Provenance

1984, Atlantis Antiquities, Ltd. (New York, NY); 1986, gift, Dietrich von Bothmer (Centre Island, NY) to Princeton University.

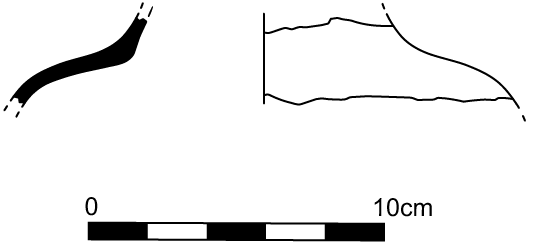

Shape and Ornament

Two joined fragments from the shoulder of a kalpis-hydria. Continuous curve between neck and shoulder; interior of neck black. Elaborate wreath of florals and fruit, most likely olive, extending across the preserved section of neck and upper portion of shoulder. Interior reserved.

Subject

Undetermined. The scene on the body extends onto the shoulder, but little remains. At center left is the top of a male head facing right, and behind him the upper part of a spear, presumably held in his right hand. A vine, most likely grape, with the stems of the leaves incised, occupies the right half of the fragment.

Attribution and Date

Unattributed. Late fifth century BCE.

Dimensions and Condition

h. 2.8 cm; w. 14.0 cm; thickness: at lower edge 0.5 cm; at transition from shoulder to neck 0.7 cm; at neck 0.4 cm. Two joined fragments, broken on all sides. Black gloss slightly mottled and misfired streaky red in places, in particular around the grapevine.

Technical Features

Preliminary sketch. Relief line contours used extensively for the florals but absent on the heads of the man and owl, and the spear. Accessory color. Dilute gloss: husks partially covering the fruit.

Bibliography

Unpublished.

Comparanda

The fragment is significant for the considerable detail in which the floral features are executed. In more stylized versions of florals, it is often hard to distinguish between laurel, myrtle, and olive leaves without a clear context. The extreme care taken in drawing the florals on Princeton’s fragment suggests that the vase-painter had a specific model from nature in mind, and yet it remains difficult to identify the species with certainty. The fruit is large and somewhat pear-shaped, unlike an olive or the fruit of the laurel tree. The fruits emerge from clearly depicted husks, which may indicate that the painter had the round berry of the myrtle in mind, though these are not so large. Myrtle was sacred to Aphrodite, but it also appears on vases where she is not represented in person. For example, on a pyxis with Erotes interacting with men and women, the wreath around the body has been interpreted as myrtle: New York 06.1021.122 (Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 2084). In the case of Princeton’s fragment, however, the lanceolate leaves are more consistent with an identification as an olive wreath: cf. the leaves and olives on the unpublished and unattributed fragment New York 2011.604.2.2407. We should perhaps not expect the vase-painters to have been working directly from nature, but rather from memory, and thus allow for divergences from reality.

Identification of the plant below the olive wreath as a grapevine must remain speculative. Fig leaves tend to be deeply lobed, as often represented on shields; e.g., Harvard 1972.39 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 323.55; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 203306). The leaf shape resembles oak, but the growth habit appears more like a vine than branches, suggesting grape. Grape leaves have serrated edges, a level of detail to which the artist here did not aspire. There are no grapes, but these are often omitted by vase-painters. Alternatively, they may have been represented further down on the body. One may imagine that the man with a spear was facing the god Dionysos, perhaps reclining underneath the grapevine, as on a roughly contemporary chous: New York 06.1021.183 (Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 15851). If this were the case, we are left to wonder at the man’s identity, as companions of Dionysos more normally wield thyrsoi and torches.

For a discussion of Greek wildflowers and their associations in antiquity, see H. Baumann, Greek Wild Flowers and Plant Lore in Ancient Greece, trans. and eds. W. T. Stearn and E. R. Stearn (London, 1993). For floral ornament on Athenian vases, with reference to notions of order, arrangement, and luxury, see N. Kei, L’esthétique des fleurs: Kosmos, poikilia et charis dans la céramique attique du VIe et du Ve siècle av. n. ère (Berlin, 2021). See also id., “The Floral Aesthetics of Attic Red-Figured Pottery: Visual Adornment and Interplay between Ornament and Figure,” in ΦΥΤΑ ΚΑΙ ΖΩΙΑ. Pflanzen und Tiere auf Griechischen Vasen, CVA Österreich 2, eds. C. Lang-Auinger and E. Trinkl (Vienna, 2016), 271–80; E. Kunze-Götte, Myrte als Attribut und Ornament auf attischen Vasen (Kilchberg, 2006).

Earlier kalpides with figures on the body commonly have an ornamental frieze, often ovolo, just above the figural decoration at the base of the neck. Toward the end of the fifth century, and into the fourth, wreaths occasionally occupy this position, although ovolo still remains the most popular ornament. It is rare for such wreaths to be left unframed; cf. the later and much more stylized wreath on the kalpis Vienna 827 (Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 555). For a discussion of kalpides from the end of the fifth century, see A. Lezzi-Hafter, Der Eretria-Maler: Werke und Weggefährten (Mainz, 1988), 172–73, 182.