Provenance

1955, sale, Münzen und Medaillen AG (Basel) to Princeton University.

Shape and Ornament

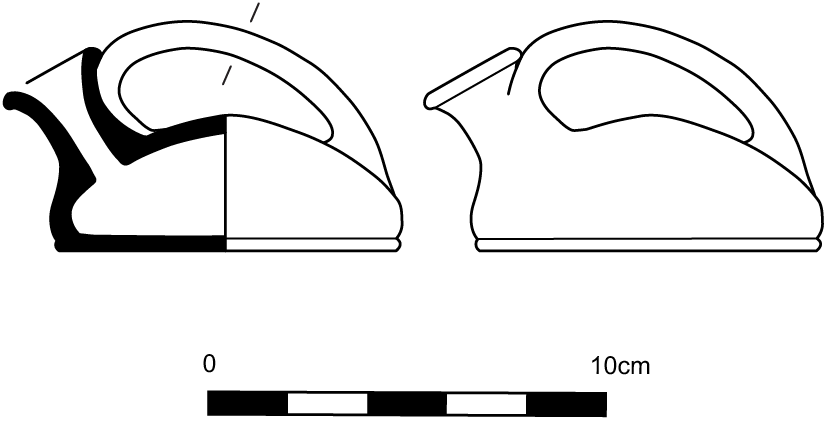

Round, shallow body, black, with convex walls forming a low, domed upper surface. Narrow-necked, flaring spout rising obliquely from the shoulder. Interior of spout and neck black. Black strap handle, flattened oval in section, extending from back of spout to opposite shoulder. Continuous reserved stripe serves as a groundline for figural decoration. Slender torus ring base, with flat, reserved underside.

Subject

Lion and boar. The growling lion, with its tongue sticking out, stands to the left of the spout, facing it. Its four feet are on the ground, and its tail curls behind its hind legs. The boar faces the lion on the opposite side, also braced on all four legs and awaiting its opponent with tusks bared.

Attribution and Date

Attributed to the Group of Agora P5562 [J. D. Beazley]. Circa 470 BCE.

Dimensions and Condition

h. 5.8 cm; w. 10.1 cm; diam. 8.9 cm; diam. of mouth 0.4 cm; diam. of foot 8.8 cm. Intact. Black gloss rather matte. Wear and abrasion overall, in particular on the handle and around the mouth of the spout. Minor incrustation on the bottom surface.

Technical Features

Preliminary sketch. Relief contours. Accessory color. Dilute gloss: ridges on boar’s back, its bristly hide, and details of its snout; mane and ribs of lion. Reserved areas apparently received only a faint wash of miltos and are consequently a pale, reddish buff.

Bibliography

Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 776.1; Münzen und Medaillen AG, Basel, Auction Sale XIV, Classical Antiquities, June 19, 1954, no. 79, pl. 17; H. Hoffmann, Sexual and Asexual Pursuit: A Structuralist Approach to Greek Vase Painting (London, 1977), 11, no. 27, pl. 2.4; Ancient Art: The Development of the Greek and Roman Figural and Animal Styles, exh. cat., Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Museum, Rutgers University (New Brunswick, NJ, 1981), 20–21; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 209577.

Comparanda

For the Group of Agora P 5562, see Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 776–77; Abbreviation: BAdd2Carpenter, T. H., ed. 1989. Beazley Addenda: Additional References to ABV, ARV2, and Paralipomena. 2nd ed. Oxford: Published for the British Academy by Oxford University Press. 288. The name-vase of the Group also features a carefully drawn boar: Athens, Agora P 5562 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 777.2; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 209578). The details of the boar are very similar to those on Princeton’s asksos: cf., in particular, the execution of the eye with a long tear duct, the high arching hook of the shoulder contour, the protruding nasal tip, and the dilute gloss for the bristles. Beazley (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 777) suggested that “the two may be by one hand.” Hoffmann listed another askos with a boar and opposing lion as being from the Group, but it is clearly later and unrelated: Milan 3643.14 (Hoffmann, Pursuit, 11, no. 25, pl. 17.3; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 13940). Beazley (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 777, top) thought two other vessels, each featuring donkeys, were “akin” to the Group of Agora P 5562, but the connection is difficult to discern: askos New York 23.160.57 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 971.6; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 213226); chous Munich SH 2469 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 971; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 213228).

For askoi, see J. D. Beazley, “An Askos by Macron,” Abbreviation: AJAAmerican Journal of Archaeology 25 (1921): 325–36; B. A. Sparkes, L. Talcott, and G. M. A. Richeter, Black and Plain Pottery of the 6th, 5th, and 4th Centuries B.C.: Part 1; Text, Abbreviation: AgoraAthenian Agora (Princeton 1953– ) 12 (Princeton, NJ, 1970), 157–60; Hoffmann, Pursuit, 1; L. Massei, Gli askoi a figure rosse nei corredi funerari delle necropoli di Spina (Milan, 1978); Abbreviation: Robertson, Art of Vase-PaintingM. Robertson, The Art of Vase-Painting in Classical Athens. Cambridge, 1992, 105–6; M. B. Moore, Attic Red-Figured and White-Ground Pottery, Abbreviation: AgoraAthenian Agora (Princeton 1953– ) 30 (Princeton, NJ, 1997), 55–57. In his 1921 publication, Beazley identified eleven different types of askoi, while in Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 he seems to have modified these groups into two, with one characterized by a low body and the other by a tall body. In order to avoid confusion with Beazley’s multiple numbering systems, Sparkes and Talcott (Abbreviation: AgoraAthenian Agora (Princeton 1953– ) 12) simplified the groups into shallow and deep askoi, with variations, a system followed subsequently by Moore (Abbreviation: AgoraAthenian Agora (Princeton 1953– ) 30). The earliest Attic red-figure askoi are deep, with high sides and flat tops; these are often ring-shaped, perhaps inspired by ring-askoi from East Greece, where they were a staple. A trio of early deep askoi from a shipwreck off Sicily have been attributed to Epiktetos: Gela 36349, 36350, 38007 (D. Paleothodoros, Épictétos [Namur, 2004], nos. 141–43, pls. 41, 42.2, 43.1–2; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 18431, 18610, 9033918). Further early examples have been attributed to the Painter of Berlin 2268 (Paris, Louvre G 609: Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 157.89; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 201495) and to Makron (Providence 25.074: Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 480.338; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 205021). Makron also painted an early shallow askos, like the one in Princeton, which became the canonical layout: Brunswick 1923.30 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 480.339; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 205022). The shallow askos steadily increases in popularity throughout the fifth century, with the handle rising increasingly high, and with the high dome seen on Makron’s shallow askos falling out of fashion. Proportions of askoi tend to become broader and lower moving through the fifth century. However, the development of the shape was not strictly linear. Although this askos does not have a high dome, its low handle and, more importantly, its figural style, place it relatively early in the development of figured askoi. On later askoi, the nipple on the upper surface is articulated into a molding that simulates a lid: cf. Athens, Agora P 1856 (Hoffmann, Pursuit, 11, no. 14, pl. 1.4; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 5753).

As noted by Hoffmann (Pursuit, 3), pairings of animals often juxtapose “natural animals,” such as boars and lions, which are paradigmatic adversaries in poetic similes. For Hoffmann, themes of the chase relate to the “betwixt and between” character of sacrifice, making them suitable for a shape that he believes to have been primarily intended as a libation vessel for the tomb. Barringer, although focused on human hunting scenes, emphasizes the metaphoric significance of pursuit scenes in general, which often allude to the heroic arete and are thus appropriate for a funerary setting: J. M. Barringer, The Hunt in Ancient Greece (Baltimore, MD, 2002), 10–69. In Homeric similes, boars are often symbolic of a defeated but worthy enemy, with lions identified as the deadliest of adversaries: C. Sourvinou-Inwood, “Reading” Greek Death: To the End of the Classical Period (Oxford, 1995), 226. See also, for further funerary and heroic discussions of lion pursuits, F. Hölscher, Die Bedeutung archaischer Tierkampfbilder (Würzburg, 1972); G. Markoe, “The ‘Lion Attack’ in Archaic Greek Art: Heroic Triumph,” Abbreviation: ClAntClassical Antiquity 8 (1989): 86–115. For more on the significance of boars in Greek culture, see L. Calder, Cruelty and Sentimentality: Greek Attitudes to Animals, 600–300 BC (Oxford, 2011), 76–77. However, as noted by Boardman, many decorated askoi found in Athens come from domestic contexts, and scenes of libation on contemporary Athenian vases never show askoi in use. The shape itself, which produces two semicircular fields, lends itself to quadruped animals, which, when depicted in general on various shapes, are often involved in some form of pursuit or hunt: J. Boardman, “Betwixt and Between,” Abbreviation: CRThe Classical Review 29 (1979): 118–20. Furthermore, the form of the spout, with its narrow opening, is likely indicative of its function as an oil, rather than wine, container. It has also been suggested that askoi could have been used for vinegar: see, most recently, I. McPhee, “The Red-Figured Pottery from Torone, 1981–1984: A Conspectus,” Abbreviation: MeditArchMediterranean Archaeology: Australian and New Zealand Journal for the Archaeology of the Mediterranean World 19–20 (2006): 129–30. For a recent overview of animal fight scenes, with a focus on how the wild otherness of animals, as expressed through the depiction of bodies and postures, serves as a means to define the human self, see C. Beier, “Fighting Animals: An Analysis of the Intersections between Human Self and Animal Otherness on Attic Vases,” in Interactions Between Animals and Humans in Graeco-Roman Antiquity, eds. T. Fögen and E. Thomas (Berlin, 2017), 275–304.