Provenance

1997, sale, Atlantis Antiquities, Ltd. (New York, NY) to Princeton University.

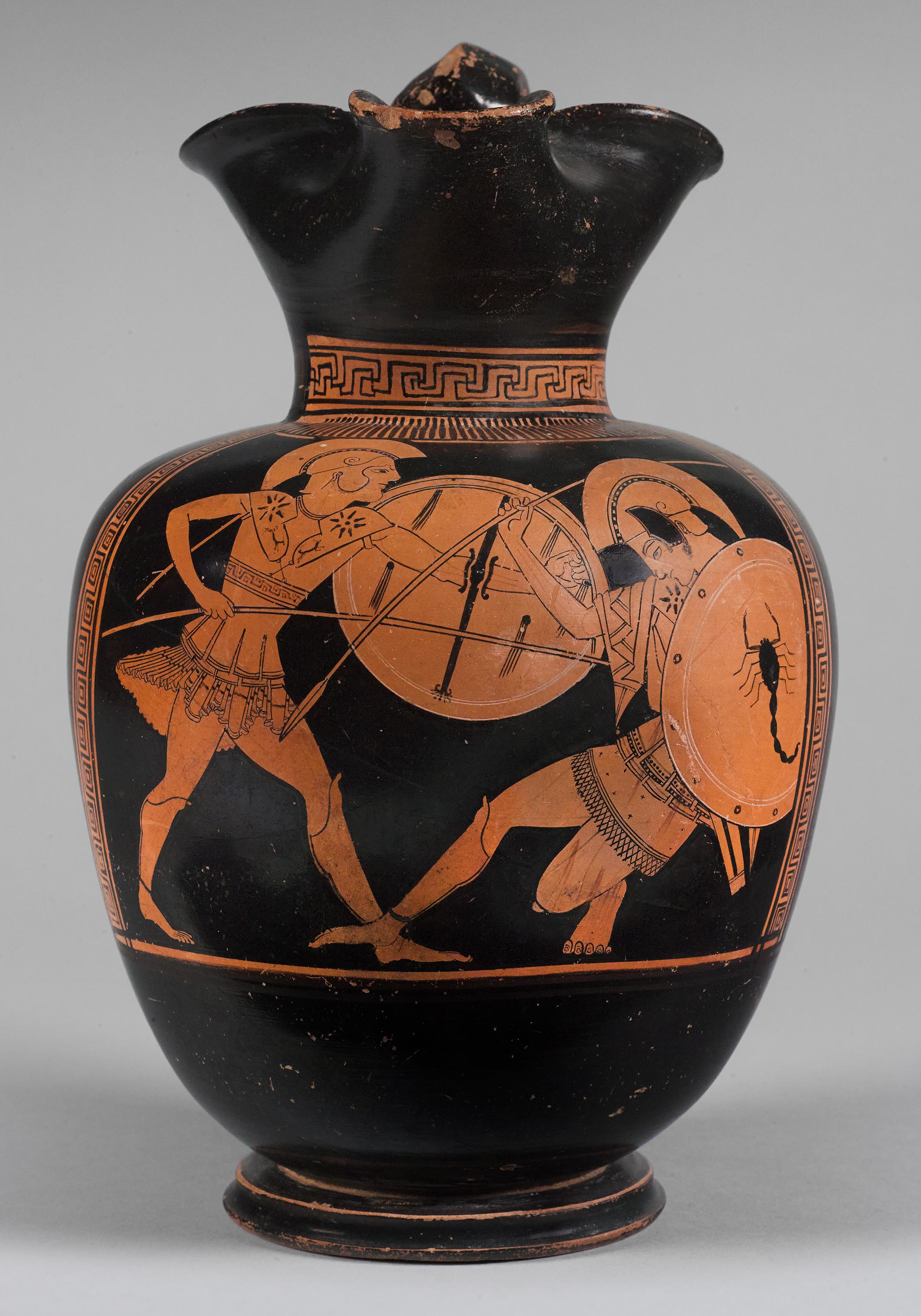

Shape and Ornament

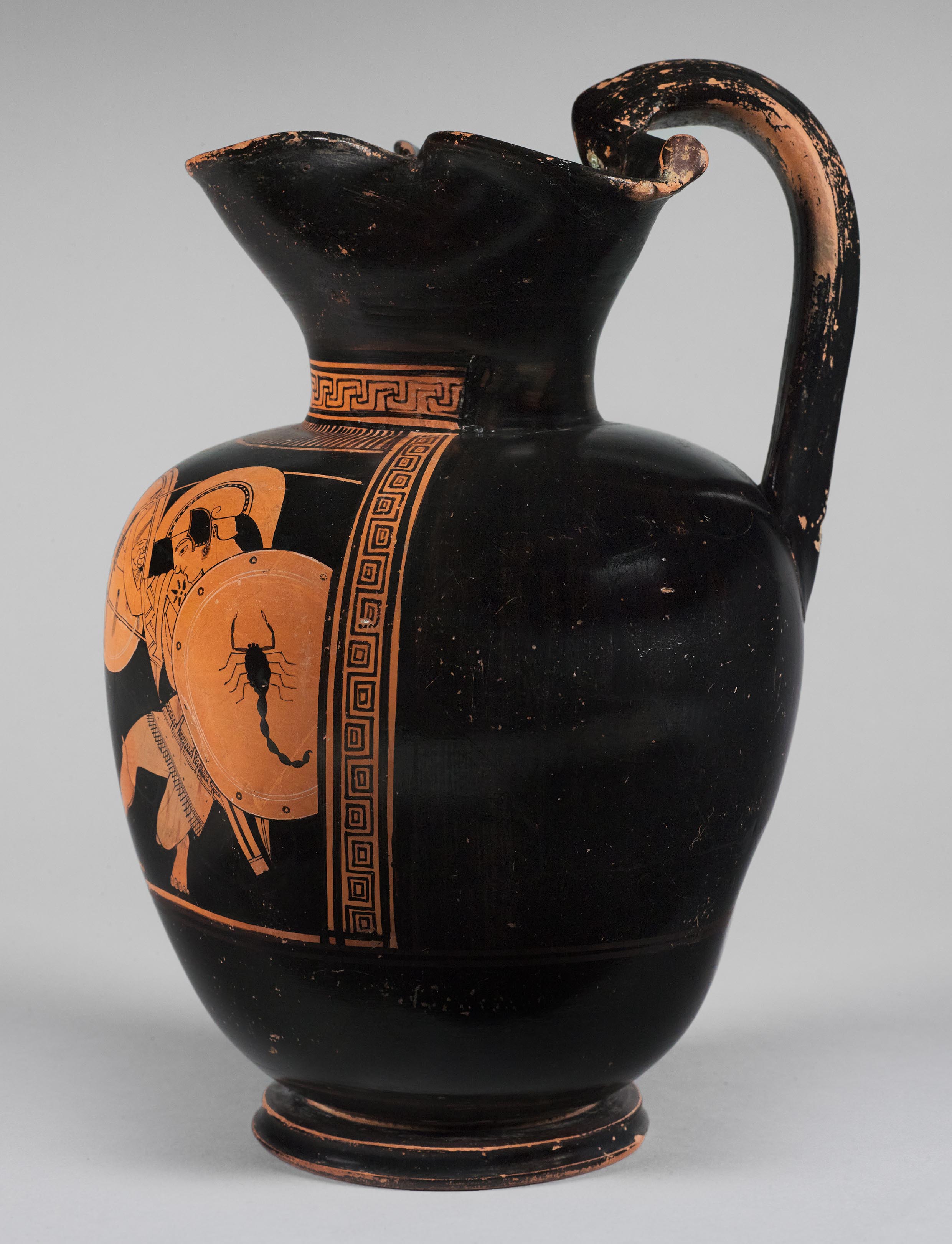

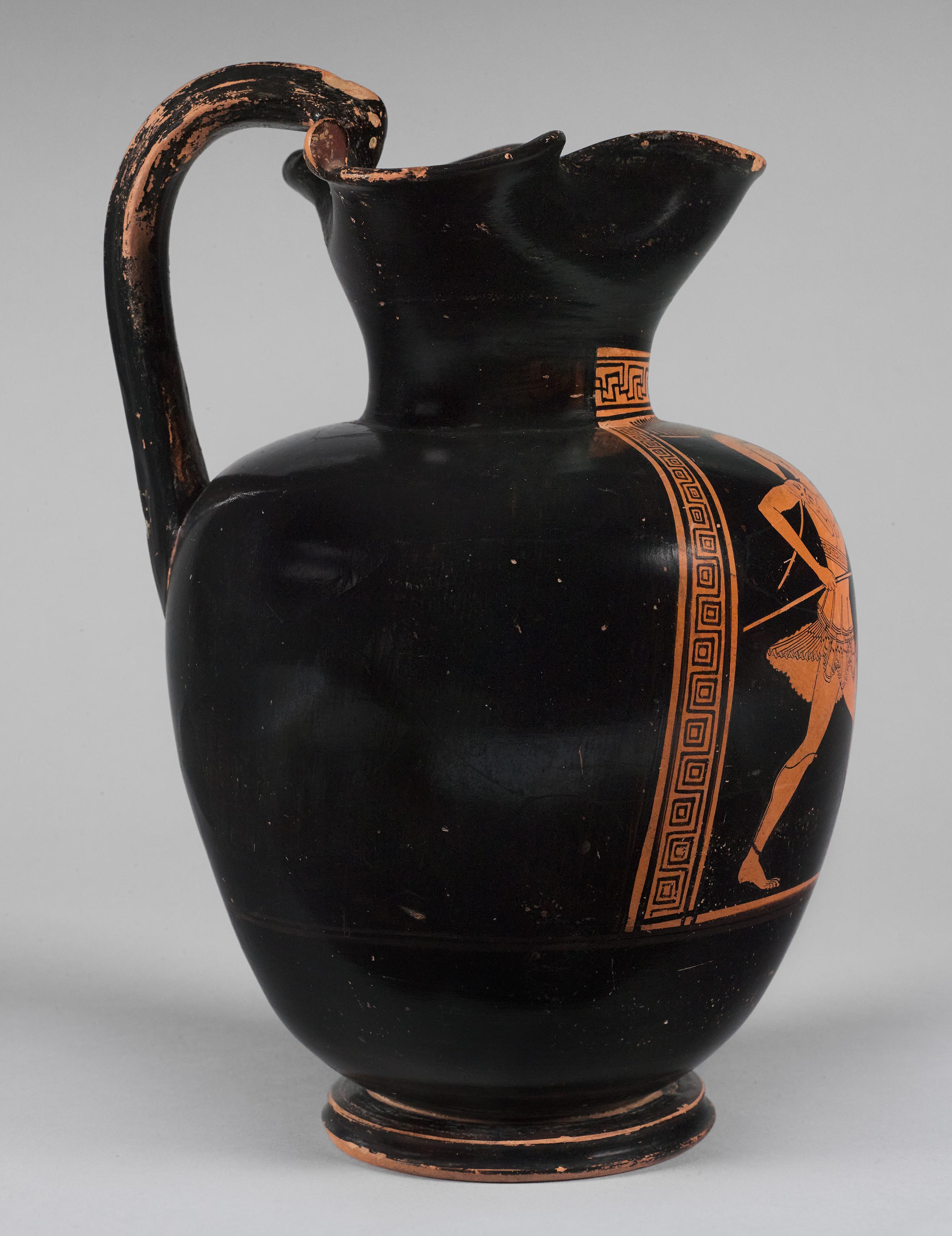

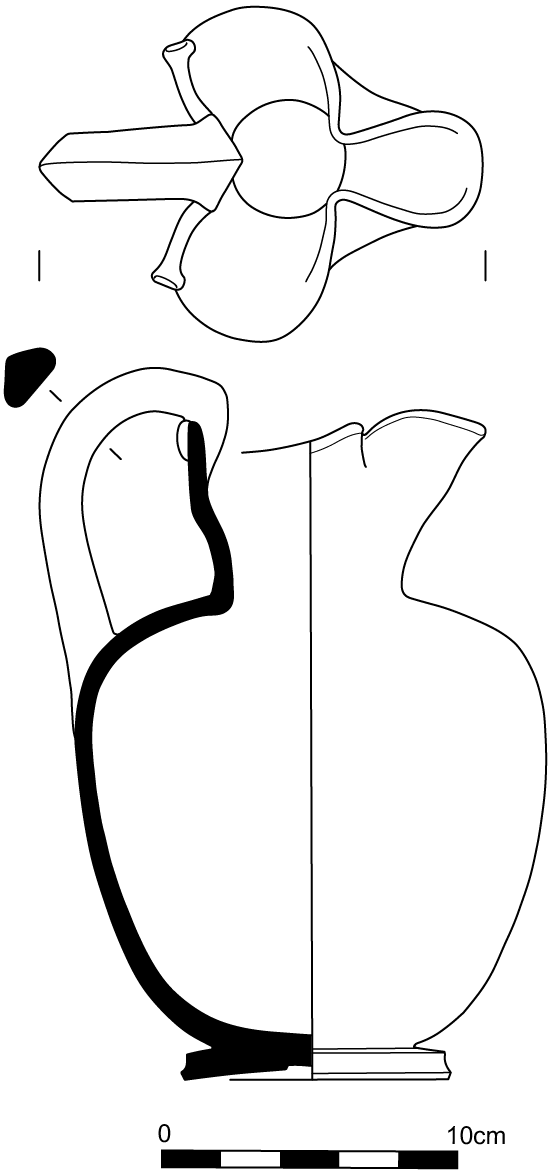

Trefoil mouth with slightly flaring lip. Interior of mouth and neck black. At bottom of neck, sloppily executed labyrinthine meander, framed by paired horizontal lines. Ridged handle, black, triangular in section, rising just above the mouth, with small rotelle, painted red, flanking the juncture. Tapering ovoid body. Figure panel framed laterally by embattled meanders framing concentric squares. Lateral frames constrict in width at the top, framed by vertical lines. Frieze of slender black tongues at top of figural panel. Reserved groundline. Pair of thin red bands circle the body below the groundline. Ring foot, with flat top, concave molding, and reserved underside—nearly flat, but slightly concave—with circular depression in the center (diam. 1.9 cm).

Subject

Duel between two beardless hoplite warriors. The warrior at the right falls backward, with both of his legs splaying diagonally in front of his upright torso. His left leg is flexed and foreshortened, concealing the lower leg behind the frontal thigh. His left foot and toes, including toenails and small wrinkles, are shown fully frontal and bear the entirety of his weight. His right leg extends in profile before him, barely flexed, with the right foot raised slightly off the ground. While falling, his head lolls downward and his eye rolls upward, intimating imminent death. The warrior has been wounded by his opponent’s spear, and red blood, now worn, flows from two pairs of wounds on his torso and left thigh. He wears greaves with ankle padding, the kneecap of which juts out from the frontal thigh of his left leg. The lappets of his cuirass are decorated with a dot pattern. The undergarment is decorated with crosses and lacks fold lines, perhaps suggesting the stiffness of leather, while its fringe consists of unhemmed, crosshatched lines. The one visible shoulder plate of the cuirass is decorated with a star. His Attic helmet has a raised black cheek flap which reveals sideburns beneath. He drapes a cloak over his right shoulder and carries a large round shield that covers most of his torso. The shield bears a black silhouetted scorpion device, placed within a pair of compass-drawn incised lines and a rim—also compass drawn—decorated with small circles. The shield is overlapped by the meander border at the right. The warrior’s scabbard extends beneath the shield, as does a pointed object with a central spine, presumably the point of his opponent’s spear. The location and angle of the spear point suggest that it has already pierced the warrior’s body and broken on contact with the shield. His own spear just misses the leg of his adversary, while the spear butt disappears beneath the meander border at the right.

The victorious warrior at the left charges forward to the right, with his left foot extended beyond the flailing right foot of his opponent. He has a wide stance, with both legs slightly bent. He thrusts the shield on his left arm forward, revealing its foreshortened interior and porpax (strap for the arm), the latter with a palmette flange. With his right arm bent and his right hand lowered to his waist, he jabs his spear into his opponent’s side, twisting his torso back in a three-quarter view. Unlike his opponent, he does not carry a sword. His greaves have ankle padding. His cuirass has plain lappets, and the shoulder flaps are decorated with stars and running animals. A frieze of embattled meanders framing squares runs across the midriff of the cuirass. Beneath the cuirass the warrior wears a chitoniskos with elaborate multiple folds, which swirls behind him, suggesting rapid movement. The crest of his Chalcidian helmet extends behind his back and beyond his right forearm.

Attribution and Date

Attributed to the Terpaulos Painter [J. Gaunt]. Circa 500–490 BCE.

Dimensions and Condition

h. 24.4 cm; diam. 15.7 cm; diam. of mouth (lateral) 11.3 cm; diam. of mouth (back to front) 8.3 cm; diam. of foot 9.3 cm. Broken and mended, but repaired in its entirety, aside from a small lacuna on the back of the vase, a section at the back of the trefoil mouth (both gaps restored in plaster), a chip on top of the handle, and a wide crack across the nose guard of the defeated warrior. Black gloss worn in places, in particular around the handle and the lip, suggesting heavy use. Modest repainting around some cracks, as well as on the victorious warrior’s lower leg, and most of the right foot of the defeated warrior. Handle reattached in antiquity using bronze pins, traces of which are preserved in four drill holes, three at the top and one at the base of the handle. Two shallow indentations in the body of the oinochoe, one around the thighs of the defeated warrior and the other on the reverse, made when the clay had not yet dried, presumably when someone in the workshop lifted the vase with one hand.

Technical Features

Preliminary sketch. Relief contours. Accessory color. Red: handle rotelle; stripes circling the body; inscriptions; blood; ankle padding. Dilute gloss: sternomastoids; leg muscles; and details on the defeated warrior’s foreshortened left foot.

Inscriptions

ΛYΣEAΣ KAΛOΣ (“Lyseas is handsome!”) to the right of the head of the victorious warrior, just beneath the tongue pattern. NAIXI (“Oh Yes!”) below the central shield and following the curve of the defeated warrior’s extended right leg; retrograde. HO ΠAIΣ KAΛOΣ (“The boy is handsome”) down the left side of the panel, behind the victorious warrior; retrograde.

Bibliography

Abbreviation: Princeton RecordRecord of the Princeton University Art Museum. (1942– ). 57 (1998): 196, 198 [illus.].

Comparanda

For the Terpaulos Painter, see Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 308; Abbreviation: ParalipomenaJ. D. Beazley. Paralipomena: Additions to Attic Black-Figure Vase-Painters and to Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. Oxford, 1971 357; Abbreviation: BAdd2Carpenter, T. H., ed. 1989. Beazley Addenda: Additional References to ABV, ARV2, and Paralipomena. 2nd ed. Oxford: Published for the British Academy by Oxford University Press. 212; D. C. Kurtz, Athenian White Lekythoi: Patterns and Painters (Oxford, 1975), 80, 95; W. G. Moon and L. Berge, Greek Vase-Painting in Midwestern Collections (Chicago, IL, 1979), 144–45. The Terpaulos Painter was first given his name by Beazley in a note on his inscriptions, with reference to an oinochoe of shape 2 in Rome (from Cerveteri), which depicts a satyr with the name Terpaulos, “the one who gives pleasure with the pipes”: Villa Giulia 2647 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 308.1; J. D. Beazley, “Some Inscriptions on Vases: VII,” Abbreviation: AJAAmerican Journal of Archaeology 61 (1957): 6, no. XII; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 203166). The Rome oinochoe also has a ridged handle and red rotelle. Although the isolated satyr is not framed laterally or above, the groundline consists of a frieze of embattled meanders framing concentric squares, similar to the lateral frames on Princeton’s oinochoe. The satyr on the oinochoe in Rome wears anklets in added red that resemble the greave pads of the warriors in Princeton. Another satyr given the name Terpaulos occurs on a vase in Berlin signed by Smikros: Berlin 1966.19 (Abbreviation: ParalipomenaJ. D. Beazley. Paralipomena: Additions to Attic Black-Figure Vase-Painters and to Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. Oxford, 1971 323.3 bis; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 352401). These are the only two vases bearing the name, and the similar subject and composition perhaps speak to a connection between the Terpaulos Painter and the Pioneers.

A third oinochoe of shape 2 attributed to the Terpaulos Painter, in Ceverteri, features ornamental designs similar to those found on Princeton’s oinochoe: Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 308.2; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 203167. The groundline on that oinochoe is painted as an embattled meander framing reserved squares, and the young victor on the body carries a ribbon bearing a labyrinthine meander like that on the neck of Princeton’s oinochoe. Variations of this type of meander were also popular within the workshop of the Pioneers, a further connection between the painter and this workshop.

A fourth oinochoe of this shape has been attributed to the Terpaulos Painter, also from Cerveteri and currently in the Villa Giulia (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 308.3, 1597; S. Muth, Gewalt im Bild: Das Phänomen der medialen Gewalt im Athen des 6. Und 5. Jahrhunderts v. Chr. [Berlin, 2008], 211, fig. 132; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 203168). This vase features the only other occurrence of the kalos name Lyseas, albeit here in black letters on a reserved groundline. The vase depicts a retreating hoplite, the details of which are very similar to those on Princeton’s oinochoe: cf. the folds of the warrior’s chitoniskos, which are carefully delineated with closely spaced relief lines; the long helmet crest; the frontal eye, open at the inner end, with the pupil toward the opening; and the careful drawing of the ear within the minimal space afforded by the helmet. The shield of the hoplite in Rome has been pierced by an arrow, another rare instance of a weapon shown penetrating a shield, like the spear on the Princeton jug. Although the cuirasses of the warriors in Rome and Princeton are of different types, they both bear friezes of embattled meanders framing reserved squares and leaping animals on the shoulder flaps.

Beazley suggested that a fifth oinochoe, of shape 1, was “probably” by the Terpaulos Painter: St. Louis 3283 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 308.4; Moon and Berge, Midwestern Collections, 144–45, no. 82; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 203169). It too shows a single figure, a maenad, surrounded by floral motifs. There is nothing in the figure drawing that would suggest separating this oinochoe from the others by the Terpaulos Painter, but there are no other females with whom to compare the maenad. The florals, which come to the front to frame the single figure, led Kurtz (Lekythoi, 80) to associate this oinochoe with the Berlin Painter and members of his circle, in particular the Dutuit Painter, a connection earlier noted by Jacobsthal: P. Jacobsthal, Ornamente griechischer Vasen (Frankfurt, 1927), 78. The Dutuit Painter decorated at least eight oinochoai, including four of shape 1: cf., with the oinochoe in St. Louis (supra), the florals on London E 511 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 307.9; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 203151). It is no coincidence that, in Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963, Beazley’s list of attributions to the Dutuit Painter is followed by that of the Terpaulos Painter.

A sixth vase was associated by Beazley with the Terpaulos Painter, a lekythos with warriors arming: Agrigento 23 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 308.5; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 203170). The shape is similar to the principal type decorated in the large black-figure workshop of the Sappho and Diosphos Painters, with which the Dutuit Painter was also associated: C. H. E. Haspels, Attic Black-Figured Lekythoi (Paris, 1936), 94. In addition, the neck florals are reminiscent of those on the body of the oinochoe in St. Louis (supra). Details of the figure drawing, however, including the curled nostrils and the drawing of drapery, as well as the crowded composition, suggest that this lekythos may not have been painted by the Terpaulos Painter himself.

Many features of the Princeton vase are relatively common in vase-painting of the Late Archaic and Early Classical periods. The scorpion device occurs on the shields of a wide range of individuals, including hoplites, hoplitodromoi, and barbarian warriors, suggesting that the motif does not have any particular iconographic significance: cf. a nearly contemporary cup attributed to the Proto-Panaetian Group, Paris, Louvre G 25 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 316.5, 1592; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 203243), which features a profile scorpion as a shield device for a young warrior; by the Nikosthenes Painter, Baltimore 48.2747 (S. Albersmeier, ed., The Art of Ancient Greece: The Walters Art Museum [Baltimore, MD, 2008], 76–77, no. 21; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 9023363), which shows a hoplitodromos in the tondo carrying a shield with a scorpion device; a column-krater once in Vienna attributed to the Eupolis Painter, formerly Vienna 640 (CVA Vienna 2 [Austria 2], pl. 93.4; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 13548), which depicts an Amazon bearing a shield emblazoned with a scorpion. Despite the occurrence of the motif on a range of figures, the scorpion may have been associated with ill omen and thus, perhaps, a fitting emblem for the defeated hoplite: see, for instance, E. Grabow, Schlangenbilder in der griechischen schwarzfigurigen Vasenkunst (Münster, 1998), 85–86; E. Anne Mackay, “The Baneful Hedgehog of Ancient Greece,” in Rich and Great: Studies in Honour of Anthony J. Spalinger on the Occasion of His 70th Feast of Thoth, eds. R. Landgráfová and J. Mynářová (Prague, 2016), 232–34. Alternatively, Rotroff has suggested a sympotic reading of the motif, albeit in connection with a stamnos that bears a scorpion playing the pipes as opposed to the more standardized scorpion shield devices: S. Rotroff, “A Scorpion and a Smile: Two Vases in the Kemper Museum of Art in St. Louis,” in Abbreviation: Athenian Potters and PaintersAthenian Potters and Painters: The Conference Proceedings. 3 vols. Vol. 1, edited by J. H. Oakley, W. D. E. Coulson, and O. Palagia. Oxbow Monograph 67. Vol. 2, edited by J. H. Oakley and O. Palagia. Vol. 3, edited by J. H. Oakley. Oxford, 1997 (vol. 1), 2009 (vol. 2), 2014 (vol. 3), vol. 3, 165–66.

For the apparent discrepancy between hoplite duels and actual warfare as conducted in the Late Archaic period, with the conclusion that such scenes represent an idealizing and heroizing attitude regarding the practice of war, see C. Ellinghaus, Aristokratische Leitbilder–Demokratische Leitbilder: Kampfdarstellungen auf athenischen Vasen in archaischer und frühklassischer Zeit (Münster, 1997), 95–155. For the view that hoplite duels are evidence for how warfare was actually perceived and psychologically experienced, see T. Hölscher, “Images of War in Greece and Rome: Between Military Practice, Public Memory, and Cultural Symbolism,” Abbreviation: JRSJournal of Roman Studies 93 (2003): 4–8. For the changing nature of Athenian military imagery in the Late Archaic and Early Classical periods, see J. Bažant, Les citoyens sur les vases athéniens du 6e au 4e siècle av. J.-C. (Prague, 1985), 7–12; Muth, Gewalt im Bild, 139–238; R. Osborne, The Transformation of Athens: Painted Pottery and the Creation of Classical Greece (Princeton, NJ, 2018), 93–116. The subject of dueling hoplites retained its popularity in the Late Archaic period, although it declined rapidly thereafter, with battles between hoplites and differently armed foes, including Persians and cavalrymen, replacing hoplites fighting one another. For the changing relationship and frequency of depictions of hoplites and other warriors, such as cavalrymen, peltasts, and barbarians, see F. Lissarrague, L’autre guerrier: Archers, peltastes, cavaliers dans l’imagerie attique (Paris, 1990). Images of single hoplites also decline in popularity, with more than three-quarters of such compositions occurring on pots painted before 480. Nevertheless, the single hoplite remains popular with some artists and workshops, such as the Berlin Painter: cf. Vienna 654 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 201.67; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 201875). Far more popular at this time are scenes of arming and departing warriors. For the argument that the decline in the popularity of dueling hoplites in the Archaic period and the increasing popularity of arming scenes in the Classical period represents a shift from Archaic individuality to Classical collectivity, see Osborne, Transformation of Athens, 87–121. The equal attention given on Princeton’s vase to both victor and victim shows an increased concentration on the losing hoplite in this period, with a more overt example being the hoplite on the oinochoe in Rome by the Terpaulos Painter (supra), who flees before a hail of arrows. For the argument that the more explicitly violent and sympathetic treatments of the losing hoplite are a response to the Athenians’ actual experience of war, such as with the Persians, see Ellinghaus, Aristokratische Leitbilder, 95–155. Muth (Gewalt im Bild, 182–214) has recently shown that this development takes place well before major Athenian military conflicts, arguing instead that the scenes describe and intensify an agonal ethos in Athens predicated on the display of a spectrum of strength.

The generic “ho pais kalos” inscription is far more common than those naming particular youths, allowing the viewer to associate the inscription freely with an individual of his choice, or with the figural decoration. For a discussion of the function of this inscription as a reference both to the depicted imagery and perhaps to a symposiast viewing and reading the inscription, see F. Lissarrague, “Publicity and Performance: kalos Inscriptions in Attic Vase-Painting,” in Performance Culture and Athenian Democracy, eds. S. Goldhill and R. Osborne (Cambridge, UK, 1999), 357–73. “Naixi” usually occurs alongside kalos inscriptions and presumably serves as an affirmative to the designation of beauty, as is made clear when it immediately follows the kalos inscription: cf., e.g., the Berlin Foundry Cup, Berlin F 2294 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 400.1; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 204340). The affirmative exclamation can also be separated from the kalos inscription, perhaps suggesting a response to the praise: cf. Naples 86331 (Abbreviation: ABVJ. D. Beazley. Attic Black-Figure Vase-Painters. Oxford, 1956 678; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 306485); London E 52 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 432.59; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 205104).