Provenance

1997, gift, Emily T. Vermeule and Cornelius C. Vermeule III (Cambridge, MA) to Princeton University.

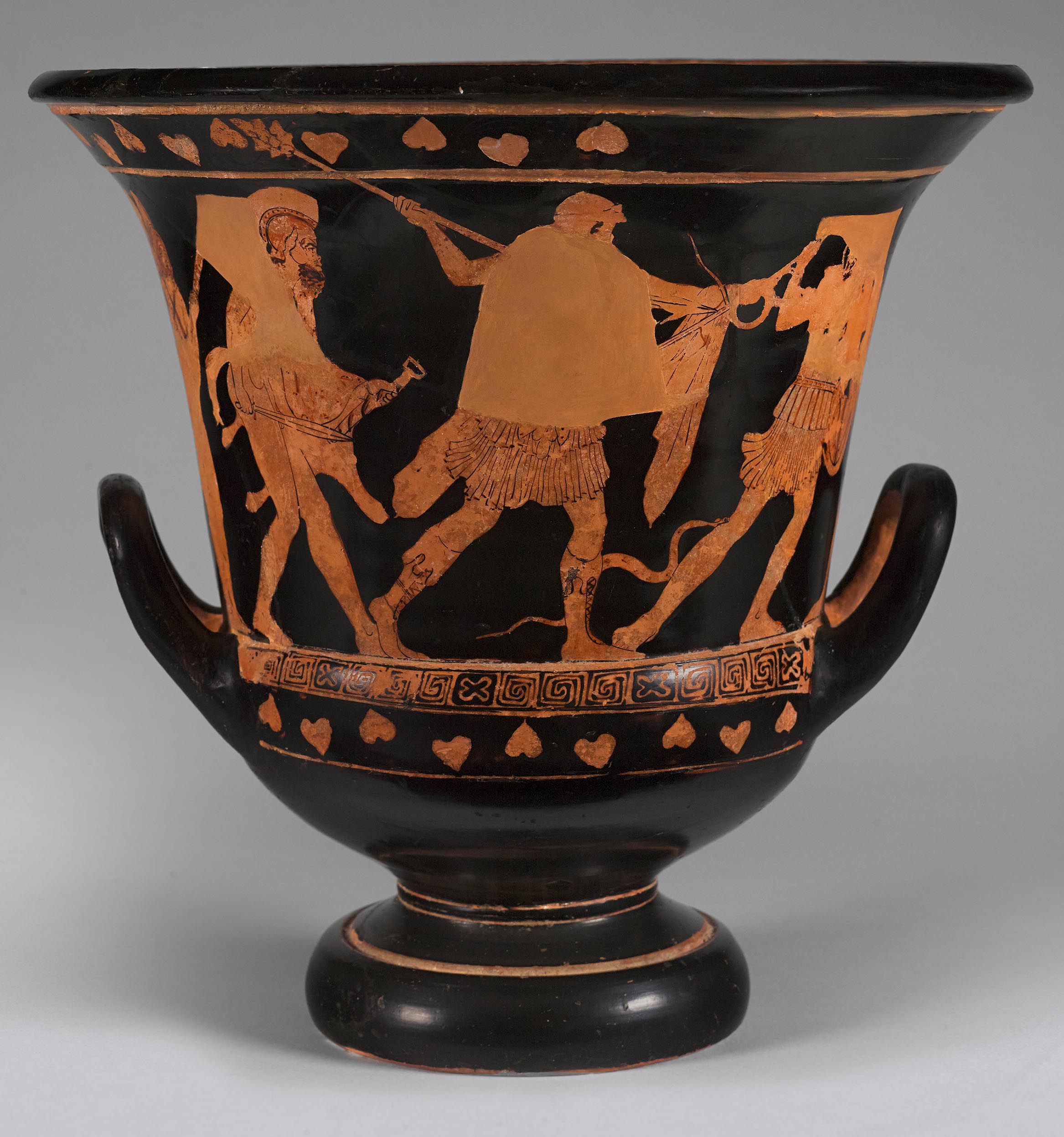

Shape and Ornament

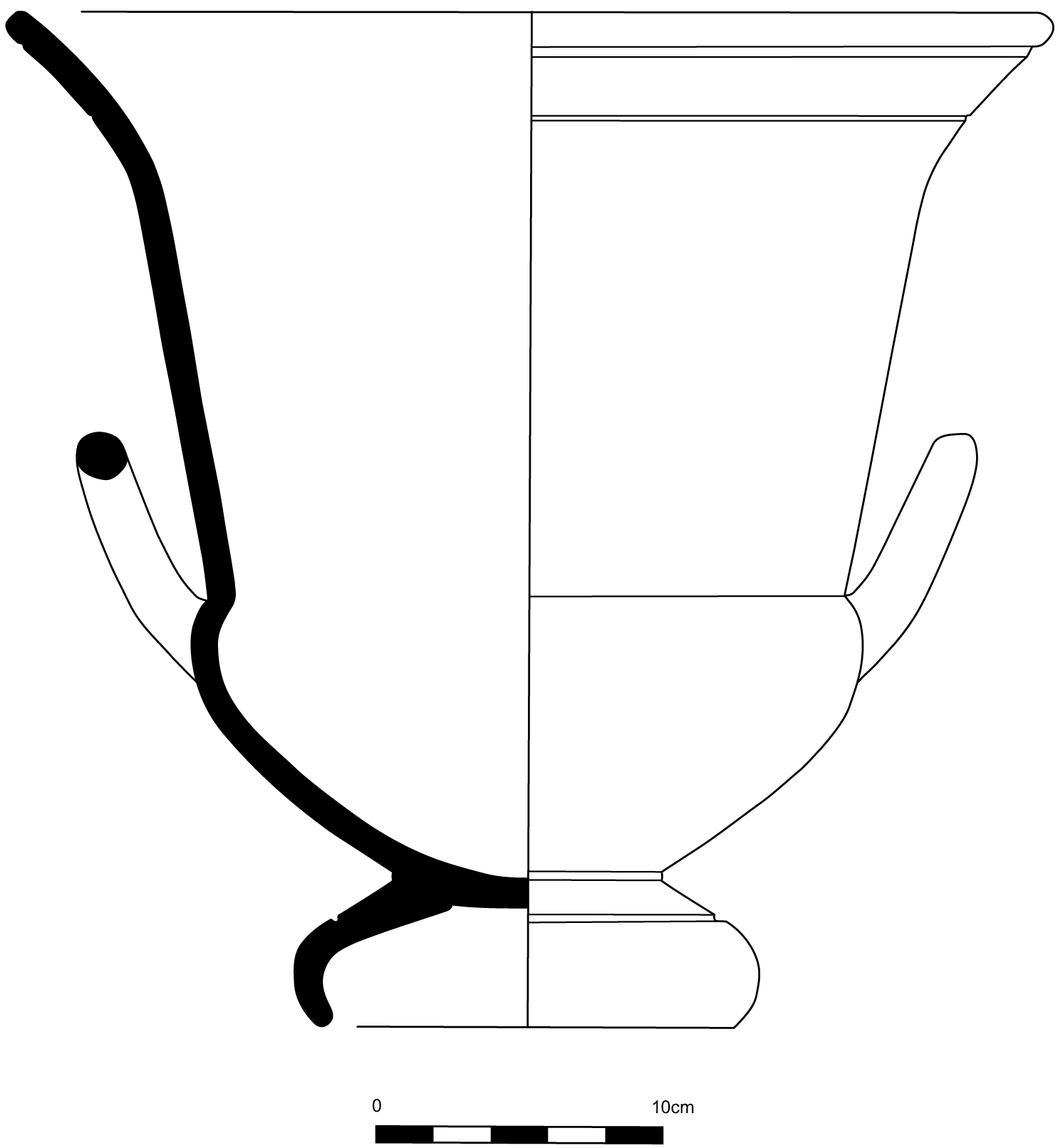

Flaring rim with rounded lip above a wide fascia (h. 2.3 cm), framed by reserved grooves. Circling the fascia, an ivy vine band with reserved leaves and white vines and berries, the added color now worn. Interior black except for a reserved band just below the rim and another 4.5 cm farther down. Upturned handles, round in section, rising from the offset cul; interior of handles reserved. Vines, identical to those on the rim, extend between the handles on the cul. Above the vines but still on the cul, ornamental bands serving as groundlines: groups of three stopt meanders alternating with blackened saltire squares. Black fillet framed by two grooves at join of body and foot. Torus foot in two degrees, with a reserved groove near the top; the reserved underside is hollow, with a narrow resting surface.

Subject

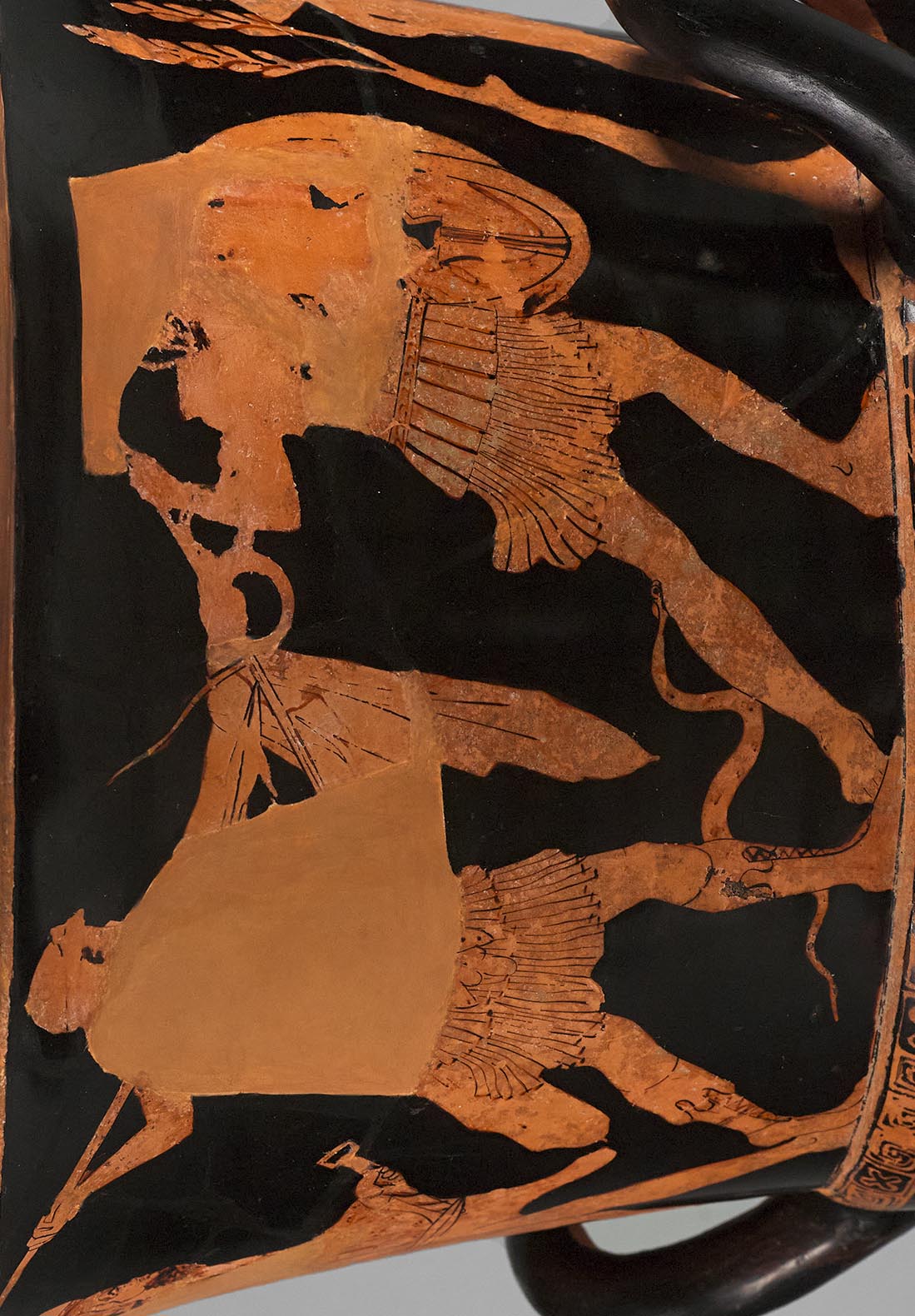

A. Gigantomachy. Dionysos attacks a giant, the former striding to the right with a thyrsos-spear in his raised right hand, its ivy end crossing into the vine pattern above. The snake in his extended left hand bites the giant on the arm, while a second serpent snaps at the giant’s legs. Dionysos wears soft embades (leather boots), a short belted chiton, a nebris (deer skin), and an alopekis (animal-skin cap). The cloak over his left arm extends in front of his body, over his right shoulder, and trails behind his right leg. The giant reels to the right, with his right leg foreshortened and frontal as it drags behind him. He bleeds from his right arm. He wears a short chiton and cuirass and holds a round shield on his left arm—foreshortened to show the interior—and a spear in his right hand, which he directs back toward Dionysos. His face is lost but may have been depicted in three-quarter view. At the far left, behind Dionysos, a satyr moves in profile to the right, approaching the fight timidly, as suggested by his hunched posture. He holds a sword in his right hand and a scabbard in his left. He is naked except for an animal skin draped over his left arm and shoulder and a crested Chalcidian helmet.

B. Gigantomachy. Satyrs drive two bigas toward Dionysos, continuing the scene on side A. Each biga is driven by a satyr and pulled by two satyrs. The wheels seem to have eight spokes, but one of the spokes on the biga at the right is interrupted by the platform of the car, suggesting that the spoke lies behind the platform, and that the painter actually has depicted two four-spoke wheels. The driver of this chariot, which approaches the satyr on side A, is lost except for an extended arm holding a salpinx (war trumpet). Two satyrs are yoked to the chariot with crossed breast straps, one beardless and the other bearded, and positioned above handle BA. The bearded satyr’s face is in three-quarter view, while the beardless satyr is depicted in profile to the right. Both wear crested Chalcidian helmets. The beardless satyr grips his chest straps, while the bearded satyr carries a thyrsos. The driver of the second chariot, at the left, is nude except for an animal skin and an alopekis. He holds the reins with both hands while also holding a thyrsos in his right hand. The two satyrs pulling this chariot are lost except for their lower legs, the tip of a tail, and a helmet crest. Farther left, above handle AB, stands a bearded satyr, his head in profile to the right and his torso frontal, and a small satyr-boy in profile to the left. The older satyr tilts his head back and raises his left hand before his head. The satyr-boy grips a long shaft in his hands, most likely a torch. They are both nude. To the left of the bearded satyr, and marking the division between sides A and B, stands a short tree.

Attribution and Date

Attributed to the Phiale Painter [J. H. Oakley/J. M. Padgett]. Circa 440–430 BCE.

Dimensions and Condition

h. 35.4 cm; w. at handles 31.4 cm; diam. of mouth 36.6 cm; diam. of foot 16.3 cm. Broken and mended, with missing pieces restored in plaster. Repainting largely limited to cracks. Handle AB is restored and painted to match the preserved handle BA. Significant missing figural elements include: on side A, torso and lower face of Dionysos, the head of the giant, and large portions of the rim; on side B, the bodies and heads of the two satyrs pulling the chariot at the left, and almost all of the satyr driving the chariot at the right. The reserved red clay is eroded throughout, especially on side B, where details on the bodies and chariots are highly worn. On the rim are three drill holes from an ancient repair.

Technical Features

Preliminary sketch. Relief contours used sparingly. Accessory color. Red: giant’s blood, baldric of satyr on side A. White: ivy vines and berries. Dilute gloss: breast straps, helmets, beards, and tails of the satyrs; leaves of the tree; the giant’s belt; Dionysos’s boots; the textured skin of the snakes.

Bibliography

D. M. Buitron, Attic Vase Painting in New England Collections, exh. cat., Fogg Art Museum (Cambridge, MA, 1972), 132–33, no. 73; C. C. Vermeule, “Greek Vases for Boston: Attic Geometric to Sicilian Hellenistic,” Abbreviation: BurlMagThe Burlington Magazine 115, no. 839 (1973): 117, figs. 66–68; M. Braverman, The Classical Shape: Decorated Pottery of the Ancient World, exh. cat., St. Paul’s School (Concord, NH, 1984), no. 30.

Comparanda

For the Phiale Painter, see Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1014–26, 1678; Abbreviation: ParalipomenaJ. D. Beazley. Paralipomena: Additions to Attic Black-Figure Vase-Painters and to Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. Oxford, 1971 440–41, 516; Abbreviation: BAdd2Carpenter, T. H., ed. 1989. Beazley Addenda: Additional References to ABV, ARV2, and Paralipomena. 2nd ed. Oxford: Published for the British Academy by Oxford University Press. 315; C. Isler-Kerényi, “Chronologie und Synchronologie attischer Vasenmaler der Parthenonzeit,” Abbreviation: AntK-BHAntike Kunst: Beiheft 9 (1973): 24–25; J. H. Oakley, The Phiale Painter (Mainz, 1990); Abbreviation: Robertson, Art of Vase-PaintingM. Robertson, The Art of Vase-Painting in Classical Athens. Cambridge, 1992, 206–9, 216–17; Oakley, “Attische rotfigurige Pelike des Phiale-Malers und weitere Addenda,” Abbreviation: AAArchäologischer Anzeiger (1995): 495–501; id., Achilles Painter, 100; R. F. Cook, “Red-Figured Lekythoi by the Phiale Painter,” in Essays in Honor of Dietrich von Bothmer, eds. A. J. Clark and J. S. Gaunt (Amsterdam, 2002), 99–105; Oakley, “Neue Vasen des Achilleus-Malers und des Phiale-Malers,” in Meisterwerke: Internationales Symposion anlässlich des 150. Geburtstages von Adolf Furtwängler; Freiburg im Breisgau, 30. Juni–3. Juli 2003, ed. V. M. Strocka (Berlin, 2005), 285–98. The Phiale Painter depicted a wide range of Dionysiac scenes (see Oakley, Phiale Painter, 36), but this portrayal of the god’s participation in the Gigantomachy is unique in his oeuvre, as are the satyr bigas. For closer parallels to the Princeton satyrs, in particular the hunched satyr on side A, whose face is the best preserved and highly individualized, cf., inter alia, Compiègne 968 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1015.24; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 214201); Naples, STG 240 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1015.22; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 214199). Note in particular the thick and sharply arched eyebrows and the dilute gloss beards. For the beardless satyr pulling the biga, including, again, the arched eyebrow and the rather angular and protruding chin, cf. the beardless satyr on side A of Paris, Louvre G 422 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1019.77; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 214255). The embades and alopekis are closely paralleled elsewhere in the work of the Phiale Painter, although not in association with Dionysos. For the embades, cf. Vatican 16549 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1020.92, 1579; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 214272); Naples M 1342 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1020.93; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 214273). For the alopekis, cf. two Thracians wearing alopekides on Altenburg 281 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1015.25; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 214202).

For the ivy vine on the rim, cf. two other calyx-kraters by the Phiale Painter: said to be from Chiusi by Beazley, now lost (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1018.67; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 214245); once New York art market [attributed by J. M. Padgett] (Sotheby’s, Antiquities, auc. cat., December 12, 2014, New York, NY, lot 17; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 9035948). They also appear on a calyx-krater by the Achilles Painter: once London art market (Christie’s, Antiquities, auc. cat., July 3, 1996, London, lot 72; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 20395). An unattributed rim fragment from Marzabotto is likely from the same workshop: Marzabotto 137 (V. Baldoni, La ceramica attica dagli scavi ottocenteschi di Marzabotto [Bologna, 2009], 113, no. 138, pl. 10.138; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 9028952). The Phiale Painter decorated at least seventeen calyx-kraters: see Oakley, Phiale Painter, 49–50. Only five are preserved sufficiently for dimensions, which are close to those of Princeton’s krater, including the nearly equal height and diameter, a phenomenon that first occurs in the second half of the fifth century: see M. B. Moore, Attic Red-Figured and White-Ground Pottery, Abbreviation: AgoraAthenian Agora (Princeton 1953– ) 30 (Princeton, NJ, 1997), 27. Although Oakley (Phiale Painter, 50) at first suggested that all of the Phiale Painter’s calyx-kraters may have been made by a single potter, he later (Achilles Painter, 83) divided them between the S Potter and a second potter, possibly the BP (Big Pot) Potter, who collaborated with many of the painters in the workshop of the Achilles and Phiale Painters. The S Potter’s name derives from the characteristic S-curve of the underside of the feet of his pots. A distinctive feature of his calyx-kraters is a slanted offset beneath the ornamental band on the fascia: cf., by the Phiale Painter, London E 464 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1018.60; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 214238); by the Achilles Painter, Ferrara 2890 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 991.53, 1568, 1677; Abbreviation: Oakley, Achilles PainterOakley, J. H. 1997. The Achilles Painter. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern., fig. 21; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 213874). The underside of the foot in Princeton, however, between the center and the outer curve, is only slightly arced, and the offset beneath the rim fascia is recessed into the wall to form a groove, rather than being sharply angled. These characteristics, in addition to the fillet framed by incised lines at the juncture of the foot and body, and the notch marking the outer edge of the foot, suggest that Princeton’s krater belongs to Oakley’s second potter, possibly the BP Potter: cf. Orvieto 2632 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1018.64; Oakley, Phiale Painter, fig. 6b; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 214242); Ferrara 2798 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1017.55; Oakley, Phiale Painter, fig. 6a; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 214233). For a more general discussion of the shape during the period of the Achilles and Phiale Painters, see S. Frank, Attische Kelchkratere: Eine Untersuchung zum Zusammenspiel von Gefässform und Bemalung (Frankfurt, 1990), 207–32.

For Dionysos’s participation in the Gigantomachy, with the help of his satyrs, see A. Veneri, in Abbreviation: LIMCLexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae. 1981–2009 3 (1986), 474–78, pls. 369–75, nos. 609–59, s.v. “Dionysos”; Abbreviation: Carpenter, Dionysian ImageryT. H. Carpenter. Dionysian Imagery in Fifth-Century Athens. Oxford, 1997, 15–34. Satyr bigas outside the clear context of a Gigantomachy begin to appear on a few late black-figure vases (e.g., Munich J 1119: CVA Munich 1 [Germany 3], pls. 24.3, 27.1; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 12378), but reach their peak popularity on red-figure vases of the first half of the fifth century, as do related depictions of satyrs in armor. This vase is one of the latest in the series. For a sense of the range of the satyr biga theme in vase-painting, cf. Brussels 11 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 513; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 205763); Orvieto 1044 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 657.1; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 207660); Athens, Marathon St. inv. 0.70 (Abbreviation: Carpenter, Dionysian ImageryT. H. Carpenter. Dionysian Imagery in Fifth-Century Athens. Oxford, 1997, pl. 4b); Athens, M. Vlasto (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 291.24; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 202998); Boston 00.342 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 598.4, 1661; Abbreviation: BAdd2Carpenter, T. H., ed. 1989. Beazley Addenda: Additional References to ABV, ARV2, and Paralipomena. 2nd ed. Oxford: Published for the British Academy by Oxford University Press. 265; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 206926).

The depiction of satyrs assisting Dionysos with a biga could have humorous intent, parodying the standard Gigantomachy, which commonly features gods driving chariots. The parodic content of such scenes is clear on a cup by Onesimos in Athens (Abbreviation: Carpenter, Dionysian ImageryT. H. Carpenter. Dionysian Imagery in Fifth-Century Athens. Oxford, 1997, 25–28, pl. 4a–b), which juxtaposes a chariot driven by Zeus on the interior with a chariot driven by satyrs on the exterior. For the use of satyrs to parody traditional mythological narratives, see A. G. Mitchell, Greek Vase-Painting and the Origins of Visual Humor (Cambridge, UK, 2009), 219–34. For a critique of the parodic interpretation of satyrs assisting Dionysos in the Gigantomachy, see Isler-Kerényi, “Review of Dionysian Imagery, by T. Carpenter,” Abbreviation: GnomonGnomon: Kritische Zeitschrift für die gesamte klassische Altertumswissenschaft 72 (2000): 430–37.

Brommer argued that the satyr biga and the theme of armed satyrs was first introduced in a satyr play: F. Brommer, Satyrspiele (Berlin, 1959), 17. See also, for the connection between vase-paintings and satyr plays in general, E. Simon, “Satyr-Plays on Vases in the Time of Aeschylus,” in The Eye of Greece: Studies in the Art of Athens, eds. D. C. Kurtz and B. A. Sparkes (Cambridge, UK, 1982), 123–48. Satyrs appear in a wide variety of scenes in the Phiale Painter’s oeuvre, and Brommer (Satyrspiele, 58–65) also suggested that lost satyr plays were the stimulus for at least two others: Paris, Louvre G 422 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1019.77; Oakley, Phiale Painter, no. 77, pl. 59, fig. 9a; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 214255) and Naples STG 240 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1015.22; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 214199). Although it is likely that the satyr biga was meant to be parodic to some extent, this does not necessarily mean that a satyr play inspired the theme. No evidence outside of the vases points to the existence of plays involving satyrs driving bigas. Nor is there any external evidence for plays having inspired the other satyr scenes painted by the Phiale Painter. Indeed, vase-painters could easily have invented their own satyr parodies without relying on the theater. Furthermore, the satyrs do not wear the distinctive perizommeta (shorts) that would have made explicit their identification as actors, as for instance those worn by the satyrs driving and pulling a biga on a chous from Thorikos: Thorikos excavations TC75.274 (E. Goosens, “A Red-Figured Chous with Satyrs from Thorikos,” in Studies in South Attica 2, ed. H. Mussche [Ghent, 1994], 115–19; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 390546). For critiques of the satyr-play thesis, see F. Lissarrague, “Why Satyrs are Good to Represent,” in Nothing to do with Dionysos? Athenian Drama in Its Social Context, eds. J. J. Winkler and F. I. Zeitlin (Princeton, NJ, 1990), 228–36; Abbreviation: Carpenter, Dionysian ImageryT. H. Carpenter. Dionysian Imagery in Fifth-Century Athens. Oxford, 1997, 27–28. For recent overviews of the connection between vase-painting and satyr plays, see R. Krumeich, “Images of Satyrs and the Reception of Satyr Drama-Performances in Athenian and South Italian Vase-Painting,” in Reconstructing Satyr Drama, eds. A. Antonopoulos, M. Christopoulos, and G. W. M. Harrison (Berlin, 2021), 587–636; T. J. Smith, “Heads or Tails? Satyrs, Komasts, and Dance in Black-Figure Vase-Painting,” in ibid., 637–68; H. N. Pritchett, “When does a Satyr become a Satyr? Examining Satyr Children in Athenian Vase-Painting,” in ibid., 717–34.

Dionysos’s Thracian garb becomes an occasional attribute of the god during the course of the fifth century: Abbreviation: Carpenter, Dionysian ImageryT. H. Carpenter. Dionysian Imagery in Fifth-Century Athens. Oxford, 1997, 19–20. The purpose may have been to signal the god’s Thracian connections, most famously his confrontation with the Thracian king Lykurgos. When Dionysos wears boots, he almost always wears the Thracian type, embades, with soft flaps at the top, which are first associated with him in depictions of the Gigantomachy: cf. a cup by Oltos, London E 8 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 63.88; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 200524); an Early Classical stamnos by the Blenheim Painter, Boston 00.342 (supra). No other example of Dionysos wearing an alopekis has been found, but this headgear further strengthens the god’s connection with Thrace.