Provenance

By 1963, Paris art market (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 145); 1995, Christie’s (London); 1995–2019, Walter Gilbert (Cambridge, MA); 2019, sale, Walter Gilbert via Phoenix Ancient Art (New York, NY) to Princeton University.

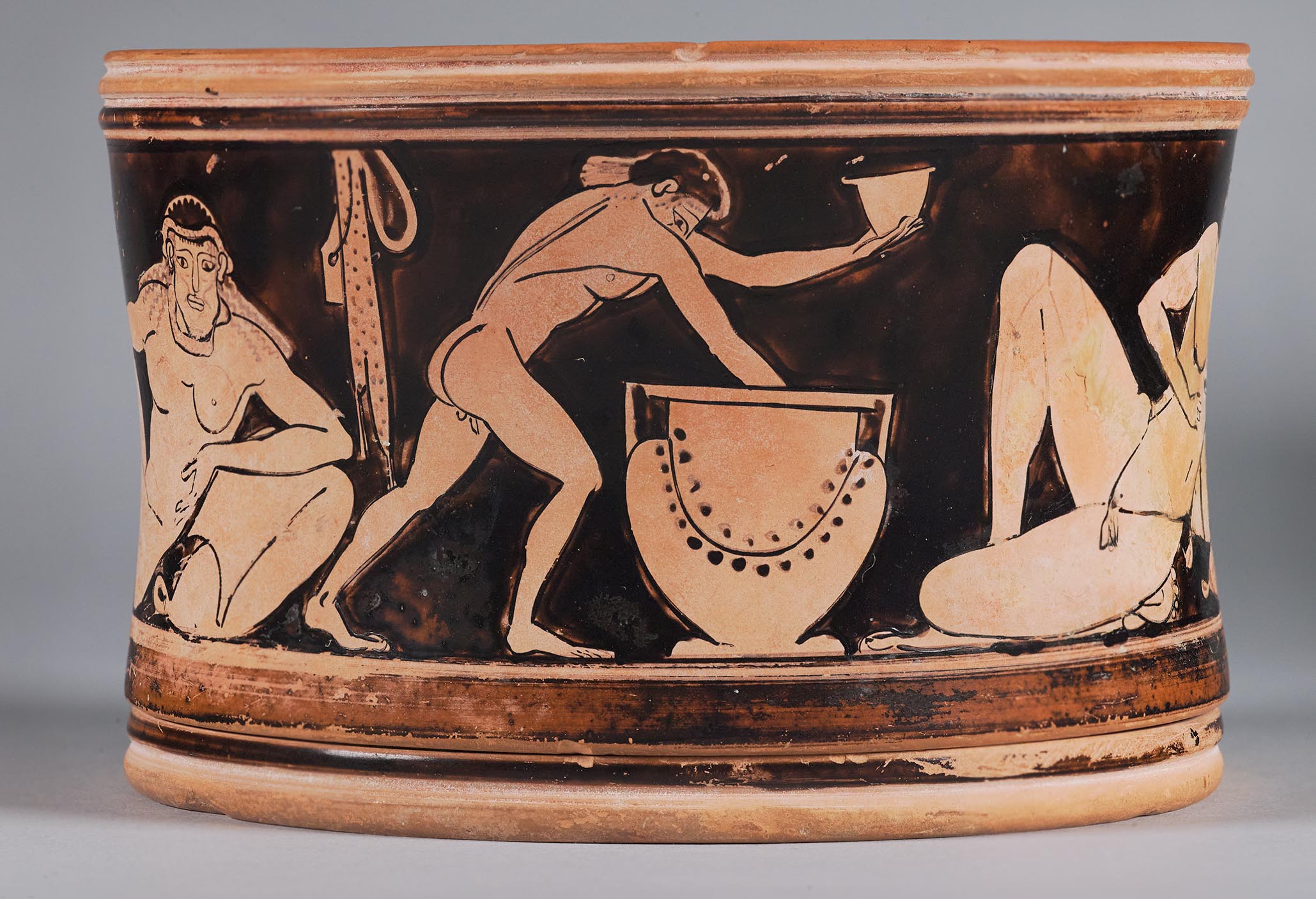

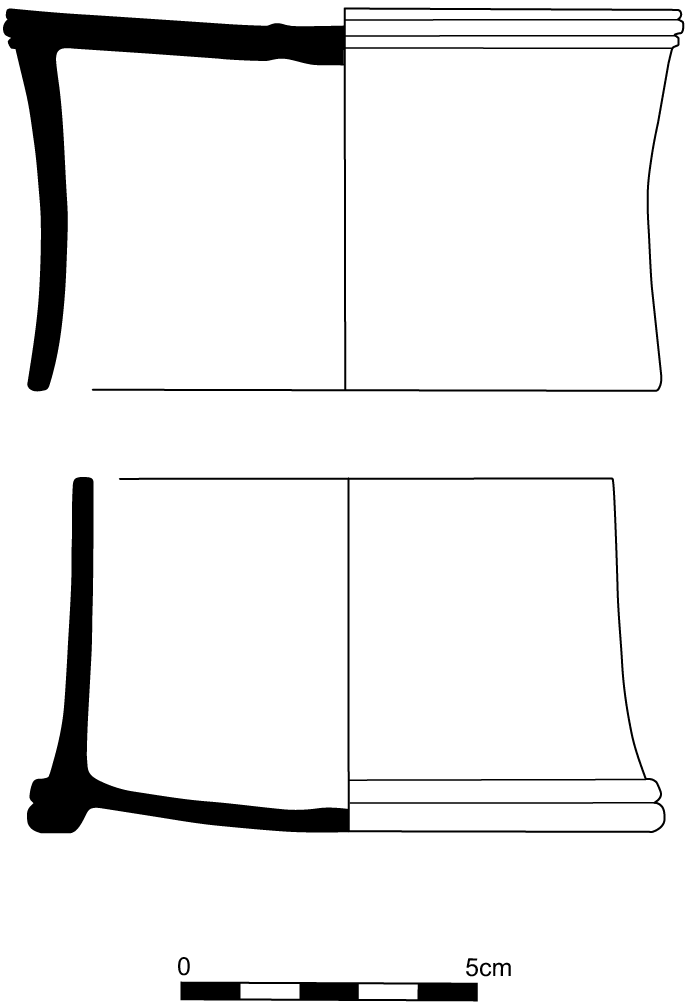

Shape and Ornament

Lid. Cylindrical, with tall, concave walls and a slightly concave upper surface. Interior black. Double-grooved molding at upper edge. On top, five palmettes—four with seven fronds, one with six—enclosed by a single coiling tendril, all contoured with relief lines. Palmette hearts consist of a small black dot encircled by a reserved band. Small reserved rings and buds in interstices between palmettes. The central disk on top decorated with chariot wheel. The figure frieze around the lid is framed above and below by simple reserved stripes.

Body. Cylindrical, with flat floor, walls tapering inward to avoid contact with the lid. Grooved flange around the base, on the black surface of which the lid rests. Exterior painted with six broad, black stripes; interior black. Underside slightly recessed and reserved, with five concentric circles of varying thicknesses. Inner surface of the flange black. Reserved resting surface.

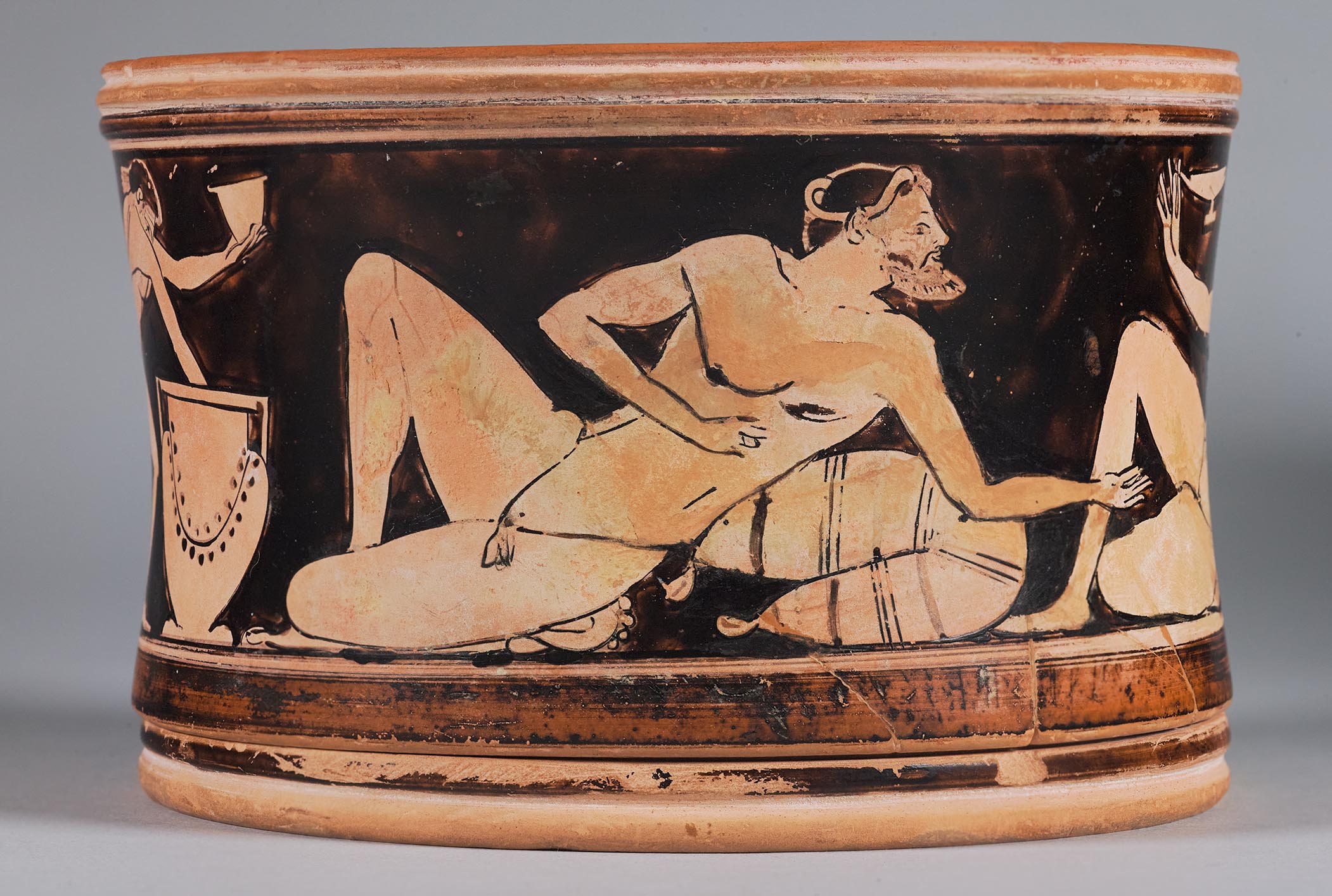

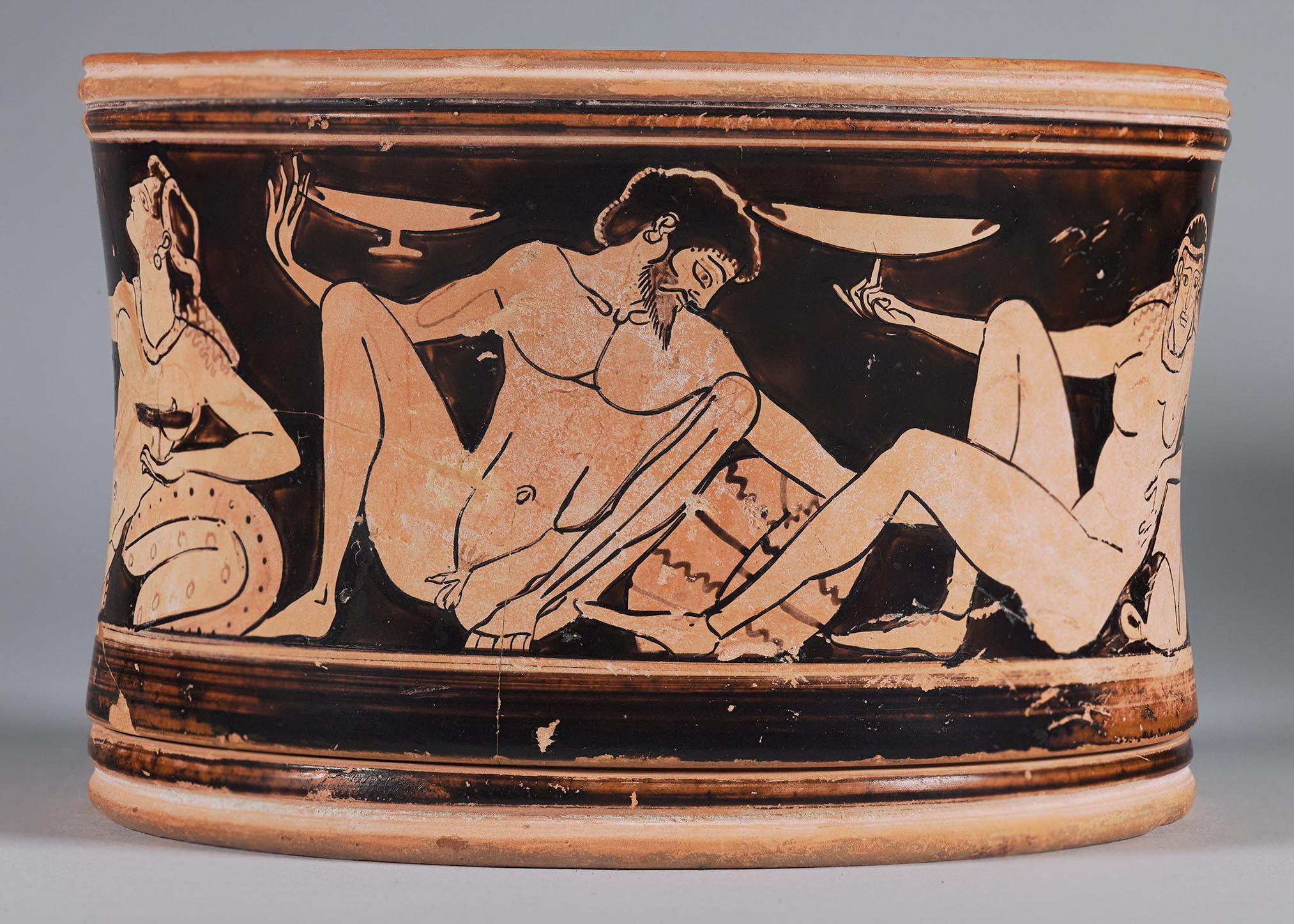

Subject

Symposion. Five figures participate in a symposion, all nude: two women, certainly hetairai; two mature, bearded men; and a beardless youth. One hetaira looks directly out at the viewer with a frontal face. She wears slippers and a padded, dotted fillet around her brow and neck. She reclines on a folded wineskin, her posture relaxed, with her right leg flexed and her left leg extending far to the left while her torso twists in a three-quarter view, with one breast frontal and the other in profile. In her raised right hand she clutches a kylix by the foot. To her right hangs a dotted sybene, a case for the auloi (double pipes) not currently in use. To the right of the sybene, a nude boy, drawn on a much smaller scale than the reclining symposiasts, stands with his right leg thrust forward and his left leg extending behind him. He bends over to reach his right arm into a garlanded column-krater to fill the skyphos in his raised left hand. His head is shown profil-perdu, with his right shoulder concealing his nose and mouth. To the right of the krater, a nude, bearded male symposiast with a padded fillet in his hair reclines against a striped cushion. His right leg is drawn up with his foot flat on the ground, while his left leg is tucked beneath him, the sole of his foot visible behind his hip, boldly foreshortened and facing the viewer. It is unclear whether he held a cup in his repainted right hand; the cup held by the enslaved boy may be his. His upper body is shown frontal and his head in profile to the right as he twists around to address his female companion, extending his left arm toward her loins. The naked hetaira reclines to the right on a dotted cushion, with her legs drawn up in the same way as the man. She wears padded fillets around her brow and neck, like the other female symposiast, as well as an earring. Although her torso is nearly frontal, her right breast is drawn in profile, and the left breast is fully frontal. She tilts her head sharply upward, avoiding the gaze of the man as she prepares for a kottabos toss, ready to fling the dregs from the kylix that she twirls on her right index finger. She balances a second kylix, painted black, on the palm of her left hand. To the right, a second naked and bearded man sits, or rather squats, by a cushion decorated with straight and wavy bands. Both of his legs are drawn up, his knees spread wide to expose his full nakedness and his frontal torso. His right leg is drawn in profile, while his left is frontal and foreshortened, the thigh depicted with unnatural slenderness. He, too, plays kottabos, twirling a kylix on the fingers of his raised right hand, but he does not face his target. Instead, he turns his head in profile to the right to face the first, frontally faced hetaira, reaching toward her crotch, his left hand disappearing between her legs. The central position of this woman in the composition is signaled by not only her frank gaze but also her proximity to the sympotic instruments: wineskin, pipe case, krater, enslaved youth.

Attribution and Date

Unattributed. Circa 510–490 BCE.

Dimensions and Condition

Lid: h. 6.5 cm; diam. 11.4 cm. Body: h. 6.0 cm; diam. of base 10.9 cm. Body unbroken, with minor chips along the flange, where some of the black gloss is worn. Minor incrustration along the upper surface of the flange. Lid broken and mended. Careless repainting along some of the breaks, especially on the man to the right of the column krater—his chest, belly, and both arms—and the woman to his right, especially her right lower leg and right shoulder.

Technical Features

Relief contours throughout, except for hair. Accessory color. Red: inscriptions. Dilute gloss: musculature and anatomy throughout, in particular abdomens, calves and thighs, kneecaps, biceps; beards; curly tresses of the women and hair fringe of the men; cheeks of the frontally faced woman; the eyelashes of the second woman and the circles on her cushion; dots on the sybene.

Inscriptions

HO ΠAIS KAΛOS three times, orthograde; faded but visible in raking light. Starting under the serving boy’s left arm: H O [Π] A I S K [A] Λ O S. Starting by the head of the woman preparing for a kottabos toss, going down along the squatting man’s right leg and under his genitals: [H] O Π A I S K A Λ O [S]. Starting above the cup held by the frontally faced woman: H O [Π] A I S [K A] Λ O S.

Bibliography

Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 145; F. Frontisi-Ducroux, Du masque au visage: Aspects de l’identité en Grèce ancienne (Paris, 1995), pl. 87; J. M. Eisenberg, “Summer 1995 Antiquities Sales: A report of the London and New York acutions,” Minerva 6 (1995): 31, fig. 24; Christie’s, Fine Antiquities, auc. cat., July 5, 1995, London, 75–76, lot 170; C. Houser, From Myth to Life: Images of Women from the Classical World, exh. cat., Smith College Museum of Art (Northampton, MA, 2004), 78–81, no. 31; Phoenix Ancient Art, The Gilbert Collection, auc. cat. (New York, NY, 2019), 56–57, no. 106; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 201287.

Comparanda

Beazley (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 145) first associated the pyxis with the Chaire Painter, noting that it “is more elaborate than any known work of the painter, but like him.” His hesitation is telling, and subsequent study of the pyxis has failed to reach a definitive attribution, as it has also been associated with the Painter of Berlin 2268 and the Bryn Mawr Painter (Christie’s, Fine Antiquities, auc. cat., July 5, 1995, London, 75–76, lot 170). Although the type B pyxis is quite rare in red-figure, with no painter specializing in the shape, Roberts notes that throughout the fifth century the great majority of artists who paint pyxides specialize in cups: S. Roberts, The Attic Pyxis (Chicago, IL, 1978), 23. Moore suggests that Princeton’s pyxis is the earliest example of the shape in red-figure, with a majority of the attributed examples of type B dating to the second half of the fifth century and later: M. B. Moore, Attic Red-Figured and White-Ground Pottery, Abbreviation: AgoraAthenian Agora (Princeton 1953– ) 30 (Princeton, NJ, 1997), 52. The anatomical renderings, subtly articulated with dilute gloss, the extensive use of relief contour, and the varied and foreshortened postures certainly place the piece in the Late Archaic period, carrying on the stylistic tradition of the Pioneers and Onesimos. Cf., e.g., the buxom, frontally faced hetaira on Euphronios’s psykter in the Hermitage, St. Petersburg B 1650 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 16.15, 1619; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 200078); the female kottabos game on the shoulder of a hydria by Phintias, Munich SH 2421 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 23.7, 1620; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 200126); the two male symposiasts in the tondo of a cup attributed to the Proto-Panaetian Group, Boston 01.8018 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 317.9, 1577, 1645; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 203247), which Beazley (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 317.9) felt “may really be an early work by the ‘Panaitios Painter,’” (i.e., Onesimos).

Of the painters associated to date with Princeton’s pyxis, none offer sufficient parallels for attribution. The Chaire Painter does paint several similar profil-perdu youths (e.g., Heidelberg 61 and the joining Vatican 22961: Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 144.1; Abbreviation: BAdd2Carpenter, T. H., ed. 1989. Beazley Addenda: Additional References to ABV, ARV2, and Paralipomena. 2nd ed. Oxford: Published for the British Academy by Oxford University Press. 178; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 201273), as does the Painter of Berlin 2268 (e.g., Christie’s, Fine Antiquities, auc. cat., June 16, 2006, New York, NY, no. 112; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 9019243), artists whom Beazley placed in his “Coarser Wing” of early red-figure cup-painters. The anatomical renderings, however, are clearly distinct: cf., for instance, the rounded collar bones on Princeton’s pyxis, with the angular clavicle on a cup by the Chaire Painter: Leipzig T 3578 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 145.9; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 201282). The downturned lip and wide, profile eye of the symposiast on Leipzig T 3578 resembles the profile-faced female on the Princeton pyxis, albeit less precise in execution and lacking the fine dilute gloss eyelashes, rare in this period and within the larger Coarser Wing. The standing, bearded man on an alabastron by the Painter of Berlin 2268 offers a relatively close parallel for the face and anatomical detailing of the squatting man with a frontal torso, particularly in the treatment of the clavicles and the abundant use of dilute gloss, including for the sternomastoid muscle: once London market (Sotheby’s, Antiquities, auc. cat., May 23, 1991, London, no. 70; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 275074). However, the draftsmanship is once again not as detailed or ambitious as on the Princeton pyxis, and the Painter of Berlin 2268 tends to reserve most of the contours of his figures. Such similarities to the Chaire Painter and the Painter of Berlin 2268 do, however, suggest that the pyxis should be placed in Beazley’s larger Coarser Wing, more aligned with the boldness and expressiveness of Onesimos, albeit at a reduced level of expertise. Cf. the more languid and relaxed male symposiast by the Bryn Mawr Painter in the tondo of his name-vase: Bryn Mawr P 95 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 456.1; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 216736).

For the connection with Onesimos and the Proto-Panaetian Group, the cup in Boston (supra) offers a number of useful parallels, such as the bold frontal poses, with foreshortened feet and shins, the relief-line iliac crest, the dilute-gloss abdomen, and the hooked clavicles. One should perhaps not speak of a direct connection between Onesimos and the painter of Princeton’s pyxis, but rather of distant and not entirely successful emulation. Although the rendering of the hetaira’s frontal face lacks clear stylistic parallels, Onesimos also occasionally drew frontally faced figures with similarly angular features, albeit narrower and with tighter lips: cf. Paris, Louvre Cp 12514 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 322.36; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 203286). For the influence of the Pioneer Group and Onesimos on the painters of the Coarser Wing and their own followers, including the Bonn Painter, see Abbreviation: Robertson, Art of Vase-PaintingM. Robertson, The Art of Vase-Painting in Classical Athens. Cambridge, 1992, 39, 109–10.

For type B pyxides, see B. A. Sparkes, L. Talcott, and G. M. A. Richeter, Black and Plain Pottery of the 6th, 5th, and 4th Centuries B.C.: Part 1; Text, Abbreviation: AgoraAthenian Agora (Princeton 1953– ) 12 (Princeton, NJ, 1970), 174–75; Roberts, Attic Pyxis, 3–5. In later examples of the shape in red-figure, the top of the lid is often decorated with a woman’s head, and only rarely is the space given over to pure ornament: cf., by the Painter of the Louvre Centauromachy, Paris, Louvre CA 587 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 1094.104, 1682; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 216046). The banded decoration of the body is without parallel among red-figure pyxides of type B. Such banding does occur, sporadically, on other shapes in black-gloss ware: cf. an olpe from the Athenian Agora, Athens, Agora P 12552 (Abbreviation: AgoraAthenian Agora (Princeton 1953– ) 12, pl. 12, no. 254); a lekythos from the Athenian Agora, Athens, Agora P 24532 (Abbreviation: AgoraAthenian Agora (Princeton 1953– ) 12, pl. 38, no. 1114); a neck-amphora in Barcelona, which also has black palmettes, Barcelona 1481 (Abbreviation: ABVJ. D. Beazley. Attic Black-Figure Vase-Painters. Oxford, 1956 600.3; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 305986). All three examples date to the end of the sixth or early fifth century.

Nude women attending symposia alongside male companions are usually identified as hetairai, with the assumption that the exclusion of respectable wives was central to sympotic functioning: see Abbreviation: Peschel, HetäreI. Peschel. Die Hetäre bei Symposium und Komos in der attisch rotfigurigen Malerei des 6.–4. Jhs. v. Chr. Frankfurt, 1987; O. Murray, “Sympotic History,” in Abbreviation: SympoticaSympotica: A Symposium on the Symposion. Edited by O. Murray. Oxford, 1990, 6; J. Neils, “Others within the Other: An Intimate Look at Hetairai and Maenads,” in Abbreviation: Not the Classical IdealNot the Classical Ideal: Athens and the Construction of the Other in Greek Art. Edited by B. Cohen. Leiden, 2000, 204–5; S. Lewis, The Athenian Woman: An Iconographic Handbook (New York, 2002), 112; S. Corner, “Bringing the Outside In: The Andrōn as Brothel and the Symposium’s Civic Sexuality,” in Greek Prostitutes in the Ancient Mediterranean, 800 B.C.E.–200 C.E., eds. A. Glazebrook and M. M. Henry (Madison, WI, 2011), 60–85; id., “Did ‘Respectable’ Women Attend Symposia?” Abbreviation: GaRGreece and Rome 59 (2012): 34–45. Indeed, attendance at a symposion is generally considered the most reliable iconographical sign for the identification of hetairai. For the counterargument, that respectable women did attend symposia, or other less formal drinking parties, see J. Burton, “Women Commensality in the Ancient Greek World,” Abbreviation: GaRGreece and Rome 45 (1998): 143–65; C. Kelly Blazeby, “Women + Wine = Prostitute in Classical Athens?” in Greek Prostitutes, eds. Glazebrook and Henry, 86–105.

On the difficulty of equating nudity with prostitution in general, see M. F. Kilmer, Greek Erotica on Attic Red-Figure Vases (London, 1993), 159–67; G. Ferrari, Figures of Speech: Men and Maidens in Ancient Greece (Chicago, IL, 2002), 11–60; Lewis, Athenian Woman, 101–12; U. Kreilinger, “To Be or Not to Be a Hetaira: Female Nudity in Classical Athens,” in Images and Gender: Contributions to the Hermeneutics of Reading Ancient Art, ed. S. Schroer (Fribourg and Göttingen, 2006), 229–37. For the suggestion that female symposiasts are meant to invoke the Athenian’s distant past, at a time when women did attend symposia, see K. Topper, The Imagery of the Athenian Symposium (Cambridge, UK, 2012), 105–35. Topper (ibid., 23–52) also argues that symposia without couches, such as that on Princeton’s pyxis, represent contemporary Athenians’ views of the symposion of their distant past, but we may question whether these naked revelers brought to mind the venerable ancestors of contemporary Athenians. The boy stands on the same groundline as the banqueters, suggesting that they are on the ground, but it is just as likely that the painter simply omitted the klinai in order to draw figures of reasonable size.

On Princeton’s pyxis, as in other depictions of female symposiasts, the women act like male drinkers, reclining and playing kottabos, and even resemble men in terms of their heavy builds; indeed, the men seem almost puny in comparison. For the symmetry of male and female roles in mixed-gender sympotic scenes, see Abbreviation: Peschel, HetäreI. Peschel. Die Hetäre bei Symposium und Komos in der attisch rotfigurigen Malerei des 6.–4. Jhs. v. Chr. Frankfurt, 1987, 71; P. Schmidt-Pantel, La cité au banquet: Histoire des repas publics dans les cités grecques (Rome, 1992). For the argument that such vases assimilate the female hetaira to men to create an ideologically charged fantasy-image of a symposion of equals, see L. Kurke, “Inventing the ‘Hetaira’: Sex, Politics and Discursive Conflict in Archaic Greece,” Abbreviation: ClAntClassical Antiquity 16 (1997): 118; R. Neer, Style and Politics in Athenian Vase Painting: The Craft of Democracy, ca. 530–460 B.C.E. (Cambridge, UK, 2002), 106.

Symposia rarely occur on any type of pyxis, which is not a sympotic vessel, but rather a receptacle for trinkets and jewelry. A majority of pyxides are thus decorated with domestic scenes, with numerous examples associated with woman’s festivals, such as those found at Brauron: L. Ghali-Kahil, “Quelques vases du sanctuaire d’Artemis à Brauron,” Abbreviation: AntKAntike Kunst, Suppl. 1 (1963): 5–29. For the iconography of the pyxis, see Roberts, Attic Pyxis, 177–87; S. Schmidt, “Between Toy Box and Wedding Gift: Functions and Images of Athenian Pyxides,” Abbreviation: MètisMètis: Anthropologie des mondes grecs anciens 7 (2009): 111–30. When pyxides and other boxes or containers are depicted on vases, they are almost invariably associated with women and, in particular, the wedding, often serving as gifts to the bride. Nonfemale subjects occur most often on black-figure pyxides, including several with sympotic scenes attributed to the Haimon Painter or in his manner: cf. Providence 34.1374a–b (D. M. Buitron, Attic Vase Painting in New England Collections, exh. cat., Fogg Art Museum [Cambridge, MA, 1972], 66–67, no. 28; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 3198). A fragment from the lid of a pyxis from Lokroi, attributed to the workshop of Douris, preserves the only other contemporary red-figure sympotic scene on a pyxis: Kalapodi excavations K 2440 (K. Braun, “Bericht über die Keramikfunde archaischer bis hellenistischer Zeit aus dem Heiligtum bei Kalapodi,” Abbreviation: AAArchäologischer Anzeiger [1987]: 68–69, no. 22, fig. 68d–f; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 30346). It is unclear whether the Kalapodi pyxis also included female symposiasts. According to Roberts (Attic Pyxis, 178), domestic scenes begin to populate pyxides only at the beginning of the fifth century, and perhaps these early examples, with subjects related to the masculine sphere, represent a moment in production before a standard iconography was developed for the shape. Nevertheless, Princeton’s pyxis remains unusual in its combination of shape, subject, and ornament, and in the overall elaborateness of the piece, suggesting it might have been a special commission, perhaps containing a gift from a hetaira’s admiring customer.

For a corpus of frontal faces, see Y. Korshak, Frontal Faces in Attic Vase Painting of the Archaic Period (Chicago, IL, 1987). Frontisi-Ducroux (Du masque, 19–21) has argued that frontal faces could convey visual disengagement or an inability to interact with their companions. In the context of the symposion, such visual disengagement could arise from intoxication. Alternatively, the frontal face could indicate an address to the spectator, perhaps including them in the depicted action: for a recent overview of the self-reflexive nature of sympotic imagery, see R. Osborne, “Projecting Identities in the Greek Symposion,” in Material Identities, ed. J. Sofaer (Malden, 2007), 31–52. In this case the frontal woman may gesture to the owner of the pyxis, perhaps a hetaira who frequented symposia, to join in the revelry. But Frontisi-Ducroux (Du masque, 121), noting the disjunction between image and shape on Princeton’s pyxis, suggests that the painter was indifferent to the recipient of the vessel, concluding that the frontal face is erotically charged and addressed to a male symposiast. Such is most likely the case on Euphronios’s famous psykter in the Hermitage, on which occurs a similarly nude, frontally faced female banqueter: St. Petersburg B 1650 (supra). In this case, however, the shape suggests use at a symposion, with the addressee of the frontal face now likely to be a man. For a recent overview of frontal faces, with the additional argument that frontality forces the viewer to take on the role or stand in the place of an unseen internal spectator, see G. Hedreen, “Unframing the Representation: The Frontal Face in Athenian Vase-Painting,” in The Frame in Classical Art: A Cultural History, eds. V. Platt and M. Squire (Cambridge, UK, 2017), 154–87.

For the generic “ho pais kalos” inscriptions, see Princeton 1997-442 (Entry 36). The generic phrase is often interpreted within the context of male pederasty: see A. Lear and E. Cantarella, Images of Ancient Greek Pederasty: Boys Were Their Gods (London, 2008), 150–58. The inscription is thus unusual for a vessel associated with women and rarely occurs on the shape, furthering the disjunction between image and support. Several pyxides bear “kale” inscriptions accompanying domestic scenes, perhaps referring to a depicted figure or addressed to the owner of the box: e.g., by the Penthesilea Painter, Athens, Acr. 2.569 (Abbreviation: ARV2J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963 890.172; Abbreviation: BAPDBeazley Archive Pottery Database. http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk 211735).