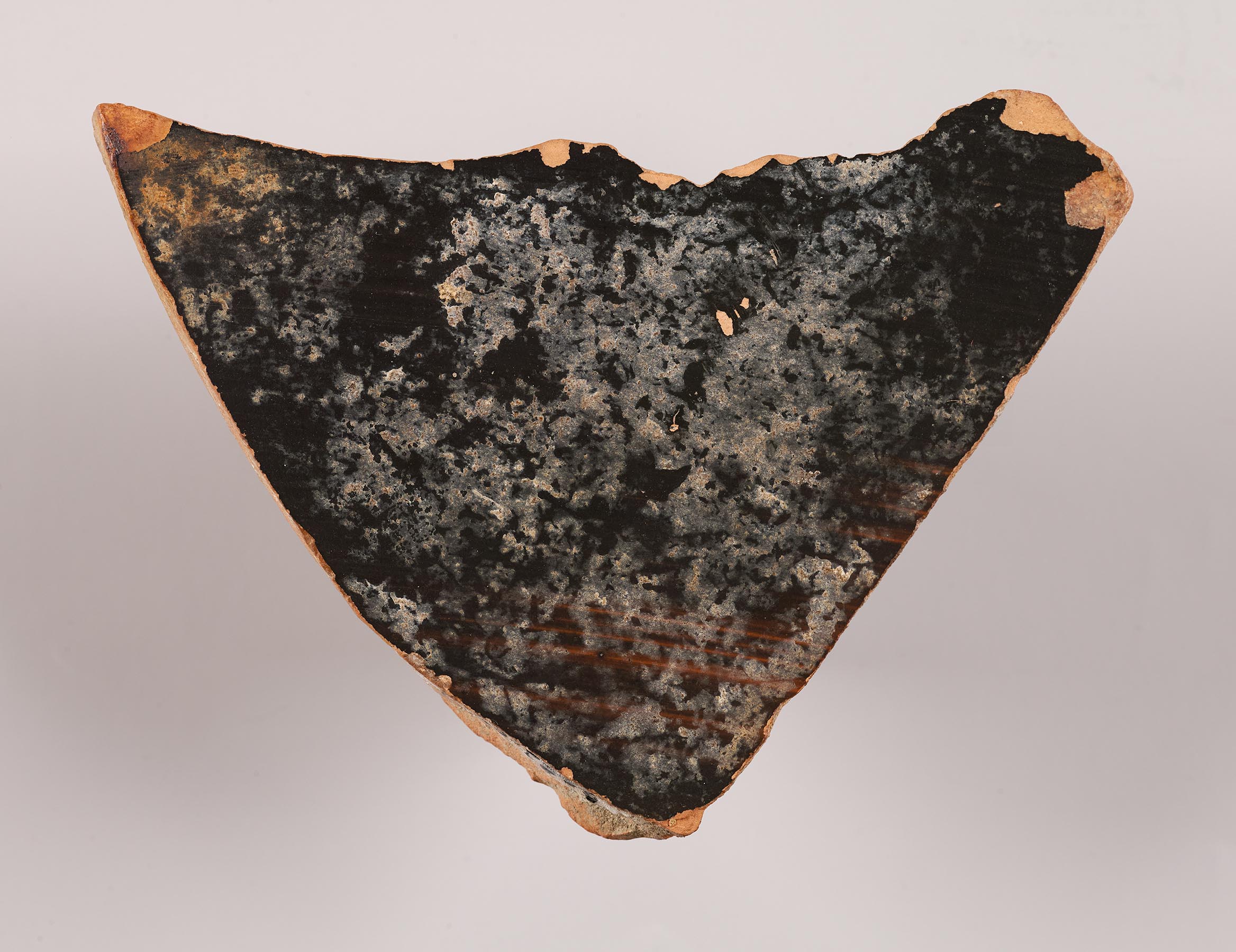

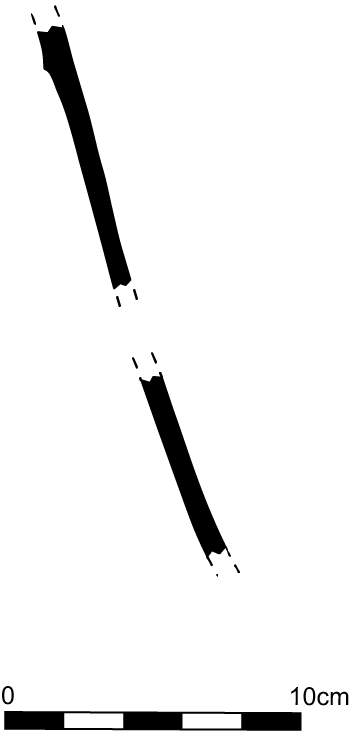

Shape and Ornament

Fragment 1 from offset rim, preserving coiling tendrils of an enclosed, upright palmette, with elliptical bud at lower right. Horizontal reserved band near the top of black interior. Interior of Fragment 2, from lower on body, also black.

Subject

Grave mound of Achilles and Patroklos. The two nonjoining fragments preserve parts of a tall burial tumulus on and before which are arrayed a panoply of arms: helmet, cuirass, greaves, shield, bow, spear. The tumulus is tinted with a wash of miltos (reddish ocher), while the objects are reserved in the paler clay of the vessel.

Fragment 1 preserves the top of the mound, where an elaborately decorated helmet, facing left, is mounted on a post and baseplate supported on two protruding pegs. Two objects are suspended from a third peg at upper left: a bow (?) with a relief-line string, the tip of which is visible, hangs from a red cord, while a thicker red strap supports another, missing object (infra). The area between the bow and its string is not tinted with miltos, an apparent oversight. The helmet is essentially of Corinthian type, but with cutouts for the ears and notches in the front of the cheek pieces to leave the mouth free. The cheek piece is clearly hinged, as on an Attic helmet, but there is no vizor. The crown of the helmet is adorned with scale pattern, the scales alternately black and reserved, the latter tinted with miltos. The lower part of the helmet is black, with a reserved band edging the perimeter from nape to nose. A relief line—black on black—defines the eyebrow. The cheek piece is decorated with a tight coil consisting of tiny incised circles; the black nape guard is incised with scale pattern. A double band of black dots defines the lower edge of the reserved horsehair crest, in the middle of which is a faint row of tiny crescents in dilute gloss. Immediately below the helmet is part of a black shield with a reserved rim speckled with dots of dilute gloss.

Fragment 2 is from the lower left side of the tumulus. Just to the left of the mound’s steep contour is the shaft of a spear, presumably fixed in the ground. The tumulus stands on a reserved base, untinted, on which sit—side by side and touching—a pair of greaves and a bronze muscle cuirass. The cuirass has deeply hooked clavicles, coiled pectorals, and modeled ribs. In the center, barely visible, a small palmette in dilute gloss springs from the juncture of the coils.

At least thirty-six unpublished fragments from the same krater are in Atlanta in the Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University (2006.51.11). Among them are two sherds formerly on the New York art market that Padgett recognized in 1993 as being from the same vase as the Vermeule fragments, including one with traces of burning that joined and completed the helmet on what is now Princeton’s Fragment 1. The second sherd revealed that the shield on the tumulus featured a red-figure device in the form of a lion standing to the left on an ovolo groundline. Two other fragments at Emory, one of them burned, give more of the lion. One of these preserves the lower end of the sword that hung from the red strap on Princeton’s Fragment 1, the scabbard wrapped with a snake and the black chape incised with a Macedonian star. Fragment 2 in Princeton joins a group of four joining fragments at Emory that nearly completes the cuirass. On the same fragment is the right contour of the tumulus, which is almost twice as tall as it is wide. To the right of the cuirass a sponge, aryballos, and strigil hang on the tinted mound. A himation dangles to the right of the mound, and another Emory fragment gives part of a second draped figure on the left side, along with a portion of the spear there. Below the tumulus, three fragments at Emory preserve a stretch of the groundline, consisting of linked meanders to left; on the other side, these are replaced with a simpler key pattern. The subject of the reverse was apparently arming, with bustling warriors and a shield being taken from its cloth bag. There were black tongues above the krater’s foot and large palmettes above the handles. In plate 25, Fragments 1 and 2 are shown in a collage approximating their position relative to the fragments at Emory; there are other small pieces at Emory that also may be from the same side.

Attribution and Date

Attributed to the Kleophrades Painter [D. von Bothmer/J. Boardman]. Circa 500–490 BCE.

Dimensions and Condition

Fragment 1: h. 9.2 cm; w. 4.6 cm; thickness: rim 0.8 cm; wall 0.5–0.6 cm.

Fragment 2: h. 7.2 cm; w. 9.5 cm; thickness 0.6–0.7 cm.

Both fragments broken on all sides. Good surface condition; minor chipping on baldric and bow. Film of white incrustation on the interior of Fragment 2.

Technical Features

Relief contours throughout, except the inner coils of the rim palmette. Accessory color. Red: bow cord; sword baldric. Dilute gloss: palmette on cuirass; crescents on helmet crest; dots on shield rim. Miltos wash: tumulus; reserved helmet scales. Incision on coil on helmet cheekpiece and scales on nape guard.

Bibliography

D. M. Buitron, Attic Vase Painting in New England Collections, exh. cat., Fogg Art Museum (Cambridge, MA, 1972), 82, no. 38 (Fragment 1 only); J. Boardman, “The Kleophrades Painter at Troy,” Abbreviation: AntKAntike Kunst 19 (1976): 6–7, no. 14, pl. 2.2; A. Jiang, “The Kleophrades Painter and His World” (PhD diss., Emory University, 2019), 213–15, 357, no. E13, fig. 131; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 3197.

Comparanda

D. von Bothmer, initially knowing only Fragment 1, noted that the palmette was Kleophradean: von Bothmer, quoted in Buitron, New England Collections, 82. Boardman (“Kleophrades Painter at Troy,” 6), who also saw Fragment 2, said the pair were “probably” by the Kleophrades Painter. The attribution was confirmed by von Bothmer when, over three decades, he acquired for his personal collection additional fragments, which he subsequently donated to Emory in 2006. For the Kleophrades Painter, see Abbreviation: ABVJ. D. Beazley. Attic Black-Figure Vase-Painters. Oxford, 1956 404–5, 696, 715; Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 181–95, 1631–33, 1705; Abbreviation: ParalipomenaJ. D. Beazley. Paralipomena: Additions to Attic Black-Figure Vase-Painters and to Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. Oxford, 1971 175–76, 340–41; Abbreviation: BAdd2Carpenter, T. H., ed. 1989. Beazley Addenda: Additional References to ABV, ARV2, and Paralipomena. 2nd ed. Oxford: Published for the British Academy by Oxford University Press. 105, 186–89; J. D. Beazley, “Kleophrades,” Abbreviation: JHSJournal of Hellenic Studies 30 (1910): 38–68; id., “Two Vases in Harrow,” Abbreviation: JHSJournal of Hellenic Studies 36 (1916): 123–33; id., The Kleophrades Painter (Mainz, 1974); G. M. A. Richter, “The Kleophrades Painter,” Abbreviation: AJAAmerican Journal of Archaeology 40 (1936): 100–115; R. Lullies, Die Spitzamphora des Kleophrades Malers (Bremen, 1957); Beazley, “A Hydria by the Kleophrades Painter,” Abbreviation: AntKAntike Kunst 1 (1958): 6–8; A. Ashmead, “Fragments by the Kleophrades Painter from the Athenian Agora,” Abbreviation: HesperiaHesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens 35 (1966): 20–36; U. Knigge, “Neue Scherben von Gefässen des Kleophrades-Malers,” Abbreviation: AMMitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung 85 (1970): 1–22; Abbreviation: Greifenhagen, Neue Fragmente des KleophradesmalersA. Greifenhagen. Neue Fragmente des Kleophradesmalers. Sitzungberichte der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften. Philosophisch-historische Klasse, Jahrgang 1972, 4. Abhandlung. Heidelberg, 1972; Boardman, “The Kleophrades Painter’s Cup in London,” Abbreviation: GettyMusJThe J. Paul Getty Museum Journal 1 (1974): 7–14; F. W. Hamdorf, “Eine neue Hydria des Kleophradesmalers,” Pantheon 32 (1974): 219–24; Boardman, “Kleophrades Painter at Troy”; J. Frel, “The Kleophrades Painter in Malibu,” Abbreviation: GettyMusJThe J. Paul Getty Museum Journal 4 (1977): 63–76; Boardman, “Epiktetos II, R.I.P.,” Abbreviation: AAArchäologischer Anzeiger (1981): 329–31; von Bothmer, “'΄Aμασις, 'Αμάσιδος,” Abbreviation: GettyMusJThe J. Paul Getty Museum Journal 9 (1981): 1–4; M. Robertson, “Fragments of a Dinos and a Cup by the Kleophrades Painter,” in Abbreviation: GkVasesGetty 1Frel, J., and S. K. Morgan, eds. 1983. Greek Vases in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Occasional Papers on Antiquities 1. Malibu: J. Paul Getty Museum., 51–54; S. B. Matheson, “Panathenaic Amphorae by the Kleophrades Painter,” in Abbreviation: GkVasesGetty 4True, M., ed. 1989. Greek Vases in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Vol. 4. Occasional Papers on Antiquities 5. Malibu: J. Paul Getty Museum., 95–112; F. Lissarrague, “Un peintre de Dionysos: Le peintre de Kleophrades,” in Dionysos, mito e mistero: Atti del convegno internazionale, commachio 3–5 novembre 1989, ed. F. Berti (Ferrara, 1991), 257–76; Abbreviation: Kunze-Götte, Der Kleophrades-MalerE. Kunze-Götte. Der Kleophrades-Maler unter Malern schwarzfigurigen Amphoren. Mainz, 1992; Abbreviation: Robertson, Art of Vase-PaintingM. Robertson, The Art of Vase-Painting in Classical Athens. Cambridge, 1992, 56–68; D. Williams, “From Pelion to Troy: Two Skyphoi by the Kleophrades Painter,” in Abbreviation: Athenian Potters and PaintersAthenian Potters and Painters: The Conference Proceedings. 3 vols. Vol. 1, edited by J. H. Oakley, W. D. E. Coulson, and O. Palagia. Oxbow Monograph 67. Vol. 2, edited by J. H. Oakley and O. Palagia. Vol. 3, edited by J. H. Oakley. Oxford, 1997 (vol. 1), 2009 (vol. 2), 2014 (vol. 3), vol. 1, 195–201; L. Cerchiai, “L’hydria Vivenzio di Nola,” in Il Greco, il barbaro e la ceramica attica, eds. F. Giudice and P. Pavini (Rome, 2006), 3:39–45; B. Kreuzer, “An Aristocrat in the Athenian Kerameikos: The Kleophrades Painter = Megakles,” in Abbreviation: Athenian Potters and PaintersAthenian Potters and Painters: The Conference Proceedings. 3 vols. Vol. 1, edited by J. H. Oakley, W. D. E. Coulson, and O. Palagia. Oxbow Monograph 67. Vol. 2, edited by J. H. Oakley and O. Palagia. Vol. 3, edited by J. H. Oakley. Oxford, 1997 (vol. 1), 2009 (vol. 2), 2014 (vol. 3), vol. 2, 116–24; Jiang, “Kleophrades Painter.”

Numerous details are paralleled on works by the Kleophrades Painter. For the rim palmette, cf. those on the calyx-kraters Paris, Louvre G 48 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 185.33, 1632; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 201685); Harvard 1960.236 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 185.31; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 201683). The artist often used a key pattern for groundlines, as on the Harvard krater (supra). On the calyx-krater Tarquinia RC 4196 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 185.35, 1632; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 201687)—which has black tongues above the foot—it is again employed on only one side. For the shape of the helmet, cf. a volute-krater fragment in Paris: Paris, Cab. Méd. 863 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 187.53; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 201705). For the helmet’s two-toned imbrication, cf. a helmet next to a tumulus on a calyx-krater fragment attributed by Williams to the Kleophrades Painter: Aegina, Archaeological Museum (E. Walter-Karydi, W. Felten, and R. Smetana-Scherrer, Ostgriechische Keramik, lakonische Keramik, attische schwarzfigurige und rotfigurige Keramik, spätklassische und hellenistische Keramik, Alt-Ägina 2, 1 [Mainz, 1982], 34–35, 48, no. 283, pl. 21; Williams, “From Pelion to Troy,” 200). For the unoccupied greaves, cf. the freestanding one in an arming scene on the pointed amphora Berlin 1970.5 (Abbreviation: Greifenhagen, Neue Fragmente des KleophradesmalersA. Greifenhagen. Neue Fragmente des Kleophradesmalers. Sitzungberichte der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften. Philosophisch-historische Klasse, Jahrgang 1972, 4. Abhandlung. Heidelberg, 1972, pl. 11.3–4; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 5766), and the pair in a portable frame carried by a satyr on the neck-amphora Harrow 55 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 183.11; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 201664). The muscle cuirass has the hooked clavicles of the Kleophrades Painter’s early style, but is otherwise an anomaly. The only other example of such a corselet by the artist is worn by an Amazon on the fragment Paris, Louvre G 166A (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 186.51, 206.130; Abbreviation: Greifenhagen, Neue Fragmente des KleophradesmalersA. Greifenhagen. Neue Fragmente des Kleophradesmalers. Sitzungberichte der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften. Philosophisch-historische Klasse, Jahrgang 1972, 4. Abhandlung. Heidelberg, 1972, pl. 15; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 201703), which is now incorporated in the volute-krater Malibu 77.AE.11. Boardman (“Kleophrades Painter’s Cup in London,” 8) points to several examples of snake-wrapped scabbards by the artist, but the hooked helmet-holders that he enumerates elsewhere (“Kleophrades Painter at Troy,” 6 n. 19) differ from the mount on Fragment 1. For the sponge and aryballos, cf. those on the early hydria Salerno 1371 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 188.67; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 201759). The red-figure shield device is unusual in the painter’s ouevre, but the stance of the lion is identical to one in black silhouette—also on a groundline—on the neck-amphora fragment Florence 8 B8 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 189.82 [as 8 B6]; G. Rocco, J. Gaunt, M. Iozzo, and A. Paul, Ceramica attica bilingue a figure rosse e vernice nera. La Collezione Astarita nel Museo Gregoriano Etrusco 2.2 [Vatican City, 2016], 87–90, no. 59, pl. 63; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 201730). For a shield being taken from its bag, cf. Paris, Cab. Méd. 420 A (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 185.37; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 201689).

Given the prominence of the armor, Boardman (“Kleophrades Painter at Troy,” 6) speculated that the tumulus was that of Achilles, whose panoply became a bone of contention and was commonly depicted in this period in scenes of the Greeks voting about its disposition: see N. Spivey, “Psephological Heroes,” in Ritual, Finance, Politics: Athenian Democratic Accounts; Presented to David Lewis, eds. R. Osborne and S. Hornblower (Oxford, 1994), 39–52. Williams (“From Pelion to Troy,” 200) and Jiang (“Kleophrades Painter,” 214–15) agree, the former evoking the fragments now at Princeton and Emory in suggesting that the subject of the krater fragment from Aegina (supra), with a shield and two helmets piled around a tumulus, was the Greeks mourning at the tomb of Achilles before voting on the armor. The presence of two helmets reminds us that the tomb is also that of Patroklos, with whose ashes those of Achilles were mixed. In a depiction of the sacrifice of Polyxena, Makron represented what is certainly their tomb, its rounded mass again on a prominent base: Paris, Louvre G 153 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 460.14, 481; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 204695). Makron’s mound is also decked with both martial and athletic equipment—sword, diskos, sponge, aryballos—a mixture less common than athletic paraphernalia alone, as on anonymous tumuli on Boston 13.169 (Abbreviation: ARV1Beazley, J. D. 1942. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 188.59; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 3029) and Oxford 1966.854 (Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 3028). Jiang (“Kleophrades Painter,” 214–15) is surely correct in identifying some feathery lines of dilute gloss on the lower right portion of the Emory fragment that joins Fragment 1 as a commemorative lock of hair, for a similar lock appears on the tumulus by Makron. The tomb on Makron’s cup is pushed under a handle, while the Kleophrades Painter instead placed it front and center on his krater, flanked by draped figures who are more likely to be mourning than sacrificing. There is no indication of voting, but it is worth noting that the quarreling warriors on the artist’s calyx-krater in Paris, Louvre G 48 (supra), who were surely disputing the armor of Achilles, are also placed opposite a scene of arming. Jiang seeks in epic poetry the inspiration for the welter of scenes in this period related to the armor of Achilles, while Clairmont, speaking of the former Vermeule fragments, noted that they are essentially the same date as the burial tumulus at Marathon: C. W. Clairmont, Patrios Nomos: Public Burial in Athens during the Fifth and Fourth Centuries B.C. (Oxford, 1983), 84, 283, n. 56.