Provenance

1986, sale, Münzen und Medaillen AG (Basel) to Princeton University [y1986-59 a–e]; 1990, gift, J. Robert Guy to Princeton University [y1990-26].

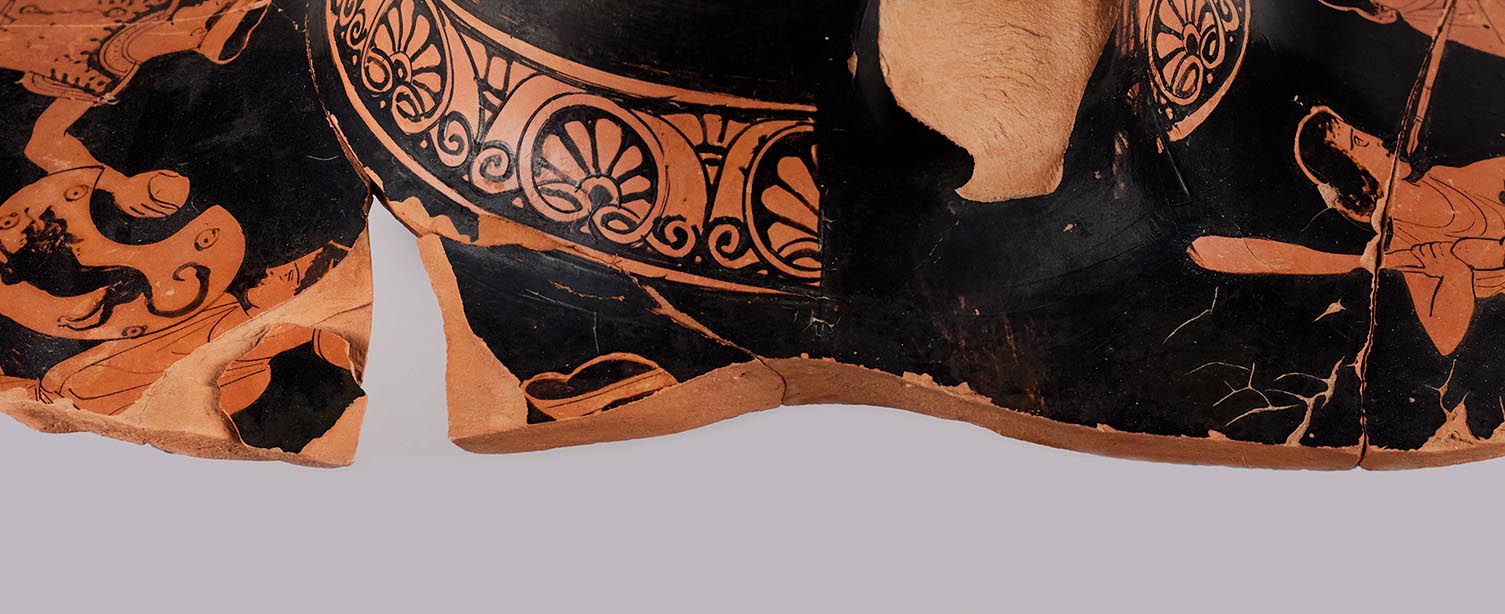

Shape and Ornament

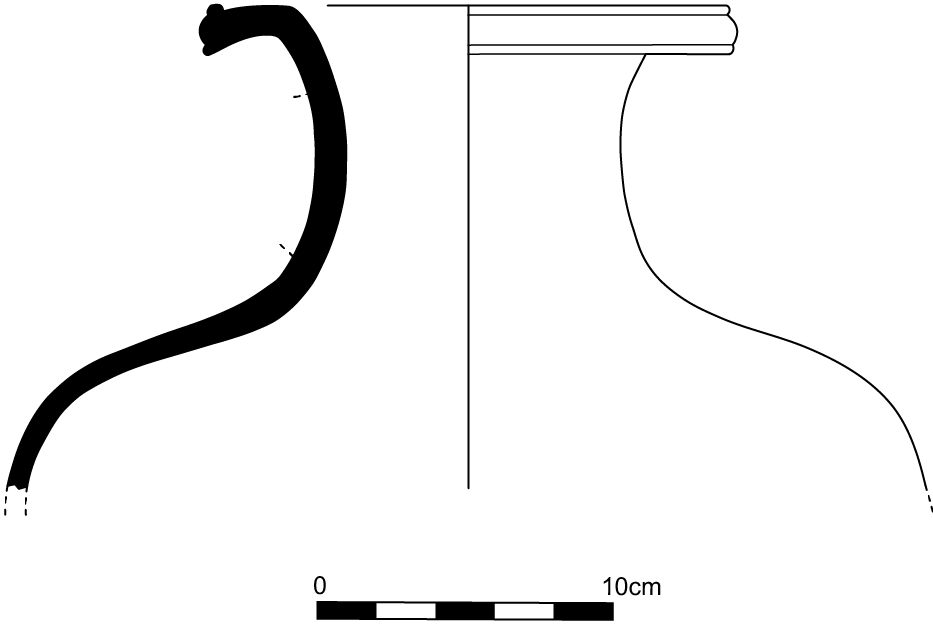

Joined fragments from mouth, neck, and shoulder of a kalpis-hydria and five nonjoining body fragments. Rim molded in two degrees; slender, rounded black lip above painted ovolo molding, the latter framed by reserved grooves. Sloping top of rim reserved. Interior of mouth and neck black. At base of neck, band of upright palmettes, alternating with and enclosed by plump lotuses. Continuous curve between neck and shoulder. Band of ovolo framed by two reserved stripes below figures on shoulder (only small section preserved to the left of central group). Interior of body fragments reserved.

Subject

Death of Orpheus. Seven Thracian women bearing weapons attack Orpheus. Aside from the woman immediately to the right of Orpheus, who wears a belted ependytes (tunic) over her peplos, all the other women wear peploi with thin, pointed battlement patterns along the lower hems and overfalls. The woman at the far left of the scene brandishes a large wooden pestle in both hands as she rushes to the right toward Orpheus, her face in profile and her torso twisted back in a three-quarter view. Before her, another assailant runs to the right with widespread legs, profile head, and three-quarter torso; she carries a spear in her right hand, angled diagonally toward the ground, and extends her left arm for balance before striking. A cloak with a battlement pattern above its hem is draped over her left arm. Both of these women have noticeably short hair. To the immediate left of Orpheus two other women stab him with spears. The first woman wears a sakkos, and her peplos has an additional battlement pattern at the level of her breasts, possibly on a separate garment. She holds the lowered spear by her waist. The woman closest to Orpheus has her hair pulled back in a chignon that is held in place by a wide, reserved bandeau, from which emerge leaves in added color. She wears earrings and a necklace. The interior of the pelta shield on her left arm bears an emblem of a hound or lion. She raises her spear high for a killing stab, but grasps it with only two fingers, in the manner of an akontist fingering the thongs on a javelin. Both women move to the right with their heads in profile and their torsos twisted in three-quarter view as they thrust the spears toward Orpheus.

Orpheus, already falling to the ground, raises his lyre high above his head in his right hand, perhaps in self-defense. He may have extended his left arm behind him to brace for the fall, but the arm is not preserved. One of the arms of his lyre is broken, and the missing body of the instrument seems to have been separated from the arms. Relief lines are visible demarcating the contours of the tortoise shell, but the painter either decided not to depict it, or it lay on the ground near the singer’s missing lower body. Orpheus appears to be nude, aside from a cloak draped over his right shoulder. He wears a distinctive Thracian headpiece made of animal skin, an alopekis, with the face of the animal visible in detail.

Three additional women moving to the left assail Orpheus from the right. The first wears a patterned ependytes (tunic) and has her hair bound in the same manner as the woman spearing Orpheus. She winds up to strike Orpheus with a stone held in her raised right hand, her back turned toward the viewer and her face in profile. She extends her left arm and holds in her left hand the folds of a short cloak draped over her shoulder. To her right, a sixth woman in profile to the left approaches with a spear in her right hand, lowered to her waist, and a pelta with a hound device on her left arm. Her head is damaged, but she may wear the same kind of wide bandeau as the woman with the stone. Lastly, at far right, the top of the head of a seventh woman is preserved, also with a bandeau. Although she faces to the right, toward the position of the vertical handle, we must imagine her also charging toward Orpheus, but turning to look behind her.

Attribution and Date

Attributed to Polygnotos [J. R. Guy]. Circa 440–430 BCE.

Dimensions and Condition

Fragment a: h. 16.4 cm; diam. 31.1 cm; diam. of mouth 18.0 cm.

Fragment b (several joined fragments): 25.7 × 17.8 cm; thickness 1.1 cm.

Fragment c (two joined fragments): 18.2 × 10.1 cm; thickness 1.1 cm.

Fragment d: 16.8 × 9.6 cm; thickness 1.2 cm.

Fragment e (two joined fragments): 14.1 × 8.6 cm; thickness 1.4 cm.

y1990-26: 10.4 × 4.4 cm; thickness 0.7 cm.

Several joining fragments form the principal fragment (Fragment a), preserving most of the rim and neck, and large portions of the shoulder. Much of the lower portion of the shoulder in front is missing, including the bottom halves of Orpheus and the two assailants to his left. No figure is preserved entirely. The back of the kalpis neck is mostly lost, including the handle and all but the hair of one of the Thracian women. One small gap in the top of the rim filled with plaster, as well as other smaller gaps and cracks below.

Four nonjoining body fragments (Fragments b–e) and a fifth separately numbered fragment (y1990-26), given their relatively sharp curvature and thickness, most likely come from the lower body of the kalpis. All broken on all sides. Handles and foot missing entirely.

Technical Features

Preliminary sketch. Relief contours. Accessory color. White: leaves on the garland of the figure to Orpheus’s immediate left. Red: pegs of Orpheus’s lyre; inscription. Matheson (Abbreviation: Matheson, PolygnotosS. B. Matheson. Polygnotos and Vase Painting in Classical Athens. Madison, Wisc., 1995, 330 n. 78) notes “rays in added red like a nimbus around his head” although no trace survives, if they ever existed. Dilute gloss: details on Orpheus’s alopekis; the arm straps for the peltai; the pattern on the tunic of the woman to Orpheus’s immediate right.

Inscriptions

[OP]OEUS directly to the right of Orpheus.

Bibliography

F. Lissarrague, “Orphée mis à mort,” Musica e Storia 2 (1994): 282–83, 302–3, figs. 11a–b; M.- X. Garezou, in Abbreviation: LIMCLexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae. 1981–2009 7 (1994), 87, pl. 64, no. 57, s.v. “Orpheus”; Abbreviation: Matheson, PolygnotosS. B. Matheson. Polygnotos and Vase Painting in Classical Athens. Madison, Wisc., 1995, 360, no. P 66, pl. 59a–b; D. Tsiafakis, Η Θράκη στην Αττική εικονογραφία του 5ου αι. π.Χ.: Προσεγγίσεις σας σχέσεις Αθήνας και Θράκης (Komotini, 1998), 335, fig. 13a; Abbreviation: AVIImmerwahr, H. R., and R. Wachter. Attic Vase Inscriptions. https://avi.unibas.ch (last update October 25, 2018). 6852; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 19146.

Comparanda

For Polygnotos, see Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1027–35, 1678–79; Abbreviation: ParalipomenaJ. D. Beazley. Paralipomena: Additions to Attic Black-Figure Vase-Painters and to Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. Oxford, 1971 442; Abbreviation: BAdd2Carpenter, T. H., ed. 1989. Beazley Addenda: Additional References to ABV, ARV2, and Paralipomena. 2nd ed. Oxford: Published for the British Academy by Oxford University Press. 317; C. Isler-Kerényi, “Chronologie und synchronologie attischer vasenmaler der Parthenonzeit,” Abbreviation: AntK-BHAntike Kunst: Beiheft 9 (1973): 23–32; M. Halm-Tisserant, “Tradition et renouveau: Deux types iconographiques—Dionysus, Hephaestus—au sein de l’atelier de Polygnotos,” in Abbreviation: Ancient Greek and Related PotteryAncient Greek and Related Pottery: Proceedings of the International Vase Symposium in Amsterdam, 12–15 April 1984. Edited by H. A. G. Brijder. Amsterdam, 1984, 185–89; S. B. Matheson, “Polygnotos: An Iliupersis Scene at the Getty Museum,” in Abbreviation: GkVasesGetty 3Frel, J., and M. True, eds. 1986. Greek Vases in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Vol. 3. Occasional Papers on Antiquities 2. Malibu: J. Paul Getty Museum., 101–14; Abbreviation: Robertson, Art of Vase-PaintingM. Robertson, The Art of Vase-Painting in Classical Athens. Cambridge, 1992, 210–11; id., “The Chronology of the Vase Painter Polygnotos and Some New Attributions,” Abbreviation: AJAAmerican Journal of Archaeology 96 (1994): 305; Abbreviation: Matheson, PolygnotosS. B. Matheson. Polygnotos and Vase Painting in Classical Athens. Madison, Wisc., 1995, esp. 7–80. Polygnotos signed five extant vases: an amphora, a pelike, two stamnoi, and a fragmentary krater. Beazley referred to the artist as Polygnotos I in order to distinguish him from two other vase-painters, the Lewis Painter and the Nausicaa Painter—respectively Polygnotos II and III—who signed some of their works with the same name. It is generally assumed that these three vase-painters adopted this name in homage to the great wall-painter, Polygnotos of Thasos. Polygnotos I, however, seems to share less in common with the monumental compositions of the famous muralist than his immediate predecessors in the workshop of the Niobid Painter: see E. Simon, “Polygnotan Painting and the Niobid Painter,” Abbreviation: AJAAmerican Journal of Archaeology (1963): 43–62; Abbreviation: Prange, NiobidenmalerPrange, M. 1989. Der Niobidenmaler und seine Werkstatt: Untersuchungen zu einer Vasenwerkstatt frühklassischer Zeit. Frankfurt: Peter Lang., 87–110. This led Robertson (Abbreviation: Robertson, Art of Vase-PaintingM. Robertson, The Art of Vase-Painting in Classical Athens. Cambridge, 1992, 210) to suggest that one of the Niobidean painters may have named his son Polygnotos (Beazley’s Polygnotos I) as an homage to the earlier muralist. For the connection between the Niobid Painter and Polygnotos, especially in his early works, see Abbreviation: Prange, NiobidenmalerPrange, M. 1989. Der Niobidenmaler und seine Werkstatt: Untersuchungen zu einer Vasenwerkstatt frühklassischer Zeit. Frankfurt: Peter Lang., 117–18; Abbreviation: Matheson, PolygnotosS. B. Matheson. Polygnotos and Vase Painting in Classical Athens. Madison, Wisc., 1995, 9–27; Abbreviation: Williams, “Workshop View”Williams, D. 2017. “Beyond the Berlin Painter: Toward a Workshop View.” In Padgett, Berlin Painter, 144–88. 158–60.

For the development of figural compositions on the shoulders of Polygnotan hydriai, see Abbreviation: Matheson, PolygnotosS. B. Matheson. Polygnotos and Vase Painting in Classical Athens. Madison, Wisc., 1995, 74–80. Matheson places Princeton’s vase in an intermediate to late stage of Polygnotos’s stylistic development, one marked, in particular, by a simplification of forms such as drapery. Note, for example, the straight hems of the women’s peploi, into which the fold lines of the garment disappear, and compare with these the more carefully executed drapery of the figures on a hydria in Ferrara, also attributed to Polygnotos: Ferrara 3058 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1032.58, 1679; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 213441). Individual details of anatomy, especially facial details, remain largely the same on his shoulder figures. Cf., for instance, the long face, squared tips of noses, and downturned mouth of Orpheus on Princeton’s hydria with that of Peleus on the hydria Ferrara 3058 (supra). As on Princeton’s hydria, Polygnotos often filled the entirety of the shoulder zone, right up to the vertical handle: cf. the hydria Ferrara 3058 (supra); Naples 81398 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1032.61; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 213444).

For the shape within the workshop of Polygnotos and his followers, see Abbreviation: Matheson, PolygnotosS. B. Matheson. Polygnotos and Vase Painting in Classical Athens. Madison, Wisc., 1995, 184. Of the ten hydriai attributed to Polygnotos himself, four have pictures on the body, five have them on the shoulder, and one, now lost and unphotographed, had two registers of figures: once Leipzig T 667 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1032.62; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 213445). An eleventh kalpis attributed by Beazley to Polygnotos has been rightly attributed by Matheson to the Peleus Painter: Mississippi, Univ. 1977.3.90 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1032.64; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 213447). Enough remains of the unjoined body fragments from the Princeton vase to say that it did not have two registers, but not to conclude whether there was an additional band of ornament below the ovolo groundline. No other example attributed to Polygnotos has ovolo alone, and at least two combine ovolo with a wider lotus-and-palmette band: Athens 14983 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1032.60; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 213443); Naples 81398 (supra). All of the artist’s five hydriai with figures confined to the shoulder have a lotus-and-palmette band on the neck, and most have painted ovolo on the rim, the exception being Ferrara 3058 (supra), where the ovolo molding is undecorated. Variations on these combinations occur on other hydriai in the larger Group of Polygnotos: cf., by the Coghill Painter, London E 170 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1042.2; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 213536).

For depictions of the death of Orpheus, see L. D. Caskey and J. D. Beazley, Attic Vase Paintings in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (Oxford, 1963), 3:72–76; F. M. Schoeller, Darstellungen des Orpheus in der Antike (Freiburg, 1969); M. Schmidt, “Der Tod des Orpheus in Vasendarstellungen aus schweizer Sammlungen,” in Zur griechischen Kunst, Abbreviation: AntKAntike Kunst Suppl. 9, eds. H. P. Isler and G. Seiterle (Bern, 1973), 95–105; W. Raeck, Zum Barbarenbild in der Kunst Athens im 6. Und 5. Jahrhundert v. Chr. (Bonn, 1981), 67–100; A. Lezzi-Hafter, “Der Tod des Orpheus auf einer Kanne des Shuvalow-Malers,” Abbreviation: AntKAntike Kunst 29 (1986): 90–94; M. Schmidt, “Bemerkungen zu Orpheus in Unterwelts- und Thrakerdarstellung,” in Orphisme et Orphée: En l’honneur de Jean Rudhardt, ed. P. Borgeaud (Geneva, 1991), 31–50; M.-X. Garezou, in Abbreviation: LIMCLexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae. 1981–2009 7 (1994), 84–88, pls. 58–65, nos. 7–67, s.v. “Orpheus”; Lissarrague, “Orphée,” 269–308; Tsiafakis, Η Θράκη, 48–62. Although still popular in the middle of the fifth century, after a peak in popularity in the Early Classical period, the death of Orpheus is represented by only four vases within the Group of Polygnotos, with Princeton’s hydria being the only one by Polygnotos himself. The central group of the falling Orpheus and his immediate assailant is broadly similar compositionally to that on a bell-krater by another Polygnotan artist, the Curti Painter: Harvard 60.343 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1042.2; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 213539). In both cases, the central group follows the so-called Pistoxenos type, which shows Orpheus on his knees defending himself with his lyre held above his head, apparently invented by the Pistoxenos Painter (Schoeller, Darstellungen, 55–59): cf., by the Pistoxenos Painter, Athens 15190 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 860.2; 1580.2; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 211325). Unlike the Curti Painter’s version, Princeton’s hydria shows a strikingly extensive version of the death of Orpheus, with which one may compare another many-figured composition, including the addition of two young males, on a hydria by the Niobid Painter, of whom Polygnotos was a successor: Boston 90.156 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 605.62; Caskey and Beazley, Attic Vase Paintings, 3:72–76, no. 107; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 207002).

In its details, however, the death of Orpheus on the Princeton hydria differs significantly from standard depictions of the subject, Polygnotan and otherwise. The presence of two women bearing peltai is quite rare in the death of Orpheus, and for Thracians in general, with peltai more normally carried by Amazons. According to Lissarrague, only eleven vases, not including Princeton’s kalpis, display Thracians with peltai: F. Lissarrague, L’autre guerrier: Archers, peltastes, cavaliers dans l’imagerie attique (Paris, 1990), 295. Also cf. Oxford 1971.867 (Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 43664). As on the Princeton vase, the peltai presumably function as a marker of foreignness. The hound emblem is rather uncommon, in particular its location on the interior of the shield. Peltai rarely have animal emblems and are more commonly decorated with eyes; for a similar animal device on a pelta, albeit of an earlier date, cf. Villa Giulia 50560 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 11.4, 1618; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 200051). Although not peltai, for the placement of a shield emblem on the interior of the shield, cf. Bologna 290 (Abbreviation: LIMCLexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae. 1981–2009 1 [1981], 178, pl. 138, no. 832, s.v. “Achilles”; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 416); Bologna 289 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 891, 1674; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 211752). The battlement pattern on the Thracian women’s robes is common on the zeira, the quintessential Thracian cloak, but it is rare to see Thracian identity suggested by applying it to Greek clothing types: cf., by the Villa Giulia Painter, Malibu 80.AE.71 (Tsiafaki, Η Θράκη, 344, pl. 22; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 22903).

Although spears, spits, and stones are often used by Thracian women as weapons, the pestle is much more uncommon. Among farm implements, axes and sickles are preferred, but both are absent here. For other instances of Thracians attacking Orpheus with pestles, cf., by the Florence Painter, Ferrara 2795 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 541.7; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 206135); by the Dokimasia Painter, Basel BS 1411 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1652; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 275231). In many versions of Orpheus’s death (e.g., the vase in Malibu [supra]), the Thracian women stab him with obeloi (spits), but that seems not to be the case on the Princeton vase, where the weapons are either spears or javelins; cf., by the Oionokles Painter, London E 301 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 647.12; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 207524), on which a Thracian woman attacks with a spear, although Orpheus has already been transfixed with a obelos. The woman in London has short hair, like the first two women on the Princeton hydria, and this, too, may allude to their ethnicity, as the only Thracian women most Athenians ever saw were enslaved, for whom bobbed hair was an indicator of their low social status: see J. H. Oakley, “Some ‘Other’ Members of the Athenian Household: Maids and Their Mistresses in Fifth-century Athenian Art,” in Abbreviation: Not the Classical IdealNot the Classical Ideal: Athens and the Construction of the Other in Greek Art. Edited by B. Cohen. Leiden, 2000, 246.

In depictions of Orpheus on Athenian vases he usually appears bareheaded, but on Princeton’s kalpis his Thracian lineage is emphasized by the alopekis, which he also wears in several other depictions of his death: e.g., Ferrara 2795 (supra); Würzburg 534 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1123.7; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 214849). Orpheus’s Thracian origins are also occasionally highlighted by embades (Thracian boots): cf., inter alia, calyx-krater fragments attributed to the Blenheim Painter in the Cahn Collection, Basel, HC 361 (Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 22904); the hydria by the Niobid Painter in Boston (supra). Orpheus also occasionally wears garments with patterns typical of Thracian clothing: cf., by the Agrigento Painter, Naples 146739 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 574.6; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 206610). As for the identity of Orpheus’s assailants, there seems to have been two mythological traditions surrounding the death of Orpheus, at the hands of either maenads or Thracians. Vase-painters never explicitly characterize his female assailants as maenads, but frequently make clear that they are Thracians, through additions such as patterned clothing, as on Princeton’s kalpis: see T. H. Carpenter, Art and Myth in Ancient Greece: A Handbook (London, 1991), 82.

Matheson (Abbreviation: Matheson, PolygnotosS. B. Matheson. Polygnotos and Vase Painting in Classical Athens. Madison, Wisc., 1995, 330 n. 78) takes the initial preserved letter in the inscription to be a theta, suggesting the name could be Pentheus, although the subject is clearly the death of Orpheus. In its current state of preservation, the initial letter does not seem to have a crossbar and resembles an omicron more than a theta. The iconographic context, however, justifies reading it as a poorly formed phi. There are several variant forms of phi in Attic vase inscriptions, including the circular phi, occasionally with nothing within the circle: see H. Immerwahr, Attic Script: A Survey (Oxford, 1990), 162–63.